What To See, And Buy, At ArtBo

-Scott Indrisek

There are many good, strange things about the twelfth edition of ArtBo in Bogotá, Colombia. Leaving aside the tangled political context — i.e. how odd it feels to be focusing on an art fair in a country that’s worrying about loftier things, like how to formally end a multi-decade civil war after a collapsed peace deal — ArtBo is an exceedingly pleasant, fairly concise, and smartly curated affair. Its quirks, especially, are laudable. In place of a typically overpriced and bland concession area, ArtBo has a miniature pop-up iteration of local supermarket chain Carulla, hawking packaged meats, sushi, and canned beer at supermarket prices. “Is it an art piece?” a journo-peer inquired of the set-up, which indeed could have been a meticulous Elmgreen & Dragset trifle. But before hitting the $0.75 Club Colombia, I was over at the booth of Galerie Peter Kilchmann, who is showing several very-mixed-media works by Mexican political-conceptualist Teresa Margolles. “Wasn’t she at Frieze? You wanted to buy her work?” a woman next to me said, nudging her friend, the markety talk a little disturbing given that one of the pieces on view was made of string used in Guadalajara murder autopsies. Another set of sculptures repurposed shards of glass culled from dead bodies in Sinaloa, using them to craft gaudily ostentatious jewelry. The booth’s back wall is completely covered by Pesquisas (Inquiries), 2016, a gridded collage of photographs of missing-women posters in Cuidad Juarez.

There are many good, strange things about the twelfth edition of ArtBo in Bogotá, Colombia. Leaving aside the tangled political context — i.e. how odd it feels to be focusing on an art fair in a country that’s worrying about loftier things, like how to formally end a multi-decade civil war after a collapsed peace deal — ArtBo is an exceedingly pleasant, fairly concise, and smartly curated affair. Its quirks, especially, are laudable. In place of a typically overpriced and bland concession area, ArtBo has a miniature pop-up iteration of local supermarket chain Carulla, hawking packaged meats, sushi, and canned beer at supermarket prices. “Is it an art piece?” a journo-peer inquired of the set-up, which indeed could have been a meticulous Elmgreen & Dragset trifle. But before hitting the $0.75 Club Colombia, I was over at the booth of Galerie Peter Kilchmann, who is showing several very-mixed-media works by Mexican political-conceptualist Teresa Margolles. “Wasn’t she at Frieze? You wanted to buy her work?” a woman next to me said, nudging her friend, the markety talk a little disturbing given that one of the pieces on view was made of string used in Guadalajara murder autopsies. Another set of sculptures repurposed shards of glass culled from dead bodies in Sinaloa, using them to craft gaudily ostentatious jewelry. The booth’s back wall is completely covered by Pesquisas (Inquiries), 2016, a gridded collage of photographs of missing-women posters in Cuidad Juarez.

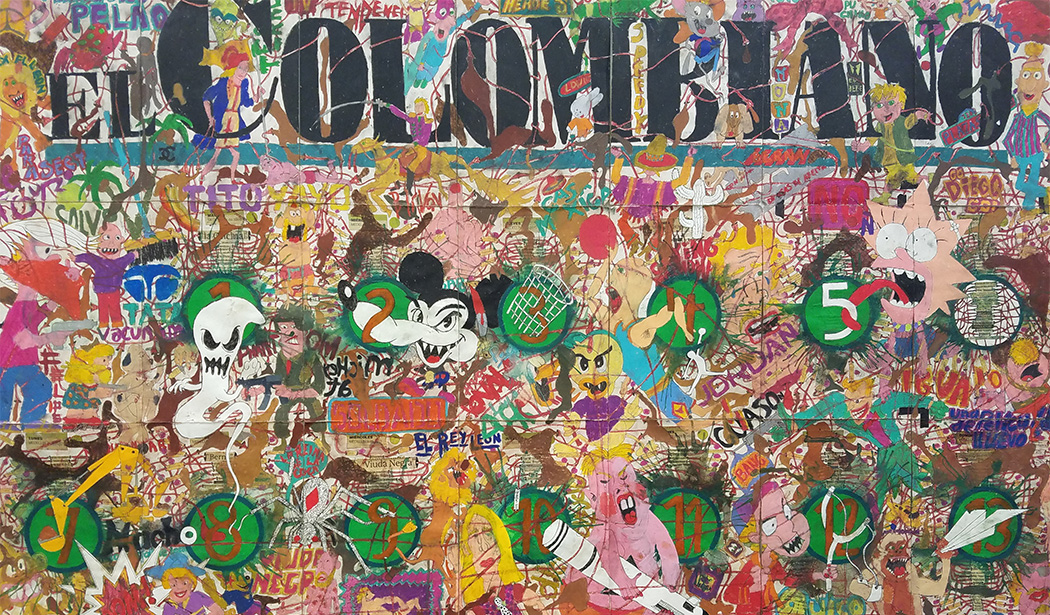

Bad news gets a more frenetic treatment over at Steve Turner gallery, which is showing a number of pieces by Medellin-born Camilo Restrepo. Any September Is A Black September Down Here #1 (El Colombiano), 2016, layers wild and dense cartoon imagery over cut-and-pasted newspaper clippings; smaller drawings have tiny baggies of faux-cocaine affixed to them. Paris gallery Mor Charpentier has works by thirty-something Mexican artist Edgar de Aragón: Printed maps, of Colombia and elsewhere, which have been drawn and collaged on. Color-coded areas delineate military bases and zones of coca production, but Aragón’s augmentations make the maps look like relics from a time of feverish and magical belief: bloated pigs, multi-headed snakes, and devils cavort over the cartography, joined by a modified version of the HSBC logo.

But don’t go thinking that everything is this heavy over at ArtBo. A jolt of sugary whimsy can be had over at El Museo, which is showing several works by Colombian sculptor Nadín Ospina — an emaciated silver extraterrestrial; a deskweight-sized piece that appropriates the three-eyed green aliens from the “Minions” movie. Y Gallery of New York has wonky, figurative acrylic-and-goldleaf paintings by Summer Wheat, done on sheets of aluminum mesh typically used for screen doors. Galería de la Oficina is selling a pair of early 90s, homoerotically charged cartoons by Álvaro Barrios. And Johannes Vogt of New York — who has also brought work by Florian Schmidt, Monika Bravo, and others — has a terrific canvas by Colombia-born, London-based Alejandro Ospina. Composed first on the computer before Ospina starts projecting, painting, and layering figurative and abstract elements, it resembles an urban street awash in a tornado of squiggling gestures, swatches of color, and stark traffic markings.

If you’re looking for something small and affordable at ArtBo, consider a series of $2200 charcoal-on-paper works by Jemma Appleby, shown by Lamb Arts of London. They’re quiet studies, all light and shadow and reflection, of the interiors of various museums, most of which the artist has not personally visited. If you’re looking for something small and not at all affordable, consider one of the tiny Wilson Díaz canvases being shown by Instituto de Visión in a portion of ArtBo curated by Jens Hoffman. They range in mood and tone — some Luc Tuymanesque, hazy photorealistic depictions of politicians, or of the artist’s own past performances, joined by cartoon mosquitos, cavemen, and other eclectic snippets. They’re a sort of memory-retrospective, an Instituto rep told me, a way for Díaz to pause and reflect on shared historical touchstones and visual noise alike: “a Colombian life.”