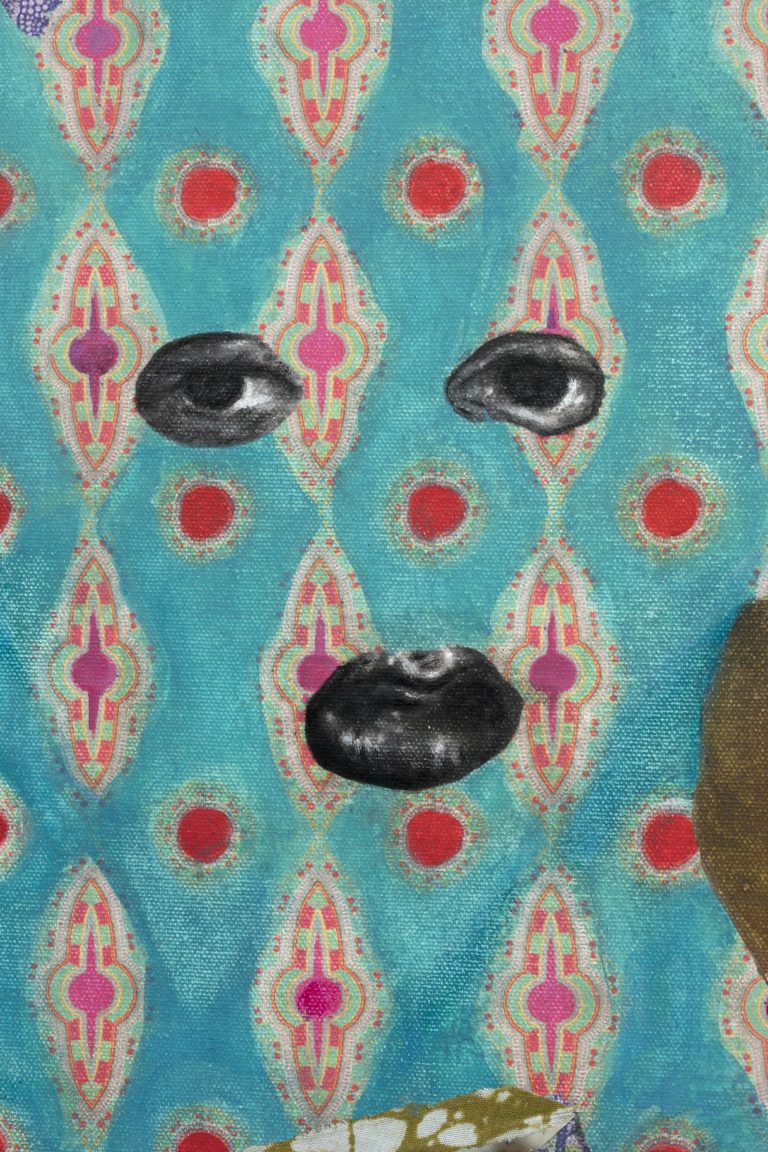

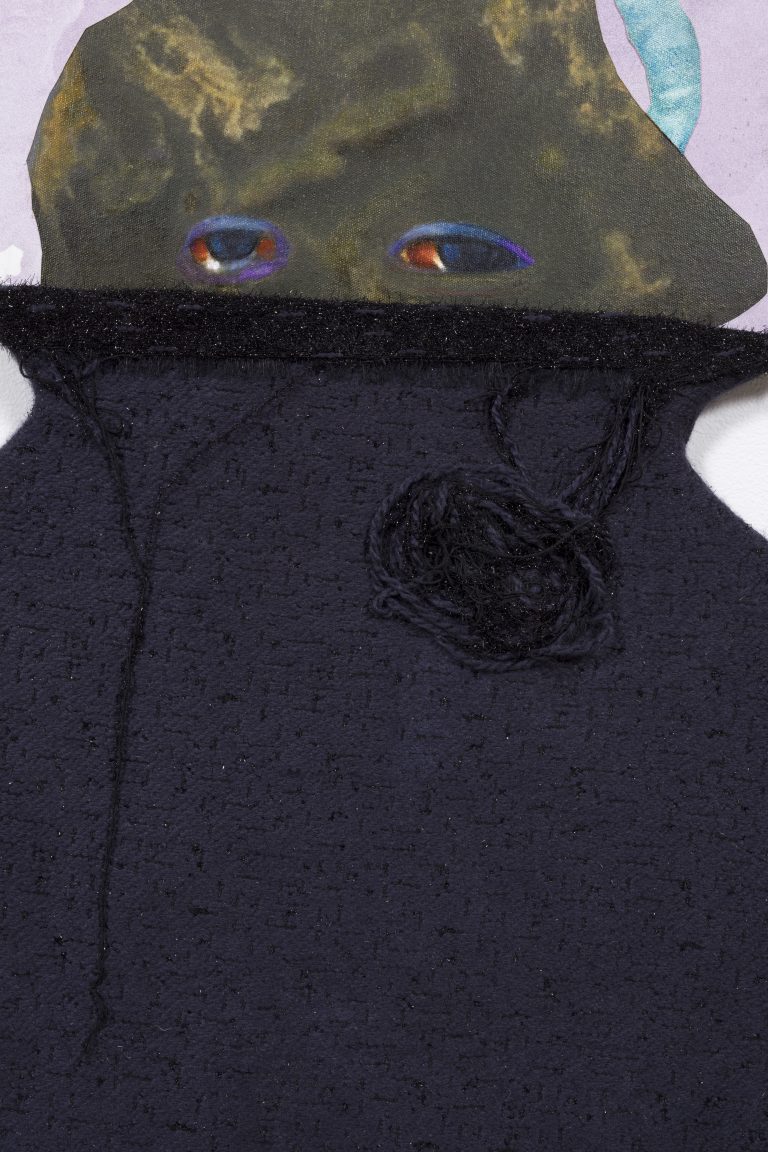

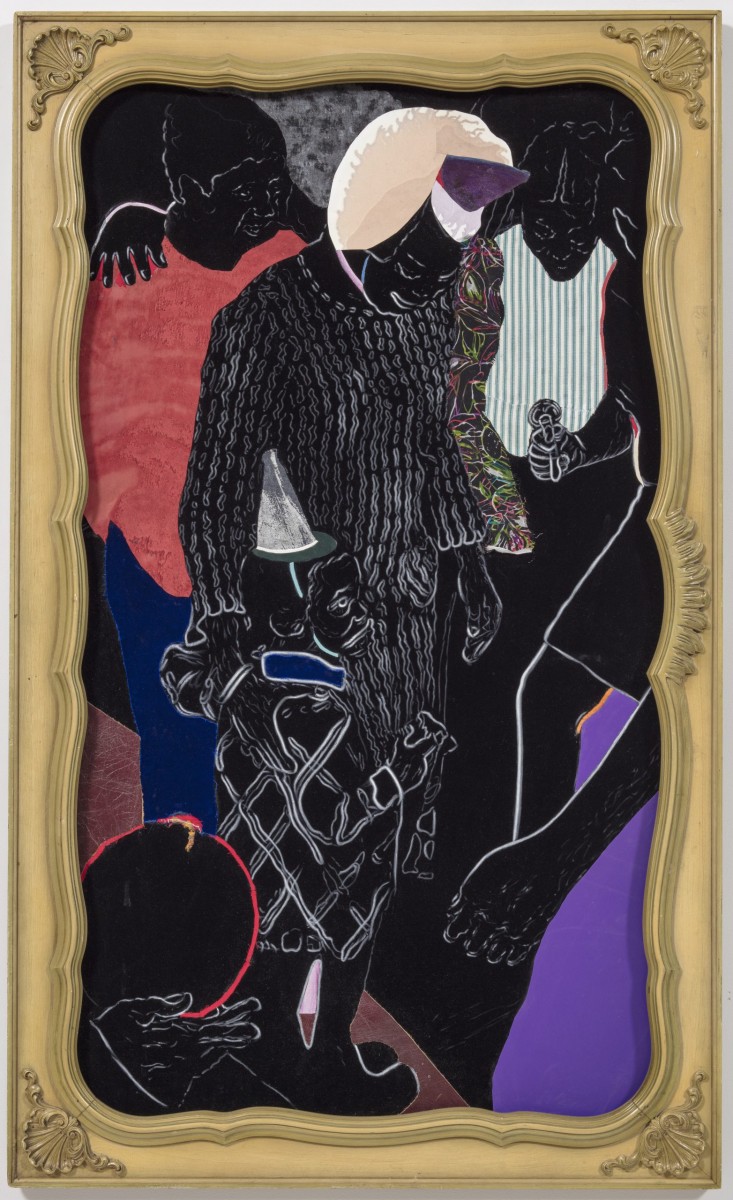

David Shrobe (born 1974, New York) creates multi-layered portraits by repurposing everyday materials that he finds in his Harlem neighborhood. He disassembles furniture, separating wood from fabric and recombines them as supports for collage, painting and drawing. In doing so, he excavates history to create fragmented portraits that relate to his family history. Many of his works are oval in shape, and with their use of fabric, they bear a faint relationship to early daguerreian portrait photography, especially the early images of Frederick Douglass. By combining the found and repurposed materials of Harlem with the photographic history of African Americans, Shrobe produces new narratives that feel intimate and personal without being anchored to a specific time or place.

The interview below from Artofchoice.co was released on the occasion of Shrobe's 2020 solo exhibition, Walk the Air, at Steve Turner.

David Shrobe repurposes detritus to reimagine history

Interview by Emma Grayson

Tell us about yourself? Where are you from and when did art first enter your life?

I was born, and grew up in New York City. The arts in one form or another have pretty much always been a part of my life, being raised in an apartment where my father, a jazz pianist, held jam sessions in our living room and my mother, who is a classically trained singer, often sang throughout our home. I kept a sketch book and loved to draw since around age 12, and was soon after thrown down, as graffiti writers would say, with my first graffiti crew where most of my friends were old school writers and club kids, which had a major influence on the art I made for many years. Painting later became my main concentration and I decided to pursue my formal training at Hunter College where I earned my BFA and MFA in Painting.

What historical movements have influenced your art the most?

Some of the historical movements that have, and continue to, inform my work are movements of resistance, rebellion, and revolution; to name a few, the Haitian Revolution, the US antislavery and civil rights movements. I’m particularly drawn to uncharted historical moments. Portraiture in classical painting, engravings and etchings especially 15th through 18th century, and early photography are also influences, such as Daguerrean portrait photography by early African American photographers, which was a movement in its own right. The current uprising for justice and equality, calling for the end of systemic racism and police brutality against black people has been extremely influential in my recent body of work currently on view.

Why is the framing of your work nearly as important as the work itself?

I think that framing, especially in the oval frames I use is a way to play with the history of portraiture and the concept of time, using them to suggest portals into imagined futures. In more recent works, the found objects become framing elements that contribute to the narrative of a work. For example, with a vintage framed mirror, I removed the glass, and used the remainder solely as a frame. What does that tell the viewer about the figure depicted within that frame? What narrative begins to emerge through the gaze of the subject or with the viewer? Is the viewer looking at a reflection of themselves as they would in a traditional mirror, or is the image reflected back completely new capturing the life of another? I’m interested in the physical space the work occupies. The work bleeds out past the canvas or wood and into the frame and beyond where the narrative continues.

Where do you source your materials?

My studio is currently housed in an apartment that has been in my family for nearly a century in central Harlem. Some of the materials are family heirlooms that have been handed down generations, such as pieces of quilts and fabric, while others come directly from architectural elements from the home such as doorknobs, window molding or damaged fixtures and such. But I seem to find the most interesting objects from the surrounding neighborhood, sometimes they’re directly outside the building and I feel like they find me. Right now, being in the midst of a pandemic, I’ve been using more of the found materials I’ve collected over the years. There’s so much beauty and power inherent in them, and they have many of their own stories to tell; they just need a little care and minor tweaking, but not too much that they lose their sense of soul or character.

Has your work always taken on the style it currently embodies?

Not at all, the work keeps changing and evolving. I think it has to for me to stay engaged and excited about making new work. My first painting was a small portrait of my two sisters but later the work became more abstract. During my MFA work, I was making these massive oil paintings on canvas and large transfers. Later they became more like painting constructions and arrangements made up of fragments to create the whole. And now I’ve found myself somewhat back where I began, working with portraits but now they’ve expanded to include more mixed media and various fabrics, metals, wood and furniture parts.

How do you start a work?

They often start with the found material that informs the direction the work takes. It’s about responding to the things I find which takes the work to unexpected places. My process is very intuitive, and I’m always looking for a kind of satisfaction or resolution. I have to surprise myself during the process of a new project or I feel as if the work isn’t doing something new enough for me. I also use my own photography as the impetus for some of the works or images sourced from an archive of imagery I’ve been building since undergrad.

What is a day in the studio like for you?

When I walk in the studio, I always make some tea, usually green. I don’t always dive right in and pick up where I left off the previous day. I like to let things happen naturally when I can. Some days, I spend the morning simply responding to emails or reading, or catching up on an unrelated task like cleaning the studio, and then I randomly glance up at what I was working on the day before, and am moved to jump right back in. My work is guided by what the painting or work calls for at any given moment, which for the most part is very intuitive. I also often arrive at the studio with a song in my head that I then need to play aloud. This song can sometimes set the mood for the day and help me find my way back into a work or even inform it. This week it was a song by Michael Kiwanuka. The connection I have to both music and painting is pretty cathartic and a palpable part of my practice. I begin many works while they are laying on the studio floor, and sort of dancing around them feeding off their energy and to the sound around me which at times can guide my next move.

Does your work aim to tell a narrative?

Yes and no; there are many layers that contribute to the narrative of my work. There is the narrative I am sometimes intending to convey and then there is the narrative the combined materials are communicating. Even the objects I reuse tell their own story, and in the process of making a work, through my manipulation and reinterpretation of the material, many connections and relationships and even histories begin to emerge in the manifestation of painting. I think the action of reinterpreting the found material itself is just as powerful as what the work may convey.

You were the first artist-in-residence at Sugar Hill Children’s Museum. Why do you think it is important to expose children to art at an early age?

This residency was a very special experience at what I would consider a very unique museum. As an act of social justice, the museum incorporated a teaching component into the residency that involved making contemporary art accessible to children. There is a preschool connected to the museum where I was able to teach art to and collaborate on projects with the young children during my residency. Most of the children were 4 or 5 years old. Children at this age are beginning to see themselves as part of the world around them, and it’s such a ripe age for discovery; they are so eager to experiment and absorb everything. Teaching children that it is ok to experiment and express themselves freely as they see fit is crucial to their identity formation. Art allows them to learn this lesson very early on without judgment. I learned a lot about myself during this residency working with the children, especially as I was about to enter fatherhood at that time. The icing on the cake was that the museum is housed in Harlem, near where I had been living for many years and in a community to which I feel a deep connection.

What do you have coming up next?

I currently have a solo show up in LA at Steve Turner Gallery Los Angeles that runs through August 29th, 2020. I’m also participating in a group show in Rome, Italy with an exciting small group of artists opening this upcoming fall at Galleria Anna Marra.

At the end of every interview, we like to ask you to give us an artist or a few artists to recommend for us to check out. Who would you suggest?

Patrick Quarm, Aaron Fowler, Sasha Gordon, and Enrico Riley.