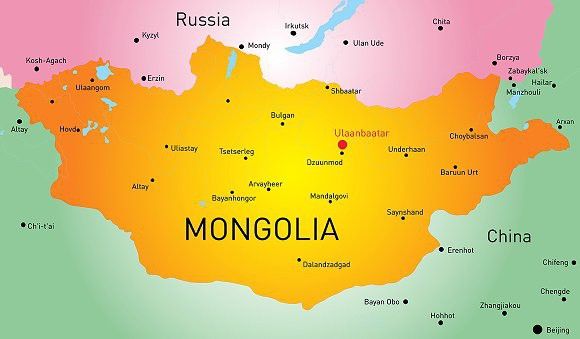

Steve Turner is pleased to present I Am Angry, a solo exhibition by Yuma Radne, an artist of Buryat heritage, born and raised in Ulaan Ude, a city in Siberian Russia just north of Mongolia. The exhibition features paintings that are inspired by life in her homeland, a place of complicated identity, a hub on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, in between Russia and China. Five of her paintings depict scowling faces whose expressions represent the anger that ethnic minorities in Russia commonly feel while Meditating, Conference and Redemption convey possible alternatives to perpetual anger.

Yuma Radne (born 2001 Ulaan Ude, Buryatia, Russia) has been creating art since she was five years old. After gaining notoriety in Ulaan Ude, she was honored with a solo exhibition at the National Museum of the Republic of Buryatia when she was only seventeen years old. Soon after, she convinced her parents to allow her to move to St. Petersburg where she studied at the Shtiglitz Academy of Fine Arts. After one year, Radne began studying in Linz, Austria and one year later she enrolled at the Art Academy, Vienna where she is still enrolled. I Am Angry is Radne’s debut solo exhibition in the United States.

Yuma Radne in conversation with Steve Turner

Steve Turner:

Interesting artists often have interesting biographies. You are no exception. Can you describe your background up until the time you left your family home?

Yuma Radne:

I was born in Ulaan Ude, the capital city of the Buryatia Republic, which now belongs to Russia, and which is just north of present-day Mongolia. I have a big family. I am the second of three children. I don't remember my first conscious painting, but somehow I always knew that I would become a painter.

ST:

Do you recall any early art experiences?

YR:

My parents later told me I painted on the wallpaper when I was two years old, behind the sofa or on the furniture. At age five, they sent me to an art school which had classes after my regular school. I went there until I was fifteen. During my teenage years I read a lot of books including titles by Hemingway, Salinger and Fitzgerald. This made me question school and I became a little rebellious. I used to skip classes and just walk around the city, making sketches of homeless people that had nothing to do except wander around, just like I did. I argued with my teachers and drew or read during class. My parents bought me an easel for my birthday. I turned my room into a studio. I put something on the walls to protect them, a layer of linoleum on the floor, and I moved the furniture to the side. In this way I had a studio that was around two by two meters.

ST:

Were your parents supportive of your desire to become a painter

YR:

Absolutely! They bought all of my materials. I am so grateful and lucky for this. More importantly, they helped and supported me to move out and study abroad.

ST:

What were you painting in those early years?

YR:

I started thinking about my identity, being Mongolian in a Russian-speaking world, where we are not represented, and even worse, we were oppressed. When I was fifteen I started a big series of paintings which depicted Mongolian women. I was active on Instagram and soon gained some kind of popularity in my hometown. Newspapers started to write about me. Then I was featured on television shows and on YouTube and on blogs. Then I was invited to show my paintings at the National Museum of the Republic of Buryatia. It was my first solo show. I was seventeen and I soon stopped going to school as I was painting full time. I had a plan to go to Europe.

ST:

Can you describe Ulaan Ude?

YM:

It has around 400,000 people and is one of the oldest cities in Siberia. It is a very special city with lots of monuments and history. It is often described as the junction of east and west and is on the line of the Trans Siberian Railroad which connects Moscow to Vladivostok.

ST:

What do most people do to earn a living? What does your family do?

YR:

There is manufacturing connected to the railroad and to Russian defense. There also is a glass industry, and outside of the city center there is agriculture. Unfortunately, there also is a lot of poverty. My parents own a tech business.

ST:

Since your work incorporates so much imagery from Mongolia, please describe the scenes that you encountered in daily life which now inspire you so much.

YR:

From my childhood I think of buddhist temples, green tea, lots of animals (sheep, cows and horses), building a yurt on a hot summer day, celebrating Surkharbaan (a Buryat sports festival) and Tsagaan Sar (lunar new year). Otherwise, I think it provides a pretty normal life, just like most other places.

ST:

Did you decide early on that you would need to leave Ulaan Ude to become an artist? What were some cities in which you dreamed of living? How did you learn about the rest of the world, and about the art that was made elsewhere?

YM:

I started to learn about art history and other general knowledge on youtube when I was fourteen. I watched documentaries about Picasso, Matisse, Cezanne as well as many nerdy videos where two people would discuss one subject or another. I learned so much, but it was mostly about the period between old master painting and modern art, but not so much about contemporary art. Not surprisingly, it was a very western view of art history, which I think explains why I was so determined to go to the west. I knew that so much happened in New York, Paris and London. I also really liked Klimt and Schiele, somewhat of a cliché I know, but I was mesmerized by Vienna and decided that I would end up there.

ST:

How old were you when you left Ulaan Ude to pursue your art studies? Can you describe the circumstances that led to this big move? Where did you go?

YR:

I was seventeen when I left home to go to Saint Petersburg to study painting at the Shtiglitz Academy of Fine Arts. I wanted to move far away from home to begin living an adult life, one which would enable me to pursue my artistic dreams. This did not come easily as I had to get the blessing of my parents, something I only got after my solo exhibition in Ulaan Ude. My parents didn't really take my dream seriously until then. They thought I would become a designer or an architect until some older painters from the region of Buryatia – Balzhinima Dorzhiev, Zorikto Dorzhiev and Zandan Dugarov – attended my opening in 2018. My parents asked them if they considered my paintings to be any good and whether I had talent. The painters spoke well of me and this made a big difference. My parents had confirmation from respected painters. “Your daughter is an artist!”

ST:

Did you enjoy living in Saint Petersburg? Can you describe your experience at the Shtiglitz Academy of Fine Arts.

YR:

I really enjoyed the taste of adult life. I was renting a tiny flat in a hipster district, close to a theater academy. I remember seeing people dancing or singing in my backyard. My academy was nearby, housed in a huge and beautiful building. It felt so special to be there. The academy has had a lot of history, with many notable artists having studied there. I was in a very large city compared to my hometown, in the country’s cultural capital, and I was studying at one of the coolest art academies in Russia. It was an honor, but it also was a disaster.

Going in, I knew that they taught a very traditional type of art there and that art history for them stopped in 1900. Believe it or not, they considered Gauguin to be contemporary. I studied monumental painting there. It was one of the oldest departments in the academy, I chose it because it was the closest thing to easel painting. There were a few really nice artsy guys, but mostly I was surrounded by a sort of Christian Russian, in their thirties, with long beards, who never could understand anything outside of their own bubble. All they cared about was Christian art. Their biggest ambition was to be a church painter. I don't have a problem with this religion in particular, but I did not want to be surrounded by such fundamentalist and conservative views while I was so young and impressionable. I experienced a huge cultural shock there, and unfortunately, I also encountered a lot of racism. Professors and classmates would treat me and my work differently because of my race. I was not bullied, but I was treated as a second-class person. For them, White Russians come first, and Central Asian immigrants come a distant second, and Asians in general are not welcome. This is a very complicated and deep problem in Russia, one that is seldom acknowledged.

ST:

Were there other women in the academy? Were they similarly poorly treated?

YR:

Actually, there were many strong women in my class who had good technical knowledge. I wouldn't say they were poorly treated, but a couple of times I’d hear from professors something like: “Oh, these works are great, but I cannot count on you. You're a woman, you're going to get married…” Or “When we have a choice whom to accept, of course we choose a man. It's monumental painting we're talking about, it's not designed for women.” But sometimes they would also say: “Some women are so much better at painting than men.”

ST:

What were some of the positive aspects of studying there?

YR:

I learned to work hard. When I was painting at home, under my parents’ roof, I could always take a break or sleep for eleven hours. I had time. It was chill. In Saint Petersburg, I started to work more than I slept. I would wake up and paint. I would paint at all hours, and for a while, I loved it, even when I was copying a painting that I hated, drawing a skull, or learning about anatomy and the skeleton.

ST:

What was it like to have a museum like the Hermitage in the city where you lived? Did you visit often? Which works were especially meaningful to you?

YR:

I had art history courses in Hermitage almost every week, and as a Shtiglitz student, I could enter the museum for a reduced price, so I went there very often. My most vivid memory is of Matisse’s Dance, but I also enjoyed seeing works by Titian, Rembrandt and Velázquez. The museum is so huge that it is said that one can only see everything if you spend eleven years there.

ST:

What made you want to leave Saint Petersburg?

YR:

I was painting so much that my hands started to hurt. Sometimes I would forget to eat, and then I would come home to work on paintings that really meant something to me. That excited me and it made me long for a more inspiring situation. Because I was painting late into the night in my flat, I was often extremely tired, and at some point I started to hate the city and the academy with its strict rules. I ultimately stopped doing anything. I fell ill and didn't go anywhere for a month or two. I desperately wanted to move abroad, I felt a bit defeated, so I took my things from the academy and never returned. I sent my portfolio to the Art Academy in Vienna but I missed the deadline. I then learned of another academy in Linz, flew there in the summer, took the entrance exam and was admitted.

ST:

Did you speak German already? How was the transition to living outside Russia?YR

I understood a little German, not enough to speak about my art, but enough to feel comfortable. I was nearly fluent in English, and that was useful. Studying in Linz was much more relaxed. I had a nice studio in the city center and I attended classes. I used this year to socialize more, to meet new people, to experience Austria, and to develop more balance in my life. I was still the last artist in the studios at night but I was less hardcore. The crazy competitiveness of Saint Petersburg was gone and I found the people to be much more open-minded and friendly. I made friends easily and I really enjoyed my time there.

ST:

Did you then transfer to the Academy in Vienna?

YR:

When the academic year ended in Linz, I moved to Vienna. I applied to the academy again, and this time my application was on time and I was accepted. I have been living in Vienna since 2020 and I very much enjoy the academy and my classes. It is exactly what I was looking for. I am surrounded by motivated people, artists who are very cool and who have strong ambition. We are all together in the studio 24/7, in the center of Vienna, seeing each other from morning to night, sharing lunches and secrets. I feel like we are one big crazy family. In the academy we have this museum with Bosch’s paintings, where we have free access. It is just two floors away from our studios. We have a cafeteria, where we sit and gossip all the time. We have a park in front of the academy, where we drink coffee on sunny days. And of course, we have a backyard, where we have parties. I'm not exaggerating at all when I describe my life in the academy. It's really like this – super fun and amazing – with a pinch of drama as well.

ST:

After the darkness of Saint Petersburg, you must be in heaven. How has this encouraging environment affected your own work? Have certain professors been especially helpful?

YR:

There were so many professors in Saint Petersburg, who have helped me a lot, who pushed me hard and understood me. What I really liked about Russian professors is that they are not afraid to tell you directly, “This painting is shit. Keep trying.” This approach is not as common in Western Europe where people are more sensitive to harsh criticism and professors don't usually make such strong statements about their students’ work. It is a completely different approach. I suppose this is because art students in the west are more developed than those in Russia so professors speak to students as artist to artist rather than teacher to student.

When I reflect back, I have been lucky to have had good teachers everywhere. While growing up in Ulaan Ude, I met many talented older people who influenced me, both in my art school and outside. There were painters, sculptors and a couple of movie directors. Then I had the hardcore teachers in Saint Petersburg, who were a bit old school, but in retrospect, I greatly value that experience. In Linz, I had good professors too. They encouraged me to experiment more with my ideas than with my techniques. In Vienna, oh my God, there are so many great professors and different kinds of artists who have taught me so much. I am so very happy that I chose to study in Vienna.

ST:

Let’s talk about your recent works. As I look at the work of the last couple of years, it seems that you really found a way to express yourself with color. Can you describe your evolution in this respect?

YR:

In Saint Petersburg, one of the professors in the monumental painting department told me that I was not a painter, that I had a graphic approach. I completely disagreed and I was so irritated by his characterization. Did he just call me a graphic painter? Looking back at my works from 2018, I see that I was using black for shadows and white for light. I find that pretty boring now, but I continued studying color theory in Saint Petersburg and in Linz, and tried many different things in each city. Then in Vienna, I dove deeper into my study of color theory and also experimented with different materials. For a short period, I abandoned color, using only umber, ochre, white and black. I thought that by isolating myself from color I would better understand it. Then when I started using color again, my paintings got a lot more colorful and in a more purposeful way. I began to use complementary colors. For example, I would juxtapose a yellow light with a purple shadow and I used five or six layers of different colors to create rich, deep contrasts. It was a lot of fun. For me, color is very often more important than the object that I am depicting. For example, I painted a red mushroom in the bottom right corner of a painting, not because it had to exist in that painting but because I needed a red dot there.

ST:

I also see a lot more imagination and inventiveness in your most recent works. You depict groups of characters that are fanciful and colorful. Some appear to have clothing that might be from Buryatia. Others are naked. Who are these figures and what do they represent to you?

YR:

Thank you! Well, I heard a quote that a painting is a living organism, and that a painter is someone who can hear what it tells him to do. In some way, these characters just came to me, I didn't decide to start painting yellow aliens, redheads or angry people. They just somehow appeared. I think I need more time to know who they are and what they represent. I am still processing it and I need to make more paintings before I will know.

ST:

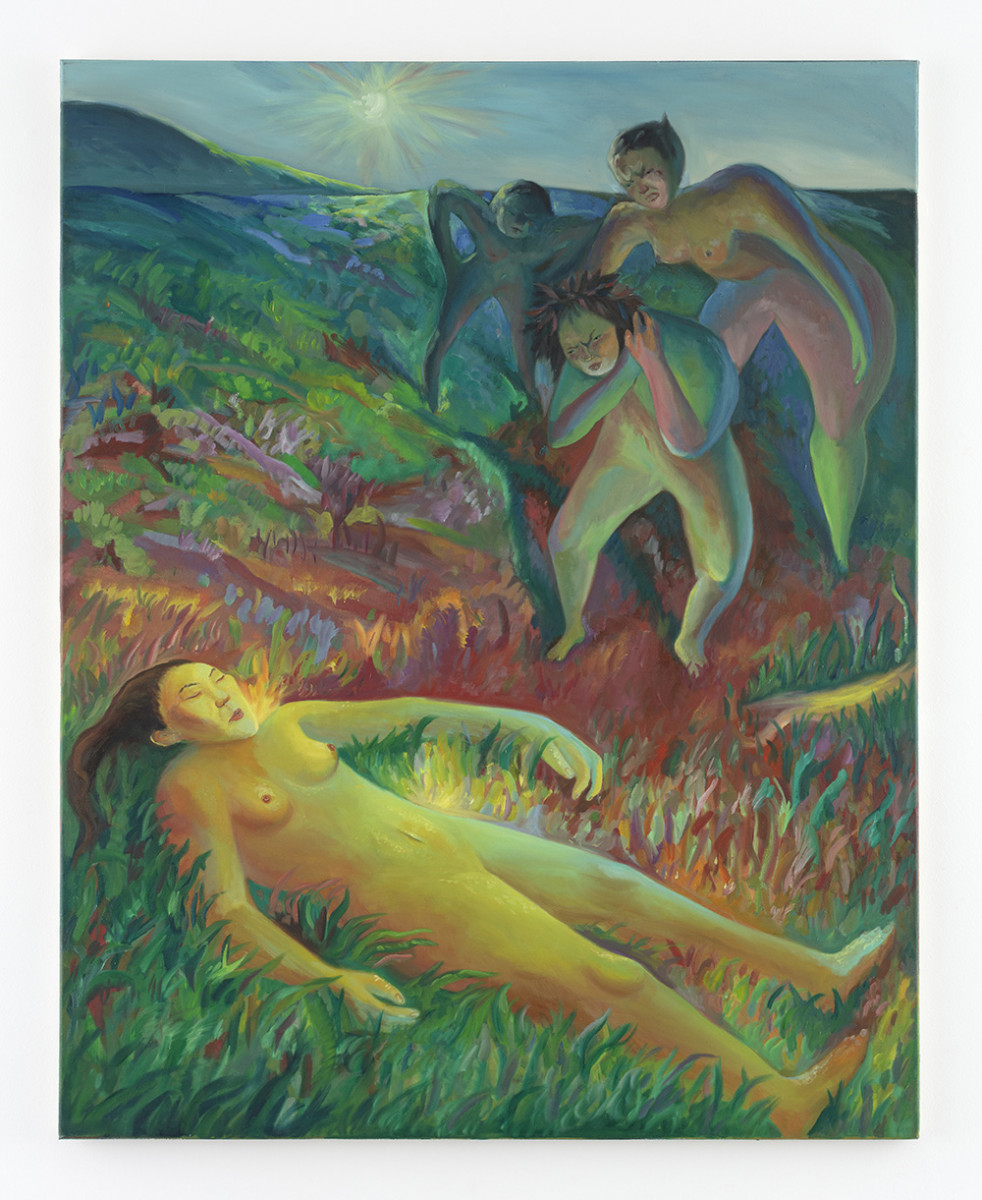

I am specifically referring to three paintings, Conference, Meditating and Redemption, which will be part of your May 2023 exhibition in Los Angeles. Would you describe the inspiration for each of these three works?

YR:

Sure! For Conference I wanted to create a magical scene of a round table with people eating all around it. Sometimes a title precedes the actual painting. This happened with Conference where the creatures are not friends but are there to discuss a problem.

Meditating is a very abstract painting to me, I just wanted to paint a vertical work where the cold blue is changing to warm reds and yellows. All the rest, the characters and the narrative is secondary to me.

Redemption was painted in April 2022 during the early days of the war in Ukraine, when some people in Buryatia were speaking out against the war, going to prison for it or were leaving home forever. The yellow bird character was my main character at that time and she represents freedom.

ST:

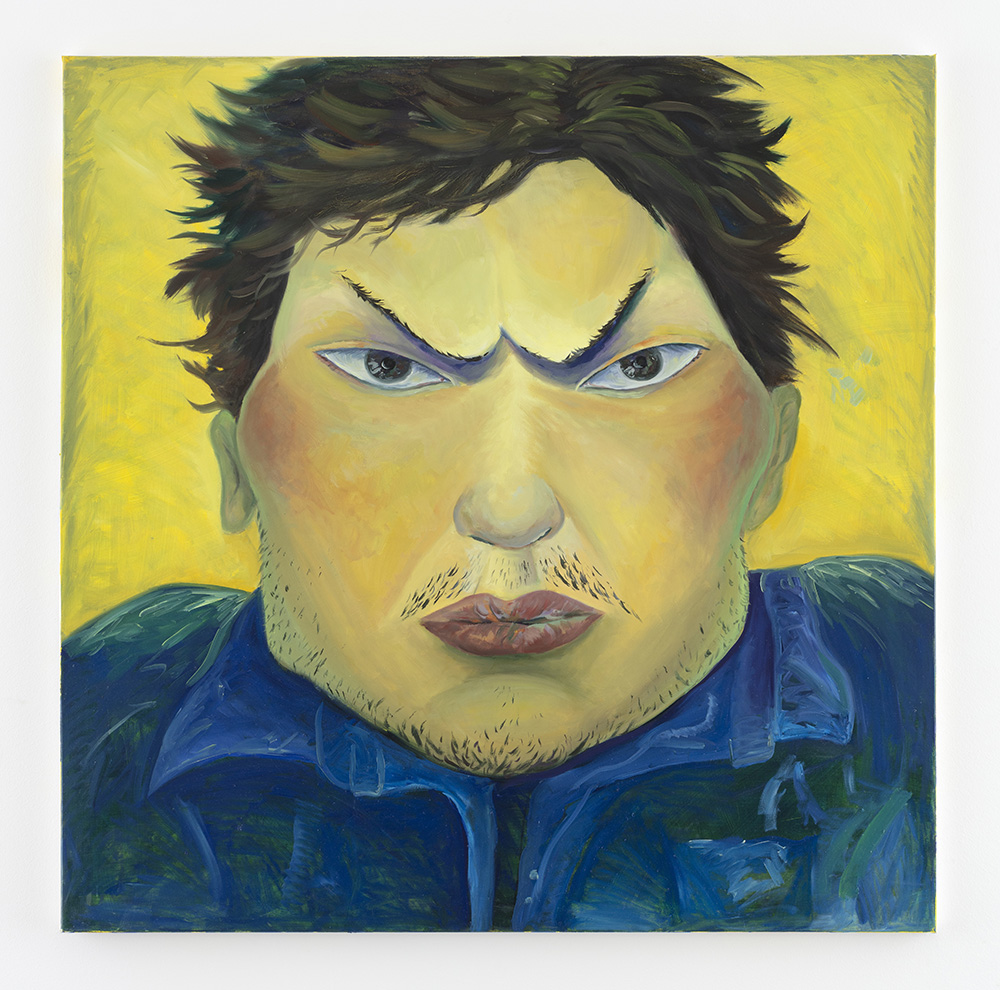

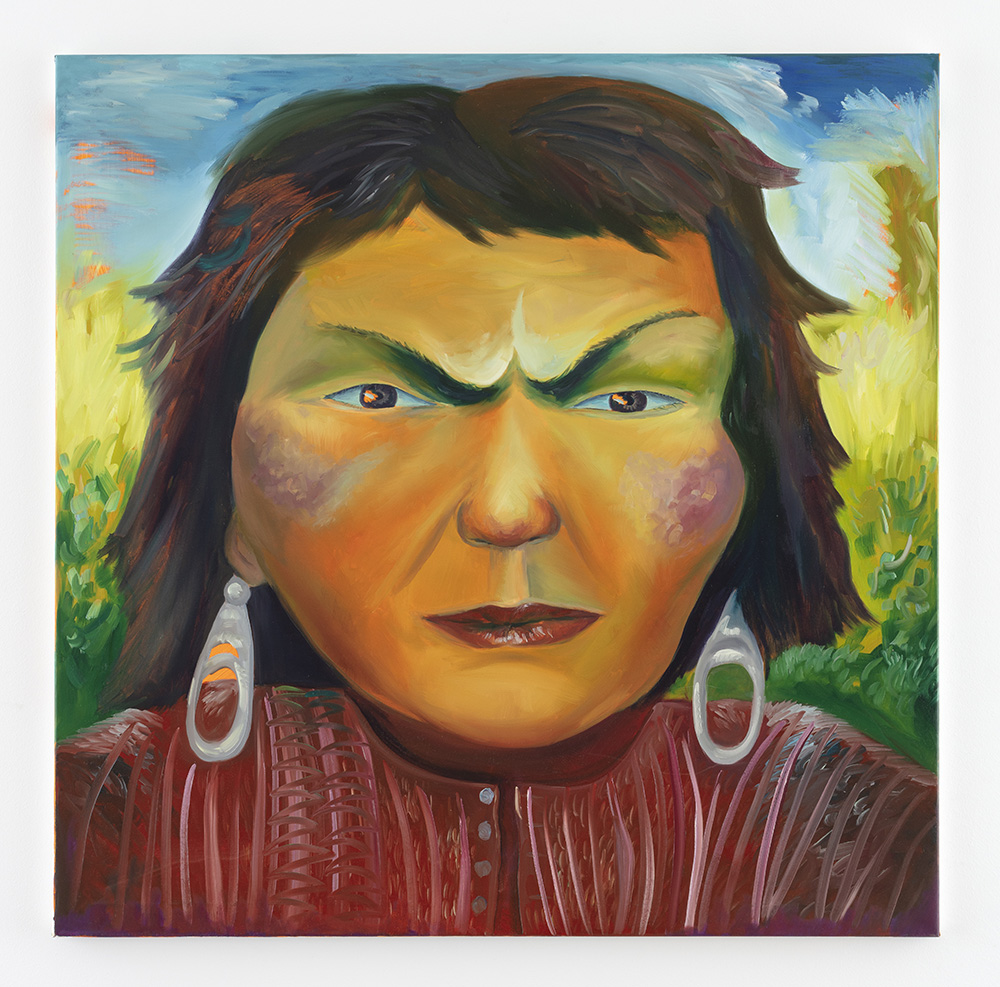

Your exhibition is titled I Am Angry, and it includes a group of portraits entitled Angry Girl, Angry Boy, Angry Mother and Angry Grandma. Is this you and your family? Why is everyone angry?

YR:

No, these portraits are imaginary angry people who have their reasons to be angry. It started with an angry girl which I thought of as a self-portrait. But then I wanted to expand to multiple generations of women, so that's how Angry Mother and Angry Grandma came about. I felt that something was missing so added an angry boy. They represent the minorities who live in Russia.

ST:

The juxtaposition of the Angry portraits and Conference, Meditating and Redemption is noteworthy to me. I interpret the latter three paintings as possible ways of managing anger. One might discuss or meditate to cope with anger and redemption could follow. Does this interpretation resonate with you?

YR:

It's such an interesting interpretation! It really does make sense as I painted all but Meditating at the same time, and it followed only a year later. When I created them, in March 2022, I was very angry. I am generally a very calm person, someone who is rather slow to become angry. For a long time, I thought that anger was a very unwise emotion and I avoided it. Whenever something came up that should have elicited anger, I instead felt sad. At some point, I started to reflect on it and tantric buddhism where one can transform anger into enlightenment in various ways including meditation. I have since accepted that anger is a powerful emotion and that it also encompasses a kind of beauty.