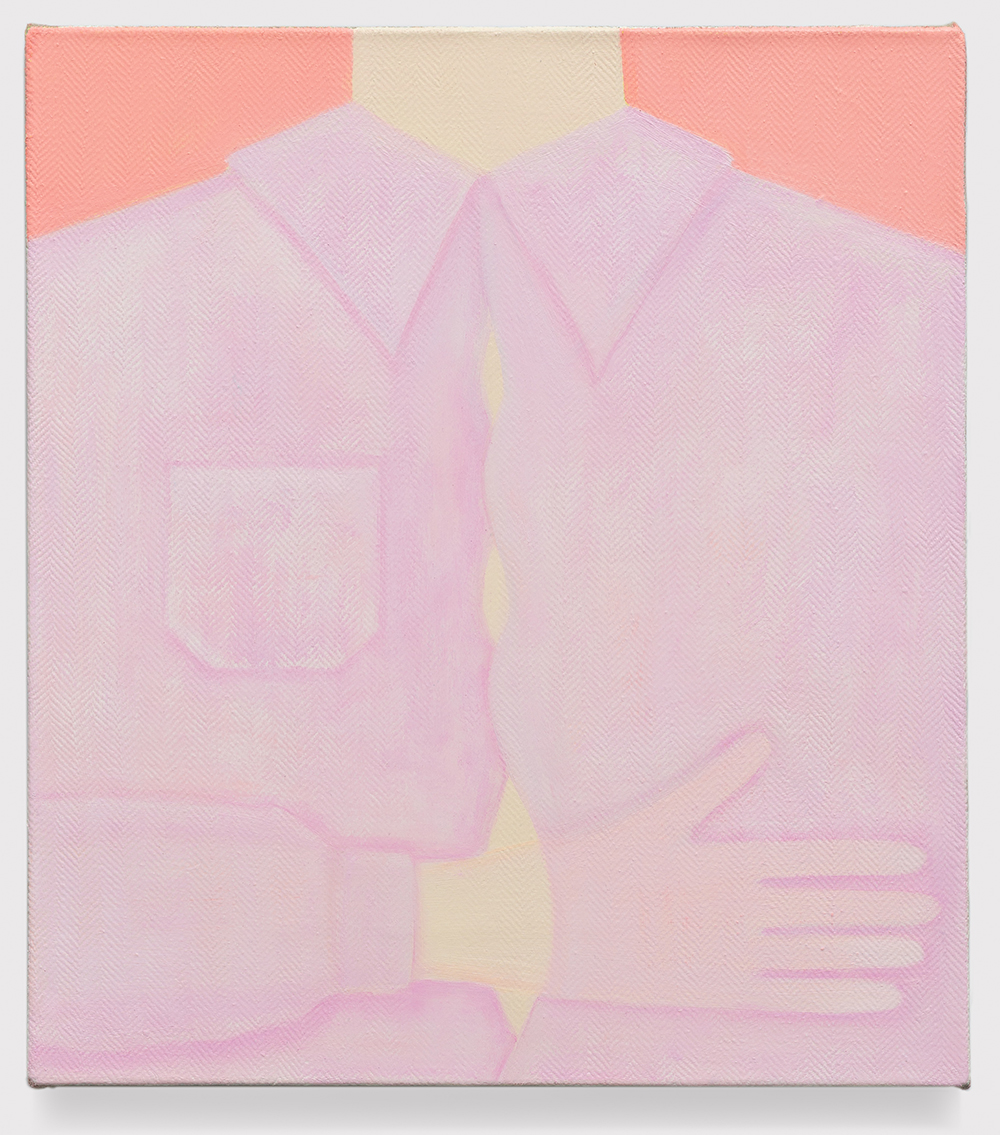

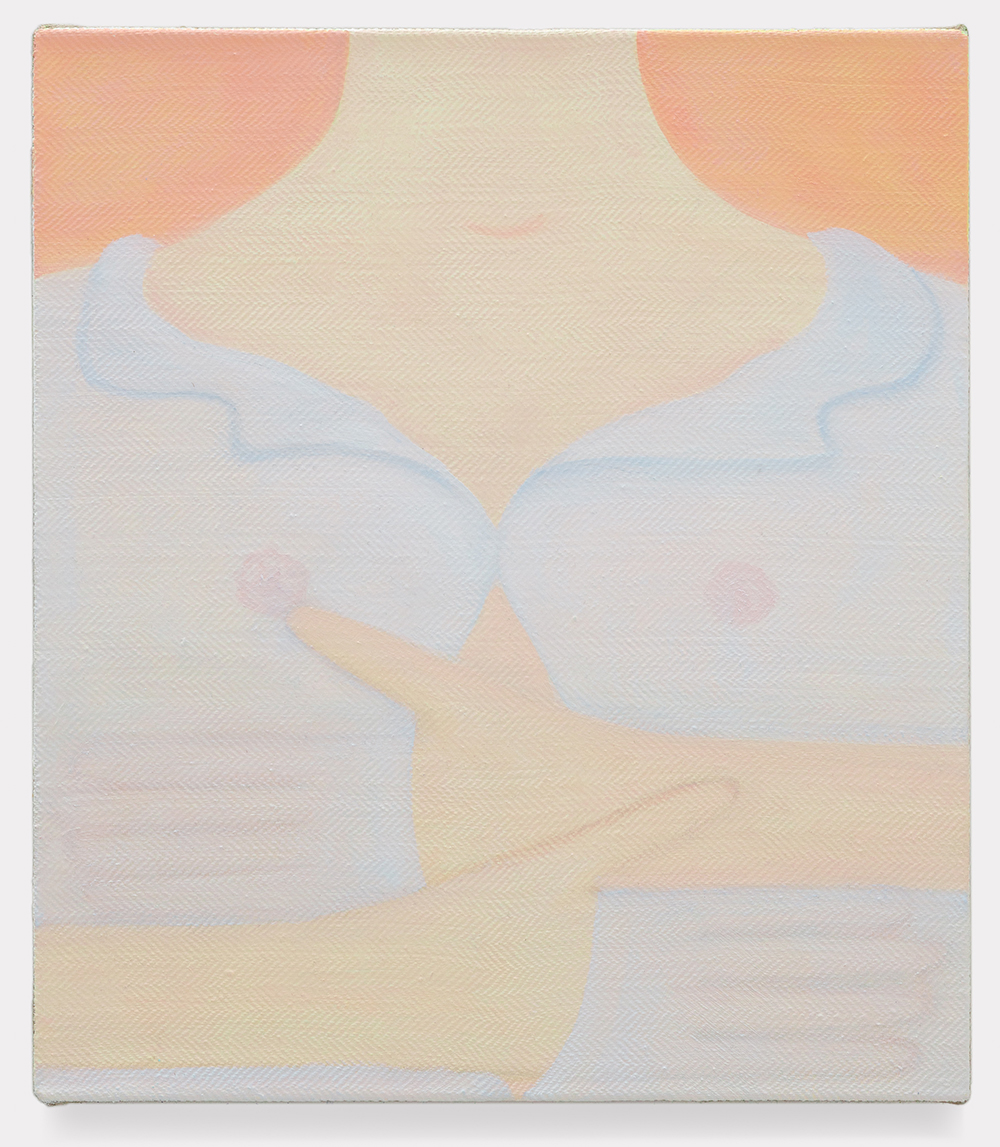

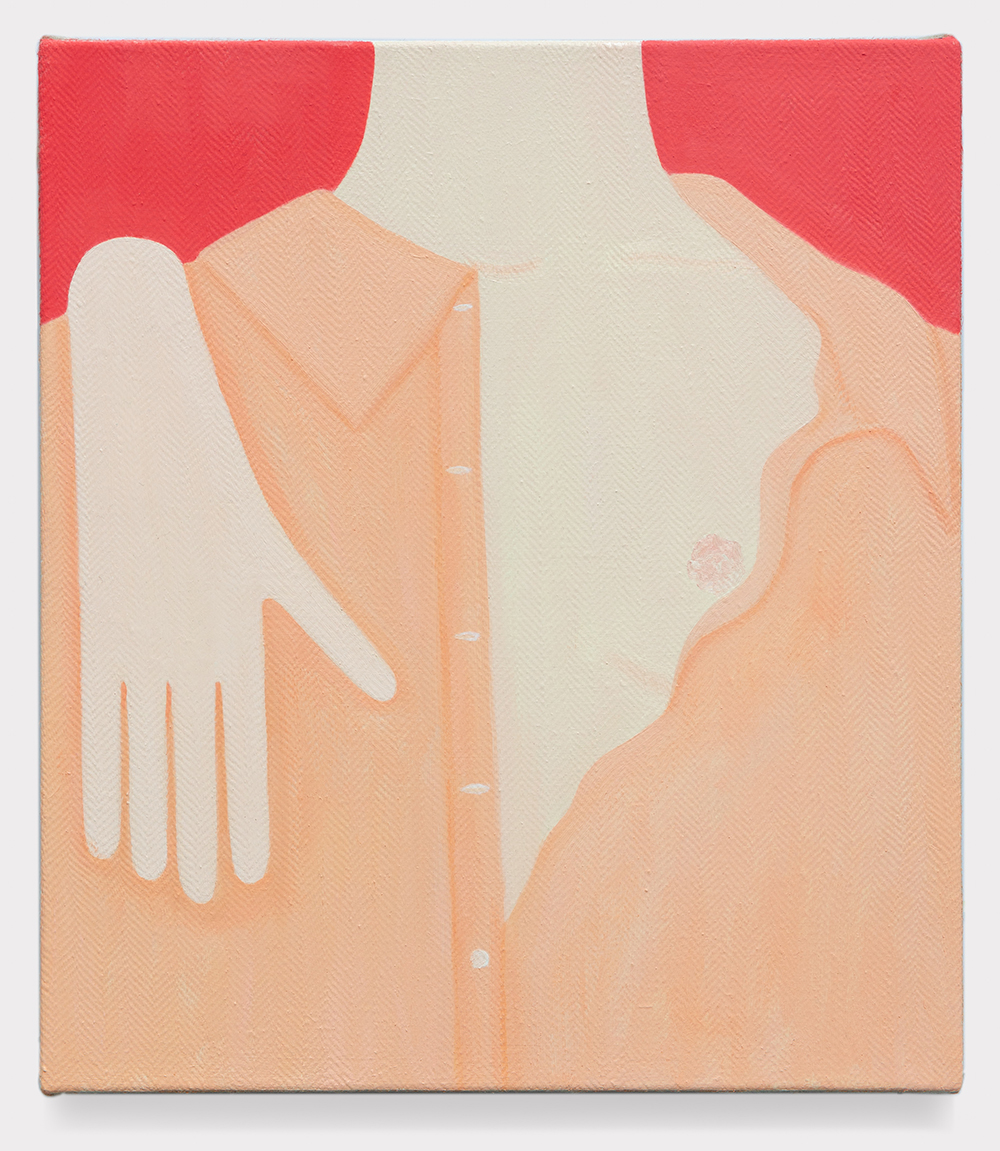

Steve Turner is pleased to present Your Hand Is A Warm Stone, a solo online exhibition by London-based Ellie MacGarry. It will consist of ten new paintings which depict cropped details of the body; garments, pockets and openings. They consider physical intimacy with one’s own body, with the hand recurring as a comforting, protective or expressive tool.

Ellie MacGarry (born 1991, Cambridge) earned an MA at the Slade School of Fine Art, London (2018) after earning a BFA at the University of Leeds (2014). She had a solo exhibition at Daniel Benjamin Gallery, London (2019) and has had works in numerous group exhibitions in Europe and the United Kingdom since 2013. Your Hand Is A Warm Stone is MacGarry’s first exhibition with Steve Turner and her first in the United States.

Ellie MacGarry in conversation with Aino Frilander

Aino Frilander:

Under the first part of the covid lockdowns, you were unable to go to your studio in London. What is it like being back? Can you describe your studio and what sort of a role it plays in your life?

Ellie MacGarry:

For the first time in my adult life I started working in my bedroom again when lockdown hit last March. It was strange because I had only very recently moved into a new studio, and one of the reasons was because it was closer to home than my previous one. I had been saying for months that I wanted the gap between my home life and my studio life to shrink, as my work comes from quite a personal place, and I was finding a kind of detachment occurring. So it was ironic that I then ended up making work in my bedroom for four months!

I found the restriction of having to work from a small desk with a limited selection of materials really challenging at first and then eventually very liberating and fruitful. The work that came out of that time has led to a lot of new work in the studio, including the work for this show at Steve Turner Gallery.

I have felt really fortunate to have my studio to escape to during the continued on and off UK lockdowns. The studio is within an artist’s co-operative called Cubitt in Islington, London. It is a special place. Lots of amazing artists have passed through there over the years and it’s unusual in that it is still run by the artists, which is empowering and helps to make it affordable. While my practice is very solitary I find it vital to be part of a larger collective energy.

AF:

I didn’t realize you’d been wanting to get closer to home! That’s funny and devastating at the same time. But to get to the work itself. Can you briefly describe your work and why you make the things that you make?

EM:

My work largely focuses on what it is to inhabit a body and the spaces that the body takes up, whether that be a shirt, a bed or a pavement.

I have an ongoing fascination with painting as a medium because of the way it can simultaneously hold so many formal and material values while also pointing to art history, narratives and feelings outside of itself as an object. The way that so much can be held in a small rectangular space and then communicated from artist to viewer still amazes me. I find art-making to be such a surprisingly effective yet open-ended language.

"My work largely focuses on what it is to inhabit a body and the spaces that the body takes up, whether that be a shirt, a bed or a pavement."

AF:

And how do you work? What is your process?

EM:

I usually have a loose plan for my paintings, either in my head, noted down in word form or as a very basic line drawing. Once I actually begin the painting the decisions are then mainly colour focused, or changes are made if something doesn’t feel right. I mostly get ideas from my everyday experiences, other artworks, books, fashion, music and film. Recently I’ve enjoyed films by Céline Sciamma and Pedro Almodóvar. In terms of fashion, there was a particular Comme des Garçons collection in 2007 which had hands stitched onto some of the designs which I’ve been looking at lately, as well as Cecilie Bahnsen and Molly Goddard.

I find my work to be very sequential, with one work leading to the next. I am increasingly comfortable with the idea of working in series. The difference between a shirt with buttons or a shirt without buttons, a deep blue or a light blue is significant enough to make a new painting.

I am interested in the banal repetitions within our daily lives – the dressing and undressing, sleeping and waking – so a somewhat repetitive practice feels right to me. I read Portraits and Repetition by Gertrude Stein recently where she writes that anything that is worth doing is worth doing again and again. Even if you set out to repeat yourself, it never will be the same the next time around.

AF:

Yes! I think we briefly talked earlier about how these covid times are so intensely repetitive. Is that so for you? For me it feels like it’s always morning or night and I have to brush my teeth.

EM:

Ha yes, I definitely felt like that in the first lockdown, but now things are much more varied as I go to my studio and the studio of another artist for whom I work. But it’s still just a relentless routine of cycling from home to work and back again.

AF:

To change gears a little, you grew up with architect parents near Cambridge. What was that like?

EM:

Yes, both my parents are architects, although my mum worked as a school teacher while I was growing up, teaching design and technology. So I think conversations about making things, and about materials, structures and spaces were always going on in the background.

My dad is an amazing draughtsman. In addition to his architectural drawings, he makes these really wonderful gouache paintings with an incredible attention to detail and a lot of humour.

My dad has also worked from home ever since I was born, so I was aware of this lifestyle of spending the whole working day by yourself at a drawing board with some music on. While this seemed like it could be a bit lonely there was also an appeal. Music was definitely important growing up. We always had so many different kinds of music on, from Eurythmics and Ali Farka Touré to Neil Young.

From quite a young age I remember fantasizing about living in a big city. My cousin opened her own gallery in London when I was a teenager so I would sometimes go with my family to exhibitions or openings there. That gave me a little insight into some contemporary artists that I probably wouldn’t have been exposed to otherwise.

AF:

Can you remember any art experiences that were significant for you at that time?

EM:

I always really liked drawing and making things, but I wasn’t someone who was set on being an artist from a young age. Even at my interview for art school I said I didn’t want to be an artist because it would be too lonely. Now being in the studio by myself is an ideal day!

AF:

Hahah! It happens!

EM:

When I was younger I thought I would like to work in fashion, so it’s funny, or perhaps not that surprising, that the body and garments have become quite central to my work now. It was only during my art foundation course that I was more drawn to image-making. I ended up specializing in printmaking and I can still see the impact of this in my work, particularly the screen-printing process of working in layers with colours drying in between, and the graphic sensibility with crisp edges.

I remember loving the series of Jim Dine robe prints at that time, and also the collection of bed-dresses by Viktor & Rolf, so it seems some influences really do stick around! In terms of exhibitions, I remember a Bridget Riley show and a Cindy Sherman show making a big impression. And I went through a period of being into drawing the armour at my local museum, The Fitzwilliam in Cambridge, which somehow makes a bit more sense to me now.

AF:

What intrigued you about the armor? There’s no explicit armour in the new show, but I suppose all clothing choices are always some sort of an armor, no?

EM:

Yes exactly. The way we cover our bodies always has some form of protective function. I find clothing can function as an emotional armour. The right clothes can make me feel strong.

AF:

You mentioned earlier that you’ve been using a Piero della Francesca book as a sort of a workbook for a while now. Can you talk more about that?

EM:

I have found Piero to be really influential ever since I first saw his paintings at the National Gallery a few years ago. But as museums and galleries have been shut, it has been a challenge not seeing work by other artists in real life.

I have this paperback Piero book which I have been referring to quite directly as a source for some of these latest paintings. Making Space is informed by Polyptych of the Misericordia — Madonna of Mercy in which Madonna raises her arms so her cloak becomes almost like a tent or shelter for the figures below her. I love the scale of it – she towers over them and both her size and this posture seem to emanate both strength and protectiveness.

I can’t get enough of Piero’s use of colour. I love the way he used capes and garments as a way to reveal a colour underneath another colour. In this case her dress acts like a solid pink column, a necessary structure for all of this cloth that shrouds her and the figures below, with little glimpses of the pink sleeves peeking through too.

Something that has struck me more recently about Piero’s work is how sometimes the skin of the figures looks like it is made of stone or bone, it is so smooth and pale. I like thinking about this perception of material play or conversion, from flesh to flat paint to stone.

AF:

Which other artists have influenced your practice? Your tightly cropped compositions of clothing and hair make me think of the Italian artist Domenico Gnoli, for one.

EM:

Gnoli is definitely an influence, although I still haven’t seen any of his work in real life. One of my aims last year was to go to Italy and see some of his paintings, but sadly that ambition has been quashed for now.

Work like his gave me the confidence to make paintings in which there wasn’t necessarily much narrative or action, just a quiet observation. I came to his work at a time when I was making a transition from very busy, patterned, more abstract paintings to much more pared back figurative ones. The space he gives to such small details was what I needed to see then.

I also love the photographer Claude Cahun who used her body as a tool to explore the performativity of gender and identity. One of the exhibitions I was able to see in the last year was a big Artemisia Gentileschi show which was mind-blowingly good – the hair and the hands and the blood! I still haven’t got over how incredible her paintings are.

Someone else I have looked to a lot lately is Luchita Hurtado. Her work seems to provide a view from the inside, exploring corporeal interiority, and the connection between body, nature and space. Others are Maria Lassnig, Joanna Piotrowska, Lisa Brice, Hieronymous Bosch, Shunga, Giorgio Morandi, Katherine Bradford.

AF:

That’s a strong lineup! The new paintings you’re showing at Steve Turner feature faceless torsos with hands slipping in and out of clothing. Touch and skin-to-skin contact have become such a rare and precious commodity recently, but I think you said that there’s also an element of anxiety that makes sense to me. Can you talk about that?

EM:

Yes, so rare and precious. The hand seems to have become a marker of touch in these new works. They stem from thinking about physical intimacy with yourself taking the place of intimacy with others – placing a hand on yourself as a comforter, a kind of self-embrace.

These thoughts around the power of skin-to-skin have subsequently further developed into thinking around foreign bodies entering into your body’s sphere, like your hand touching someone else’s, or their arm around you, gestures that now feel quite significant.

Like a lot of people I have experienced heightened anxiety around the body, health and connection in the last year and this has definitely had an impact on the work I have made. I thought about how if you are nervous you might put your hands in your pockets – burying one of the most expressive body parts. I think of pockets as quite architectural somehow, like a balcony on a building, a little extension and a place to store things. And the finger probing through a hole in the cloth represents a kind of niggling feeling. I also like the association this has with weaving – slipping in and out, under and over.

"The hand seems to have become a marker of touch in these new works. They stem from thinking about physical intimacy with yourself taking the place of intimacy with others – placing a hand on yourself as a comforter, a kind of self-embrace."

AF:

You’ve said you’re interested in how clothing can reveal the body, and you can find quite a few benign wardrobe malfunctions in your paintings. I’m just going to be weird and ask this: Do you think that the Brits have an especially awkward relationship with nudity or is that just a cliché?

EM:

You might be right! I don’t think we are generally a nation at ease with nudity, and unfortunately I think people hold a lot of shame about their bodies or exposing them. I like homing in on this though. I think awkwardness and embarrassment are ripe subjects for making art.

There is something so inherently exposing about making something and showing it to the world so I like the dual exposure in my work; that every time a work is revealed, so is the body. Each time I paint a garment on a body I see it a bit like a pair of curtains, at varying states of open or closed, revealing a glimpse of something behind. I feel like the relationship an artist has with their work is a bit like the one they might have with their body. It is ever-changing, fascinating one minute and repulsive the next.

AF:

I also love your paintings featuring hair – hair on heads, hair on bodies, and sometimes very very lush pubic hair. Can you talk about the fascination we have for hair? Is it a challenge to depict it?

For me it’s probably more challenging to talk about it than to depict it! Hair is interesting to me because it plays a role in both covering and protecting skin and also holding or displaying identity, just like clothes do, but it is literally rooted to us.

I am interested in how it remains the sole method of protection for most mammals but for us its density and function varies across our bodies. I am kind of envious of animals who are covered in thick, soft patterned fur and pubic hair is about as close as we get to that.

Hair growth can also function as a marker of time. I have an enduring fascination with haircuts because of the potential for transformation that they hold, as well as their ability to reflect changing fashions and histories.

AF:

Do you yourself have a history with bad/interesting/transformative haircuts? I cut my bangs on my own once and never did it again. I’m interested in how some people can be so free and easy about those transformations.

EM:

I have never had any disastrous ones (my friends might disagree), but I have tried a lot of different styles, from extremely short to pretty long with a little mullet along the way. I am definitely not someone who just goes and gets the same reliable haircut each time. I kind of wish I was – that must be a nice peaceful thing to do. I think I am too addicted to the thrill of taking a risk.