Hannah Wilson in conversation with Steve Turner, December 2024

Steve Turner:

This conversation is long overdue. Your solo show, Number One Fan, was presented in April and May of this year, and it remains vivid in my memory. I suppose I never wanted it to end as two of the paintings are still hanging in my office. Before we discuss your show and your painting practice in general, I would love to find out more about your past. Can you describe your life growing up in England?

Hannah Wilson:

I was born in Milton Keynes which is somewhat of an infamous location in the UK. It’s a new town, an hour outside of London which was founded in 1967 as a sort of modern utopia. It’s a strange place because it was built on a grid system, similar to Los Angeles, and all of the trees are planted in perfectly straight lines. Growing up it felt like there wasn’t much to do on the weekends. My friends and I would walk in circles around the giant shopping center and see whatever was on at the cinema. It felt like we were killing time, but I’m sure that’s where my love of film began. To this day I will watch anything at least once.

I was always drawing, and looking back now, I can see the connection to my current practice. As a teenager I would lovingly render portraits of my favorite male celebrities with color pencil. I’m extremely lucky that my parents supported me in my chosen path and that they never pressured me to go into a more normal career. When I was young they took me to MK Gallery in Milton Keynes which is where I saw my first exhibition, and later my Dad and I would go on trips to London to visit the Tate. Most of my family work for the National Health Service so I’m in a very different field, but to say I’m the only creative one would be a stretch. I have an older sister who loved to act when she was at university and my Dad has been making elaborately decorated cakes for as long as I can remember! We all have our own talent.

ST:

Did you go to University right after high school? Where did you go and what did you study?

HW:

Rather than completing A-Levels at high school to get into University, when I was 16, I applied to a two year Art & Design course at Northampton College. It was a big change, I had to travel two hours in and two hours back every day, but it was worth it because I knew it was what I wanted. In the first year, we covered a bit of everything, but in the second year, I had free reign to do what I wanted, and it was then that I first started to paint. It totally opened up my world, I didn’t even know Fine Art was something you could study at University. I wanted to apply to the London schools but was uncertain if it was worth trying, and I remember a tutor named Emma who believed in me and pushed me to apply. To this day, I’m so grateful to her. I took a chance and I ended up getting accepted to study Fine Art at Goldsmiths which was my dream school.

When I arrived at Goldsmiths it was a big change, I’m a shy person and so it took me a little while to settle in and feel at ease in the environment. At the time nobody at Goldsmiths was really painting, so during the first term, I did photography. It's a funny story. I was taking staged self-portraits in which I was wearing wigs but I had never heard of Cindy Sherman! My tutor could see that my heart wasn’t in it and took me aside and said, it’s clear you want to paint so why don’t you just do it? I took her advice and from there I was off and running. What I liked about Goldsmiths was they left you to your own devices, and so I was able to really push myself and try a million things to figure out what worked. Outside of the campus, the proximity to museums and galleries meant that I spent most of my spare time going to shows and soaking up everything I possibly could. It was a massively generative time, it shaped so much of who I am today as an artist and a person.

ST:

What were the subjects of your earliest paintings? And, were there any museum or gallery exhibitions that were especially influential? What else about London was so influential?

HW:

The earliest paintings were from photographs. The first proper painting I did outside of school was when I was around fifteen years old. It was a portrait of Francis Bacon, who was, and still is, one of my favorite artists. When I was on my college course I painted a portrait of my Dad. It went on like that for a while with most of my portraits of family members. As an exercise for myself in my first year at Goldsmiths I would do paintings of my Mum over and over again from the same photograph, but with a time limit of ten minutes for each painting. It was meant to free up my process.

In terms of exhibitions, the show Body Language at the Saatchi Gallery in 2013 was massively influential. I had never seen figurative painting like that, messy and cartoon-like but still all about the paint. That show was the reason why I began imposing these limits, I was eager to step outside of myself and try to paint in a way that felt physical and urgent. I knew the only way to access it was to make it impossible for me to hesitate. In those ten minutes there was no time to think, only for my hand to move and make the picture. With this same technique I moved onto working from photos in magazines, inspired by Chantal Joffe’s series of A5 sized paintings I saw in Body Language, and then to women from my imagination which was the source of my subject matter for a good few years after that. While I was at Goldsmiths I also saw the Marlene Dumas exhibition, The Image as Burden at the Tate Modern six times, and did the same with Agnes Martin’s retrospective the same year. I love retrospectives, I have always felt drawn to shows by people who have had the drive to paint their whole lives as it’s an experience I plan to share.

Other than exhibitions, London itself was very impactful. It’s a very pedestrian friendly city so I would walk everywhere. When necessary, I would take the bus rather than the tube so I could observe the world through the window. The act of looking and of noticing small details in the city was very inspiring.

ST:

You came along at a time when figurative painting was highly popular, but I find it interesting that you were so taken with Agnes Martin’s retrospective. What especially impressed you about this exhibition?

HW:

Martin’s retrospective was the first time I saw her work. I was so struck by the raw power of the paintings. They thrummed with energy. In spite of the way they are lightly treated with color and application of material, they hold such immense weight. I find myself getting lost in small moments of imperfection. To me, her work is all about the human hand. Her lines wobble and color creeps over segmented lines. It could only be a human body that made these paintings and when I look at them I feel her presence so strongly. I became overwhelmed with emotion when I saw the works from her later years, those with grids for which she is best known. It was not from anticipation as these were entirely new to me. Such a strong reaction is uncommon in my experience, so I find myself wanting to dig deeper and close the gap.

It’s the same to this day. Her paintings continue to move me a lot, so whenever I see one, I always spend a lot of time with it. Her work reminds me that you can pack a big punch by doing just enough on the canvas if you work with intention. I also love how she speaks about art-making. When I was in my MFA program, I wrote a paper on Martin’s methodology as it related to mine. Her statement that an artist is “one who can fail and fail and still go on” deeply resonates with me.

ST:

Let’s get back to your work. A couple of years ago, you created quite a few paintings that depicted Adam Sandler as he appeared in his films. What motivated this development in your studio practice?

HW:

It was a coincidence, as are most new directions in my practice. I go through stages of being enamored with different film directors. When I was doing a deep dive into the films of Paul Thomas Anderson. I watched Punch Drunk Love for the first time and was massively drawn to Sandler’s character Barry Egan. I made a series of paintings from the film for my degree show, and have made more paintings since then. I still want to paint more from that film. My love of Barry, a character who is often overwhelmed by his own emotions, led me to watch more and more Adam Sandler films. Punch Drunk Love seems to feature a more serious version of the role he typically plays, but I find that each of his characters has a moment where something snaps and there is an outburst of some kind.

In depicting his character’s outbursts, I believe I am led to address comparable overwhelming moments or crippling insecurity in my life. When I was a teenager I would project myself onto characters in films or in books and they would become vessels for me to explore different facets of myself. I often joke that Adam Sandler is more of an idea than a person in my practice, but it’s more likely that he is a stand-in for me. I have moved on to other characters for now, but if I revisit him, I think I would like it to be the focus of an entire exhibition.

ST:

You mentioned that you created paintings based on photographs from magazines as well as from your imagination. Since you so dramatically simplify and stylize the subjects in your paintings, is there much difference? It seems you have always imagined something that is different from a photo-realist representation. In doing so, I wonder if Guston’s paintings are especially inspiring.

HW:

That’s a good question to think about. I think you’re right, there isn’t much difference, at least for the viewer. In terms of context and what drives the work, it is important, but you’re right that in terms of style the outcome would be much the same. It’s interesting that you mention Guston in relation to this. I was just watching (or should I say re-watching) the documentary Conversations with Philip Guston in the studio this week, and he speaks about this very thing. He said that he is always asked why he paints in his signature style, as if he had any choice in the matter. He goes on to say that all he wants to do is to “paint and not die”. That’s how I feel too, I have always painted and I have always painted the same way. Even before intending to work more loosely, my work always has had this simplified quality, even if I endeavored to make it not so. I would be lying if I said I have always been content with this element of my work. I now accept that this is at the core of my visual language.

I find Guston to be inspiring in many ways. In terms of style, what I admire most is how his works have a cartoonish quality but are still grounded in the material. They feel, for lack of a better word, serious. They never feel flat, like you could just go and peel them off the wall. This same quality is what I strive for in my work, simplified in one way but still weighty. Guston gives me great confidence to let things be simple. If I added more detail or tried to make them more realistic they wouldn’t be any better. And by better, I mean that they wouldn’t articulate what I want to say with any more specificity. If anything they would feel more muddled.

ST:

And just what is it that you want them to say?

HW:

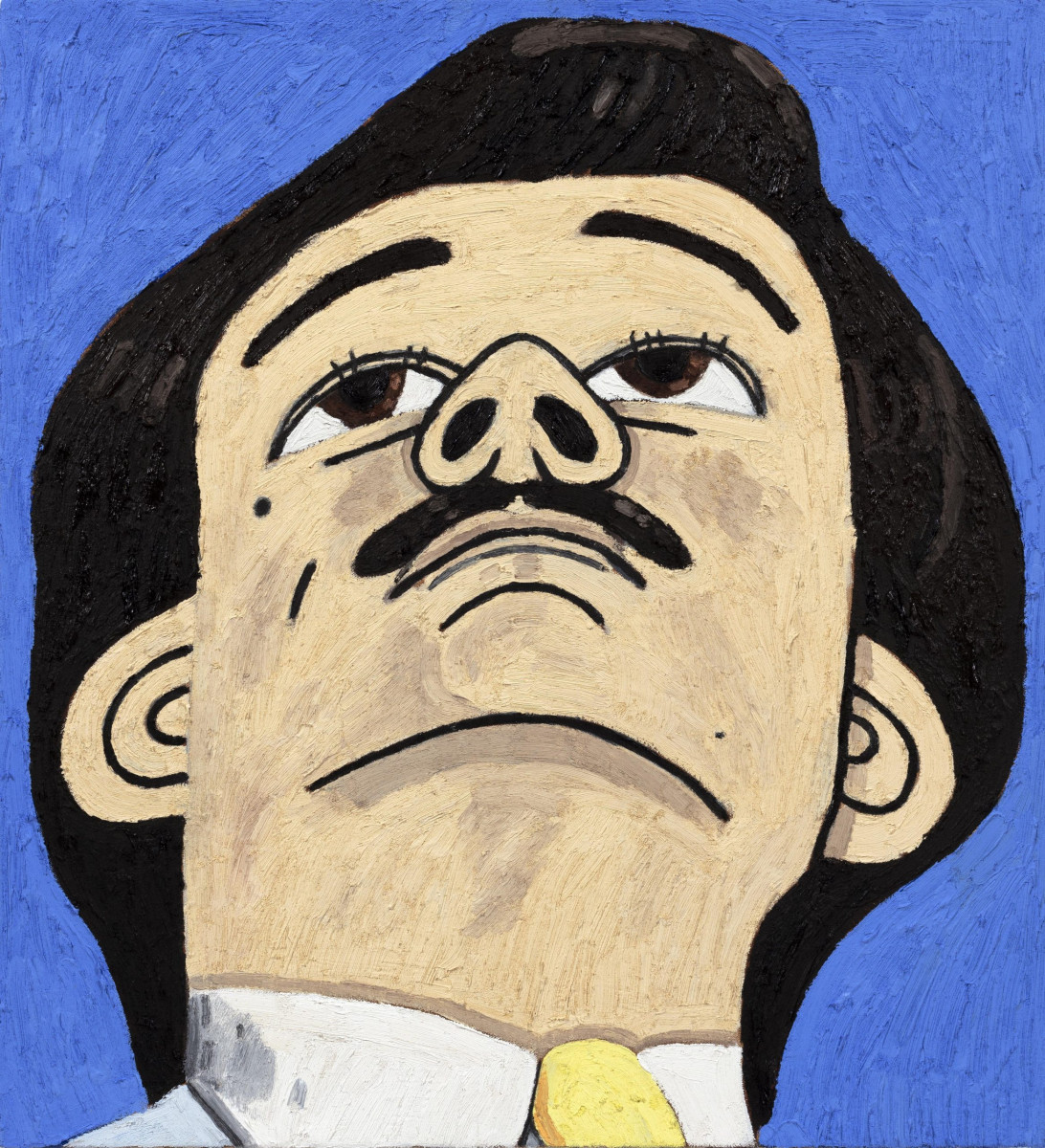

That always is evolving. The work is an extension of myself, so the motivation changes from show to show. In anticipation of Number One Fan I was grappling with my deep desire to have a career as an artist. To channel that, I projected myself onto Rupert Pupkin, the Robert DeNiro character from the 1982 Martin Scorsese film, The King of Comedy. From my knowledge of film history, Pupkin is a totally singular character. I don’t know of any other characters who have his audacity and patience. Unlike Sandler’s Barry Egan who becomes overwhelmed and might occasionally erupt with violence, Pupkin remains undeterred to the point of sheer idiocy. This is clear from the very first scene where he managed to cajole his way into the back seat of a limo for an audience with Jerry Langford, the late night talk show host and Rupert’s idol, played by Jerry Lewis. The key word here is audience. It is clear that Pupkin has been rehearsing for this moment his whole life, and anything Langford says that doesn’t fit into his script falls on deaf ears. It’s horribly cringey to watch, and this theme continues for two more hours!

Pupkin lives his life in this cycle of performance and rehearsal which greatly interests me. It mirrors my experience as I pursue a career as a professional artist where one must appear unflappable in the face of constant rejection and never let doubt creep in. Pupkin however, is entirely lacking in self-doubt or introspection. As such, I had to portray him as an island, someone totally impenetrable. In doing so, I am asking myself what lengths I would be willing to go to to achieve that. I would never go as far as Pupkin, but his urgency is a quality I recognise in myself and I want to pose the same question to the viewer. This feels especially pertinent in the wake of the recent U.S. election where blind individualism seems to be a common theme.

No matter the starting point for a work or series, I always try to portray the human condition and the anxieties that come with it. Over the last year I feel that I have used my painting practice to reposition myself within the surrounding world.

ST:

For Number One Fan, you also created some fabulous paintings of Jerry Langford. What motivated you to paint this character? I also wonder why you did not create any paintings of the other most memorable character of Masha played by Sandra Bernhard.

HW:

Jerry Langford is the exact opposite of Rupert Pupkin. He, like Jerry Lewis, is larger than life in the eyes of the public. Where I thought of Pupkin as an island, I thought of Langford as a mountain. The largest painting in the exhibition shows him in a moment of reflection with his head in his hands. Pupkin pushes, and Langford bends until he finally snaps. His persona leads you to believe he is untouchable, but he is easily disturbed and influenced. I also wanted to paint these two characters for the way they dressed. Pupkin’s simperingly-toned collection of suits is clearly a poor imitation of Langford’s smart wardrobe. There’s a real sadness in this for I realized that Pupkin would only ever be a poor imitation of the real thing, I suppose a cautionary tale for any aspiring artist.

As for Masha, she is a brilliant character but I can’t say I had any urge to paint her. I am currently more drawn to depicting isolated male figures, but I also felt that I had little to say about Masha as she is so self-sufficient. I also thought a lot about gender in the way that the two Jerry fanatics, Masha and Rupert, got treated. Masha is consistently knocked back and ridiculed while Rupert is allowed to get ridiculously far in spite of his behavior.

ST:

Beyond these general motivations and your composition, line and color, I find that the surface of your recent paintings to be especially alluring. Two of your paintings are now hanging in my office. When light streams in from the skylight I can become transfixed by the effect of the light on your textured surface. Every brush stroke has added drama and I love when you suddenly change the directional brush work within a single block of color. I see your fast hand at work. Can you elaborate on the techniques you use to bring about these effects?

HW:

Of course. I’m so glad that’s something that you notice in the work. As my compositions contain lots of solid color, the weight of the paint itself and the direction of the brush strokes are vitally important. To achieve these effects, I use a combination of techniques that I have arrived at through trial and error. For the weight of the paint itself, I use oil paints that I mix with an impasto medium. I use a specific brand that has a certain gritty quality that none of the others have. The first thing I do when starting a painting is mix the colors inasmuch as I need large quantities on the palette. As days pass, the paint becomes more viscous and develops a skin. I paint several layers to achieve the surface I want. That takes time, so when I paint the final layer, the oils have hardened to such an extent that they nearly resist the brush. This causes the paint to retain its thickness on the canvas and it makes the brush strokes more noticeable. Maybe it’s just a painter thing, but I always pay a lot of attention to the brush strokes when I look at a painting. Every mark is so important. For my own brush strokes, I rely on instinct hoping that my marks will lead a viewer to discover important details by actively looking at the entire composition.

ST:

Since Number One Fan was your largest solo show to date, I wonder what you learned by seeing your works installed in such a large room, where each painting had so much room to breathe?

HW:

It was an absolutely wonderful experience. I love exhibitions that show just enough works with lots of empty wall space between them. It took a while for me to gain the confidence to do this, but the difference this time was the sheer size of your main gallery. It was such a massive step up for me compared to the other spaces at which I had exhibited in the past. This was very exciting, but I must admit that I was worried that the works might get swallowed up by the big room. You promised me that they would not and I am very grateful for your belief in me and my works and your reassurance. When I stepped into the gallery, I was so thrilled. The installation was absolutely perfect and there was no need for even one more painting. Rupert Pupkin and Jerry Langford owned the room and I am so happy that I was able to make it out to Los Angeles to see the show in person. The experience was incredibly empowering and it has buoyed me as I move forward in my practice. I am increasingly comfortable expressing that I am proud of myself, something I learned working on this show, and I feel less vulnerable to nervousness and doubt.

ST:

I also wonder how you liked your experience of being in Los Angeles, the film capital of the world. Was it as you expected?

HW:

Honestly, I wasn’t sure what to expect! My partner Kat and I had never been to the States, so we tried to keep ourselves open to whatever experiences came our way and take as many local recommendations as possible. It was like nowhere I had ever been before. It is worlds away from the U.K. in terms of sheer scale and the natural landscape. We did speak a lot about movies while we were out there, and we both agreed that Punch Drunk Love (which is getting a lot of air time in this conversation!) was by far the most accurate depiction of Los Angeles we had seen. It was strange to physically be somewhere that I had experienced so much on screen, but I loved that. Beyond that, there was so much local history that we were keen to explore. Kat is a long-time admirer of Los Angeles architecture, especially the vernacular buildings. One of our favorite memories is the pilgrimage we took to The Donut Hole in La Puente. I love how we would constantly come upon these landmarks which left us feeling that we had one foot in the everyday and the other in a surreal dream-world.