CAMILO RESTREPO (born 1973, Medellín, Colombia), earned a masters degree in aesthetics from the National University of Colombia (2008) before going to CalArts, Los Angeles to earn an MFA (2013). He has had solo or two-person exhibitions at Sala de Arte Suramericana, Medellín (2019), Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019), and the Lux Art Institute, San Diego (2016). Group exhibitions include Centro Colombo Americano, Bogotá (2019), Museo de Arte de Pereira, Pereira (2019), Fundación Gilberto Alzate Avendaño, Bogotá (2019), Another Space, New York (2018), and Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2018). Restrepo was a recipient of the Fulbright Grant and was nominated for the Premio Luis Caballero, the most important prize in Colombia for artists over 35.

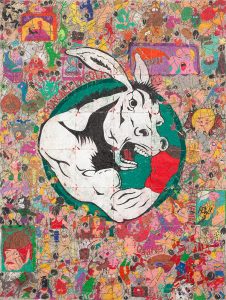

Tight Rope #10 (Diablo Rojo) is one of thirteen drawings in Restrepo's series called Tight Rope. The first nine are from 2015 and were presented in his solo exhibition of the same name at Steve Turner Los Angeles. The last four were created in 2016 for his solo exhibition at Art Brussels.

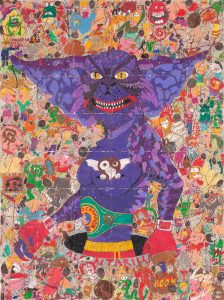

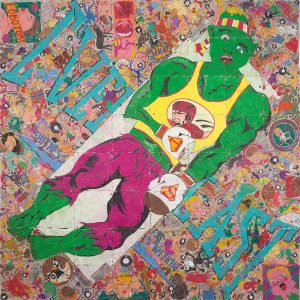

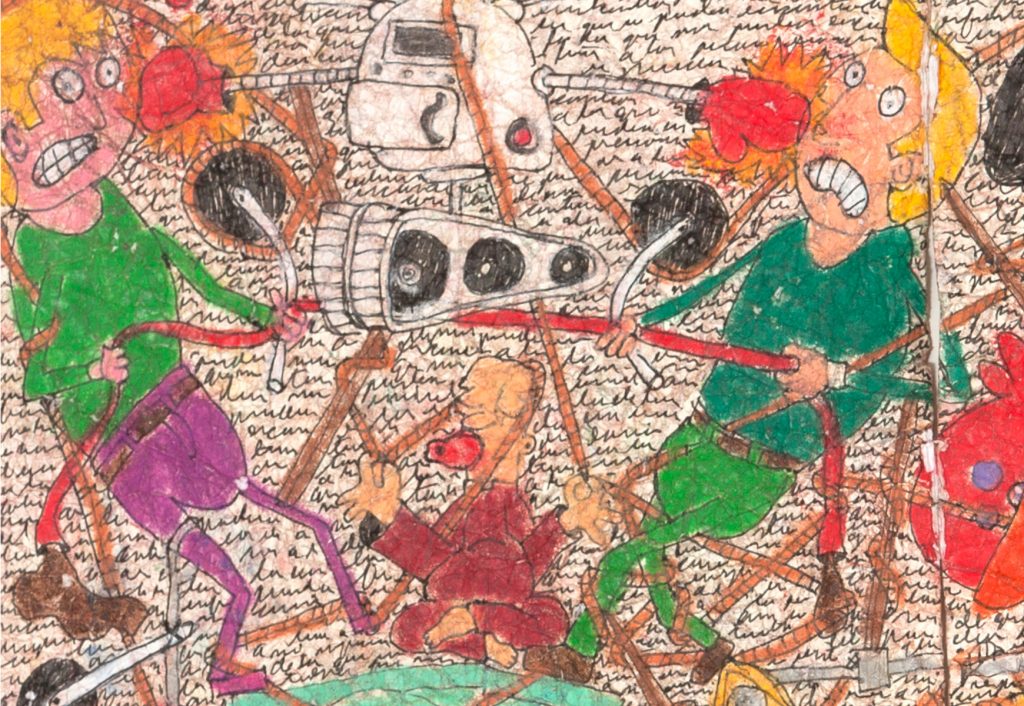

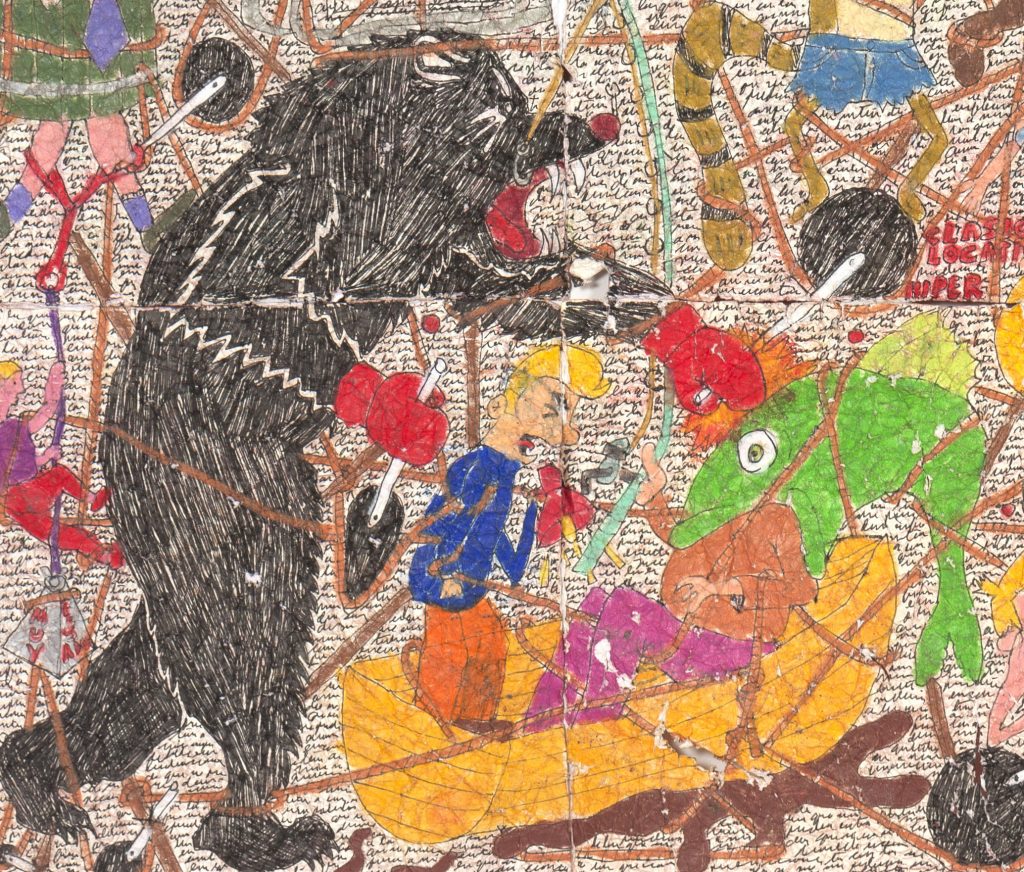

Each drawing features a boxer whose gloves reveal a lobotomized brain and a single long rope that entangles every figure throughout the drawing. This rope also wraps around pulleys that are being operated by cartoon characters that are involved in fights and other violent situations. There also are large swaths of nonsensical handwritten text. According to Restrepo, the series highlights the uncontrollable, repetitive psychic battles that occur inside the heads of obsessive people as well as the destructive, real-world combat created by the drug wars in Colombia.

Camilo Restrepo

Tight Rope #10 (Diablo Rojo), 2016

Ink, water-soluble wax pastel, tape and saliva on paper

63 x 48 inches (160 x 121.9 cm)

$18,500

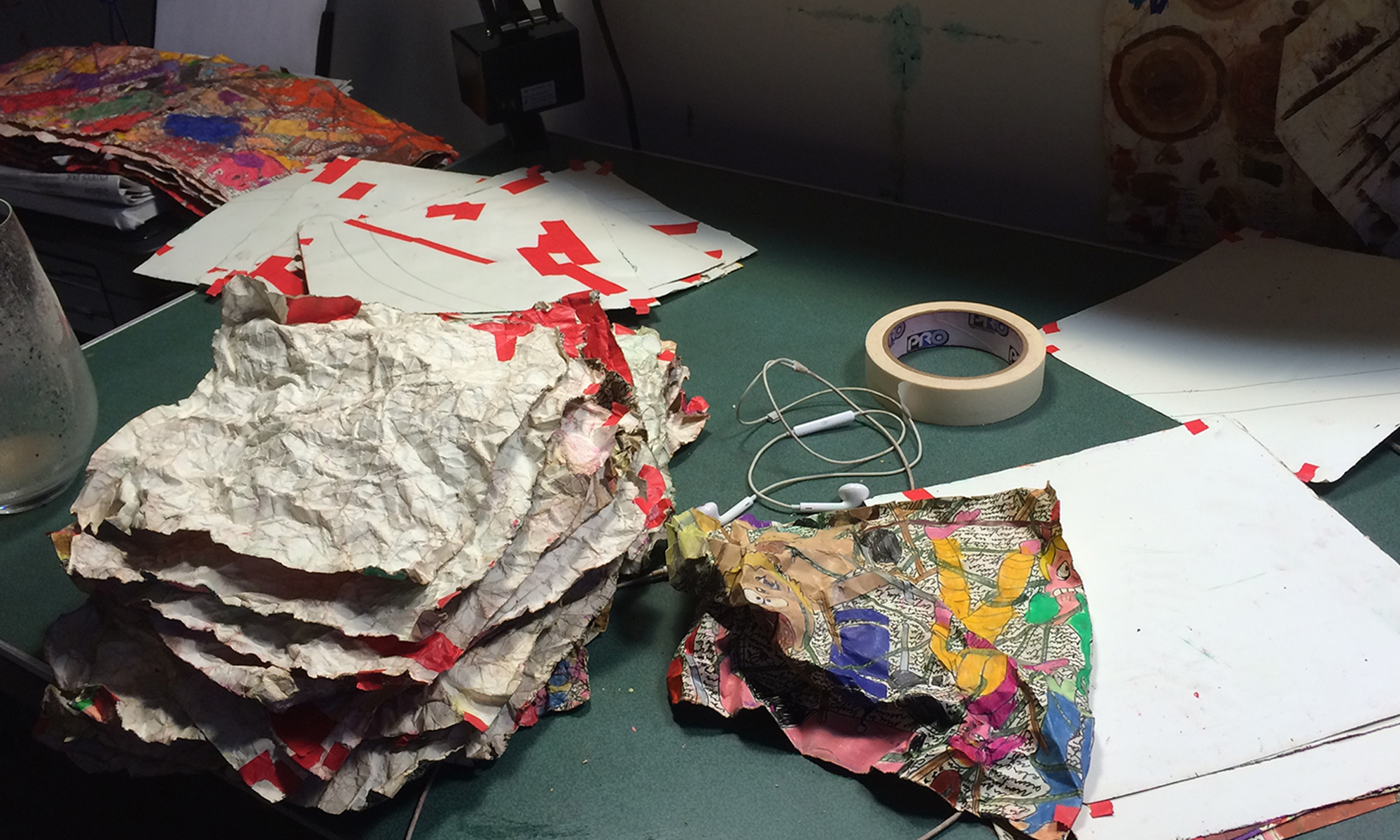

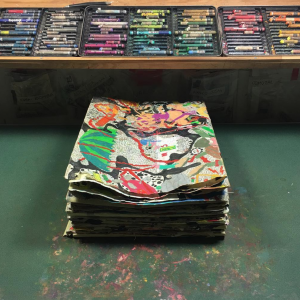

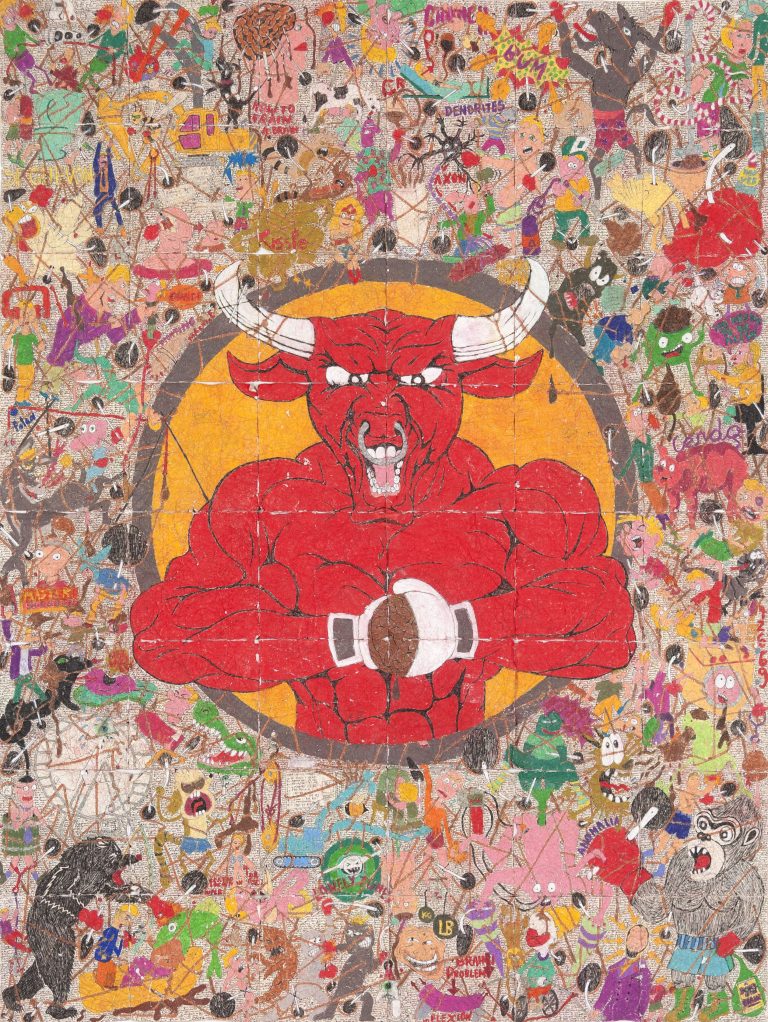

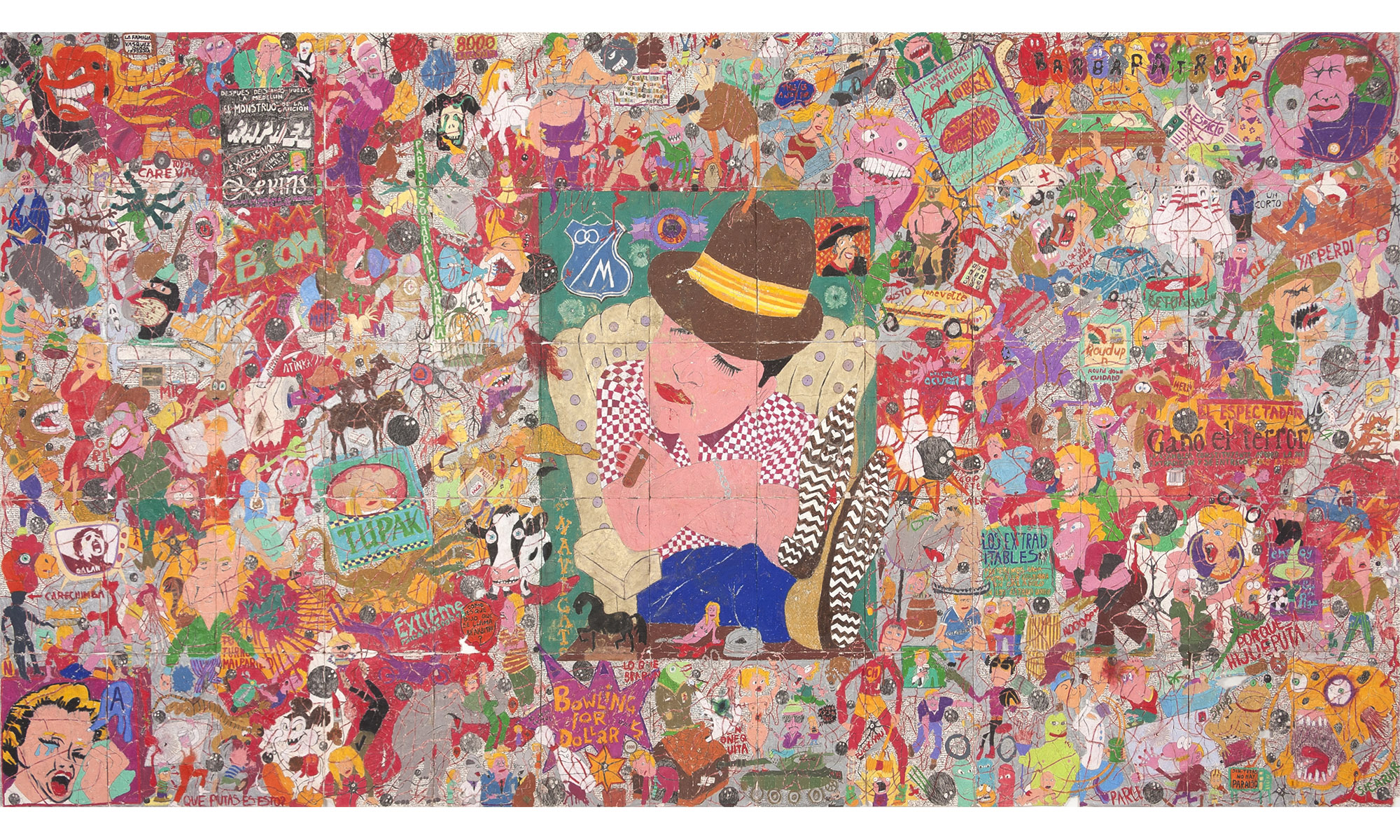

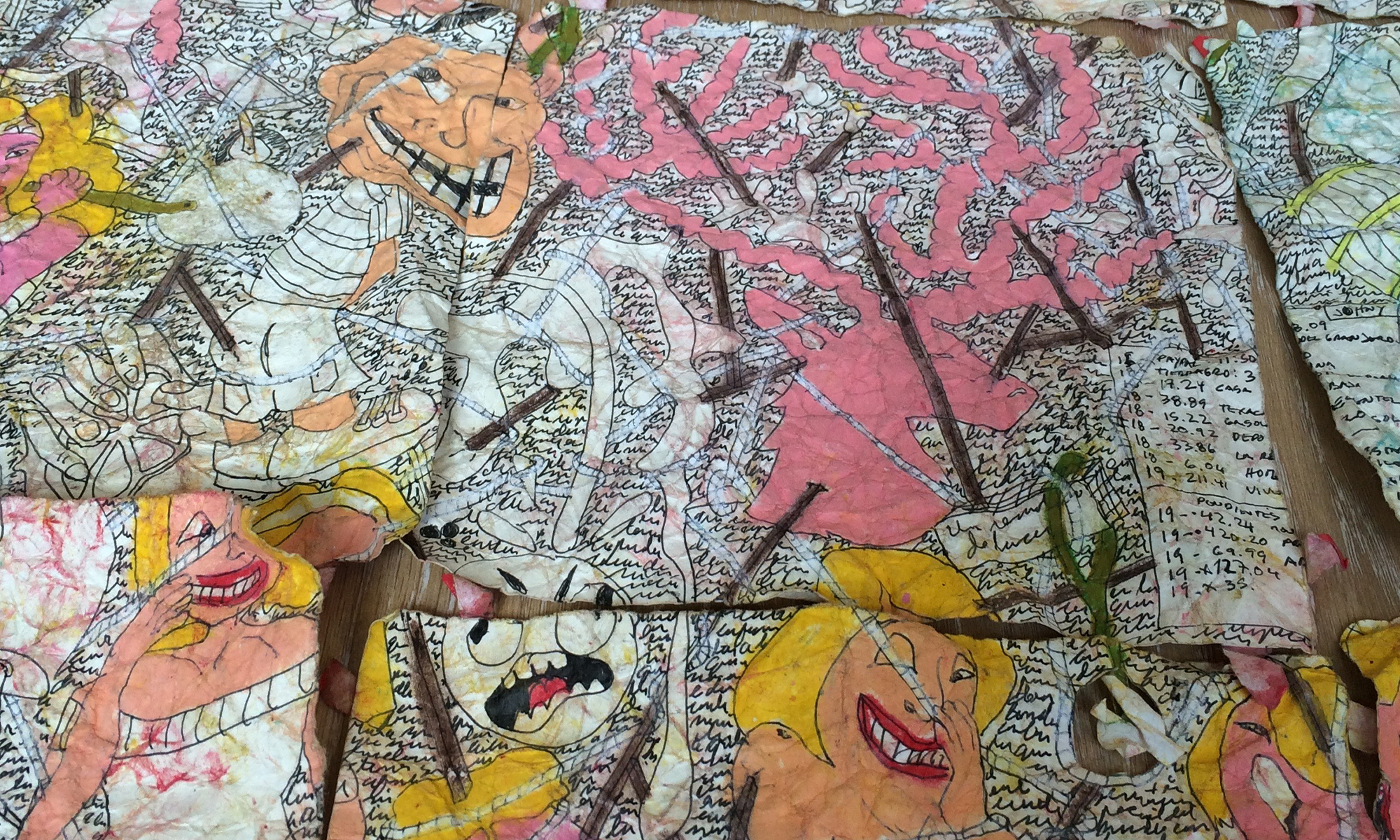

Restrepo's process includes three important stages. In the first, he makes a line drawing in ink that he then fills in with color by drawing with water-soluble pastels and by collaging newspaper clippings. Once done, he extensively damages the work. The method of destruction varies from series to series. In some, he sprays water at high pressure onto the drawing until it breaks apart and its colors run. In others, he sprays water onto the drawing and then walks on in the street so that it absorbs the texture of the pavement. In so doing the work gets degraded and takes on the marks of the street.

In the Tight Rope series, he destroyed the work by balling up the sheets very tightly, over and over and over again. This destroyed the structural integrity of the paper making it feel like a cotton bed sheet more than a piece of archival paper. Whatever the method of destruction, he significantly damages the works. The final stage is restoration of the damaged work. He mends tears and losses with hundreds, sometimes thousands of pieces of archival tape and paper patches and then reworks the damaged areas. The resulting work bears the scars of his process and the scars of his life in Medellín during the darkest days of the Pablo Escobar era.

Camilo Restrepo in conversation with Steve Turner

Steve Turner:

You were born in Medellín and have lived there most of your life. Since most people associate Colombia and especially Medellín with drug cartels and Pablo Escobar, can you describe some memorable episodes that influenced your artistic practice.

Camilo Restrepo:

The narco-violence of the ‘80s and ‘90s had a big emotional impact on me and it is very present in my work. I encountered lots of corpses during those years, the first instance was on Halloween when I was six years old. I was in a car with other kids in costume on the way to school. There was a dead man lying on the street and the driver made us get out of the car to look at him. All of us kids were wearing costume. It was a bizarre scene–there was a dead man surrounded by superheroes that could not resuscitate him. I definitely think of this scene as I create my drawings. I saw people being killed in front of me on four separate occasions. I was twelve years old the first time; the last time I saw was a man killed by a sicario (hitman) while he was playing billiards at the table next to mine. The windows of our house were blown out on three separate occasions when bombs were exploded in terrorist actions targeted at Pablo Escobar. For six months a sicario wanted to kill me because of a problem we had in a bar. He chased me a couple of times, but luckily someone killed him first. My best friend was kidnapped by the FARC guerrilla group when we were driving together to the coast for holidays. That easily could have been me. It was hard to go out knowing that you might not make it back home. Yes, the Medellín of my youth is very much in my work.

Detail from Bowling for Medellín 3, 2016

Detail from Bowling for Medellín 3, 2016

"I saw people being killed in front of me on four separate occasions. I was twelve years old the first time; the last time I saw was a man killed by a sicario (hitman) while he was playing billiards at the table next to mine. "

ST:

Why did you decide at age 38 to leave the comforts of Medellín to go to CalArts?

CR:

Because I wanted to join an artistic community where I could discuss and reconsider my ideas about art with critical peers and faculty. In Colombia, my art practice had been a lonely one as I didn't study fine arts and had mostly worked as a self-taught artist.

ST:

Did you find such an artistic community there?

CR:

Yes, I did. Most of us lived in the studios or at least spent lots of time there. It was the ideal situation. I was surrounded by people eager to talk about art. The fact that CalArts is one hour away from Los Angeles also caused us to spend more time on campus.

ST:

What did you previously study in Colombia? How did you end up making such strong conceptual work without a formal art education?

CR:

I studied mechanical engineering and then earned a masters degree in aesthetics before going to CalArts. My first works were photographs. After a while, I realized that photography was not a merely a matter of composition and color and that it had a history which was connected to conceptual art. I started to read a lot and then began my formal study of aesthetics. The curriculum was oriented more toward critical \ so my practice at the time had a strong theoretical influence. However, when it came to making art, I had very little critique of producing images and objects, I invented my self the ways to do so.

ST:

At CalArts you radically departed from your past works which were pristine photographs by starting to make the very messy drawings for which you are now well known.

Did you have any experience in drawing?

CR:

I did not. At CalArts I went through a radical two year experience that totally changed my life and my art practice. Drawing without knowing how to draw was a manifestation of my new desire to live an imperfect life. In the past, I was driven to achieve perfection. At CalArts, I learned to embrace uncertainty, to accept mistakes and to deal with the unknown.

ST:

And so you have, with very good results.

"At CalArts I went through a radical two year experience that totally changed my life and my art practice. Drawing without knowing how to draw was a manifestation of my new desire to live an imperfect life...I learned to embrace uncertainty, to accept mistakes and to deal with the unknown."

"They relate to obsessive thinking and feelings of inadequacy. Each drawing has a central character who wears boxing gloves that have been trepanned revealing a brown brain. The more he fights obsession, the more brain damage he will suffer."

ST:

Over the nearly ten years during which you have been making drawings, you have created a number of different series: Bodies of Evidence, A Land Reform, Los Caprichos, Rip Currents, Bowling for Medelín, Tight Rope, El Bloc Del Narco, etc. While each series has its own idiosyncrasies, what unites these different bodies of work?

CR:

First, the materiality and the process of making the drawings. I draw with a pen, for example. It means that if I want to erase something, I must use a scalpel to do so, a process that leaves the paper scarred. I also work in a way that produces an overall dirty quality. As I draw with water-soluble wax pastels on small sheets of paper that are taped together, I am constantly folding and unfolding the paper to work on a single sheet. In so doing, when I am working on one sheet, every sheet below it is being affected. New marks appear without any specific intention. As I partially destroy and reconstruct the finished drawings, they also carry the many marks of that process, all of which makes the paper an important element beyond that of a neat and invisible surface.

Second is my use of cartoon-like imagery in all the series. As I have no academic drawing skills, I rely on the Internet for source images, and the images that are must useful to me are cartoon images. I find it easier draw a cartoon character than a photograph of a person. I also think that viewers relate to them more easily and that enables me to address more serious subjects in a light-hearted way.

Third, all the series relate to my life experience and thus convey the suffering in my own head as well as the larger societal suffering caused by the war on drugs. They all criticize two utopias of perfection: the utopia of the perfect individual and the utopia of a world free of drugs.

ST:

Can you briefly describe your motivations in the Tight Rope series?

CR:

They relate to obsessive thinking and feelings of inadequacy. Each drawing has a central character who wears boxing gloves that have been trepanned revealing a brown brain. The more he fights obsession, the more brain damage he will suffer. The series title relates to the rope that runs through the entire drawing. It has no beginning and no end and it entangles every image surrounding the main character. It goes through a system of pulleys that also are everywhere in the drawing. This all is meant to represent an insane mechanism – the brain, with numerous fights between cartoon characters, with the brain depicted as a digestive system full of shit.

When I finished the drawing, I separated all the component sheets them so that I could tightly crumple and un-crumple each several times. This caused the paper appears to be tired and listless. I then taped them all together again as a final step. This process also represents the repetitive and obsessive fights that can occur inside one’s head.

ST:

From our many conversations, I know that every minute detail in your works is there for a reason. Can you elaborate on some specific passages in Tight Rope #10 (Diablo Rojo)?

CR:

The central character is a red bull that appears to be strong and defiant. This represents the armor that we build to prevent people from seeing that we are struggling inside and are some times devastated. By the way, Diablo Rojo (red devil) is a very popular product in Colombia which is used to clear obstructions in the sewer lines.

CR:

This specific detail shows a never-ending tug of war game between two people, who are at the same time being hit in the face by a robot. Both ends of the rope leak a brown liquid. This relates to the automatic modes that govern our minds, something akin to never-

ending rumination. The unreadable automatic handwriting is meant to reinforce the idea of useless rumination. Finally there is Homer Simpson meditating below the guys that are fighting. I have been meditating for several years and that is a practice that has helped me to lessen suffering by allowing me not to identify with my thoughts.

ST:

What about this one?

CR:

In this image there is a word in spanish: ANOMALIA. An anomaly is a deviation from the general rule or a fault, a defect. This is how consider myself for my entire life before the process I went through at CalArts. There is also a big monkey which relates to the monkey mind, which is a Buddhist term that means a mind that is restless and unsettled. Even though we all experience these mental states, the monkey becomes a gorilla in a person diagnosed with general anxiety disorder.

ST:

And this one?

CR:

At the far left, there is a guy trying to climb the back of a monster. That might seem like a good way to defeat the monster, but look below. He is carrying a weight that makes his mission impossible. My working process embraces incongruity. Here you can see a fishing boat stuck in a brown puddle, a fisherman being eaten by the fish he was trying to catch, a fish hook in the mouth of a bear who is wearing boxing gloves and is punching the fisherman through the fish that is eating his head. There also is another man in the boat who is shouting instructions with a megaphone to no avail. Everything is a mess. Black monsters and green fish were common in my childhood dreams. Note also the hole in the paper caused by the crumpling and un-crumpling of the individual sheets.

Please direct inquiries to:

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la