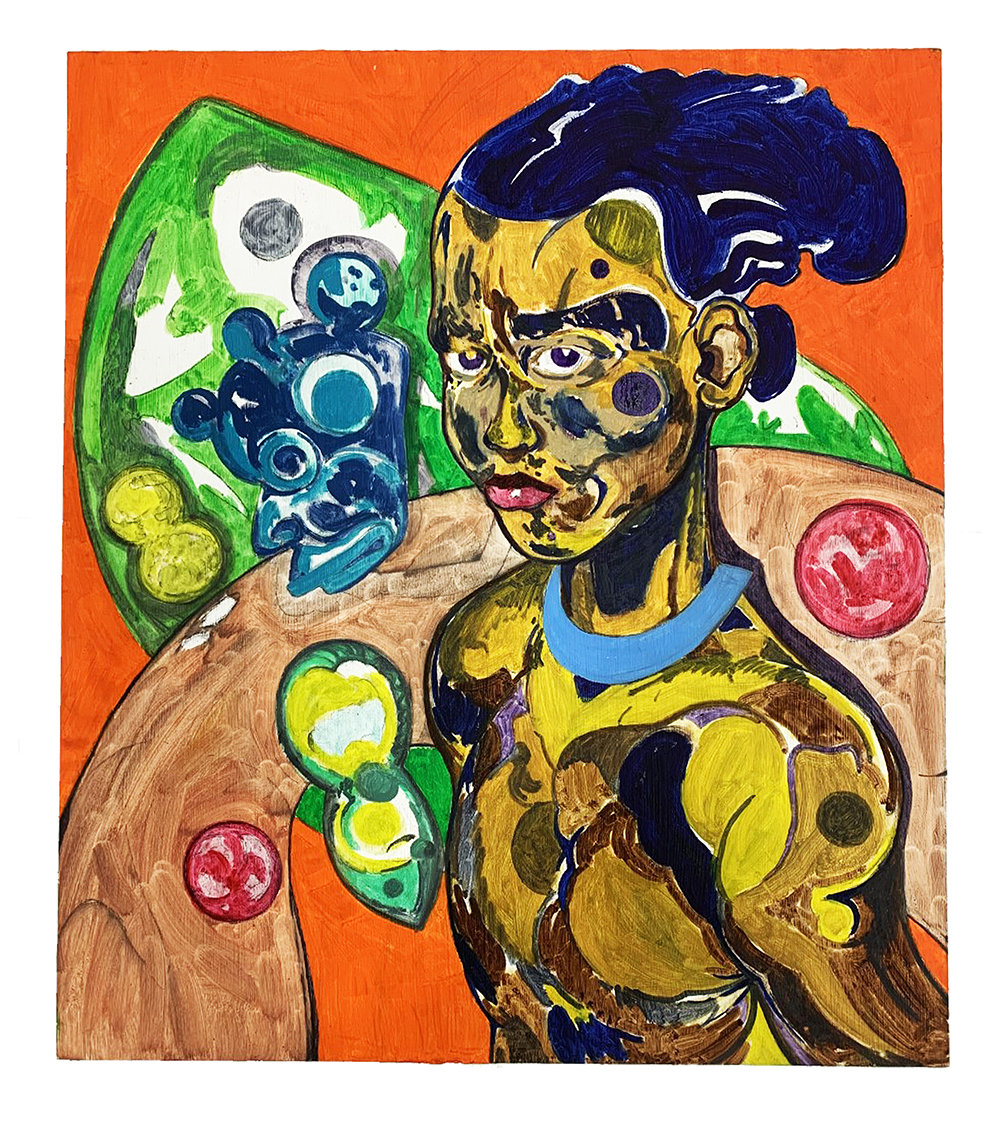

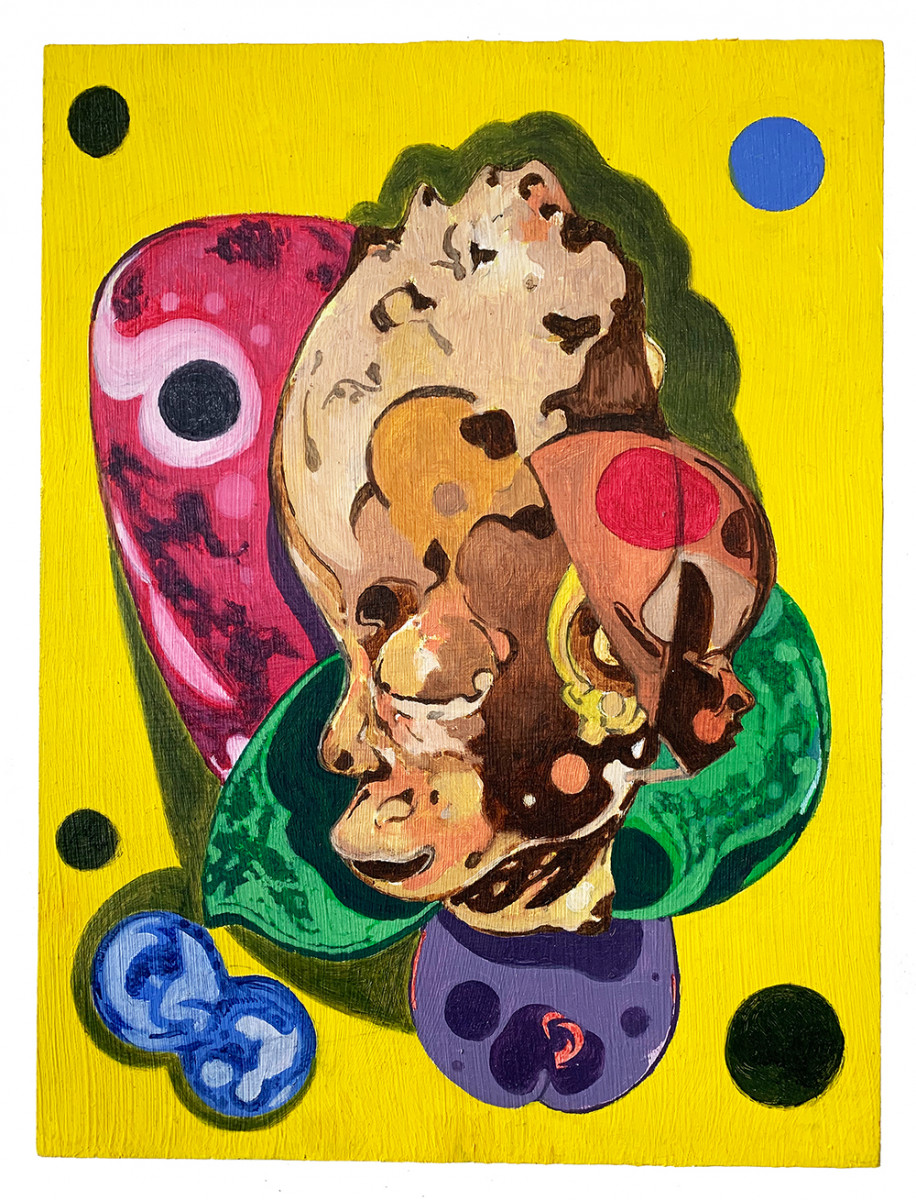

Richard Ayodeji Ikhide: Cosmic Memory

Steve Turner is pleased to present Cosmic Memory, an online solo exhibition of recent paintings by London-based Richard Ayodeji Ikhide that include images inspired by his Nigerian heritage as well as his interest in other civilizations and mythologies. The works have a figurative core, but they are completed with colorful abstract gestures and patterns. According to Ikhide, “Many cultural histories converge in my work. During the course of my life, I have absorbed a lot of information, and when I make work, I intuitively respond to it and my life experiences. In doing so, I aim to bring together past, present and future as well as multiple geographies and cultures."

Richard Ayodeji Ikhide (b. 1991, Nigeria,) earned a BA in textile design at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts, London (2014) and Postgraduate Diploma at The Royal Drawing School, London (2017). He has had solo exhibitions at the Zabludowicz Collection, London (2019) and V.O. Curations, London (2021). Cosmic Memory is his first exhibition at Steve Turner and his first in the United States.

Steve Turner:

Your works instantly resonated with me as distinct. Before we talk about them, let’s discuss your past to see how it might have influenced your evolution as an artist. Can you start with a description of your family and your years in Nigeria?

Richard Ayodeji Ikhide:

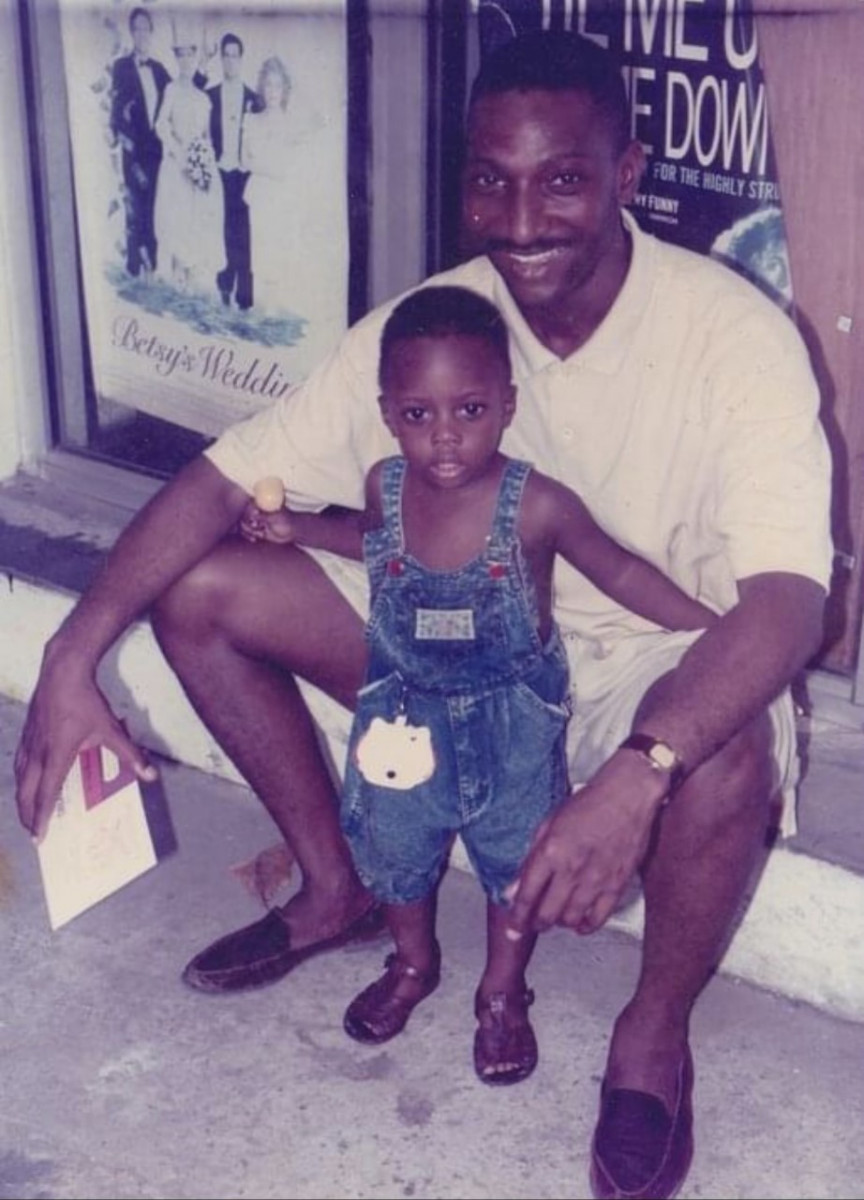

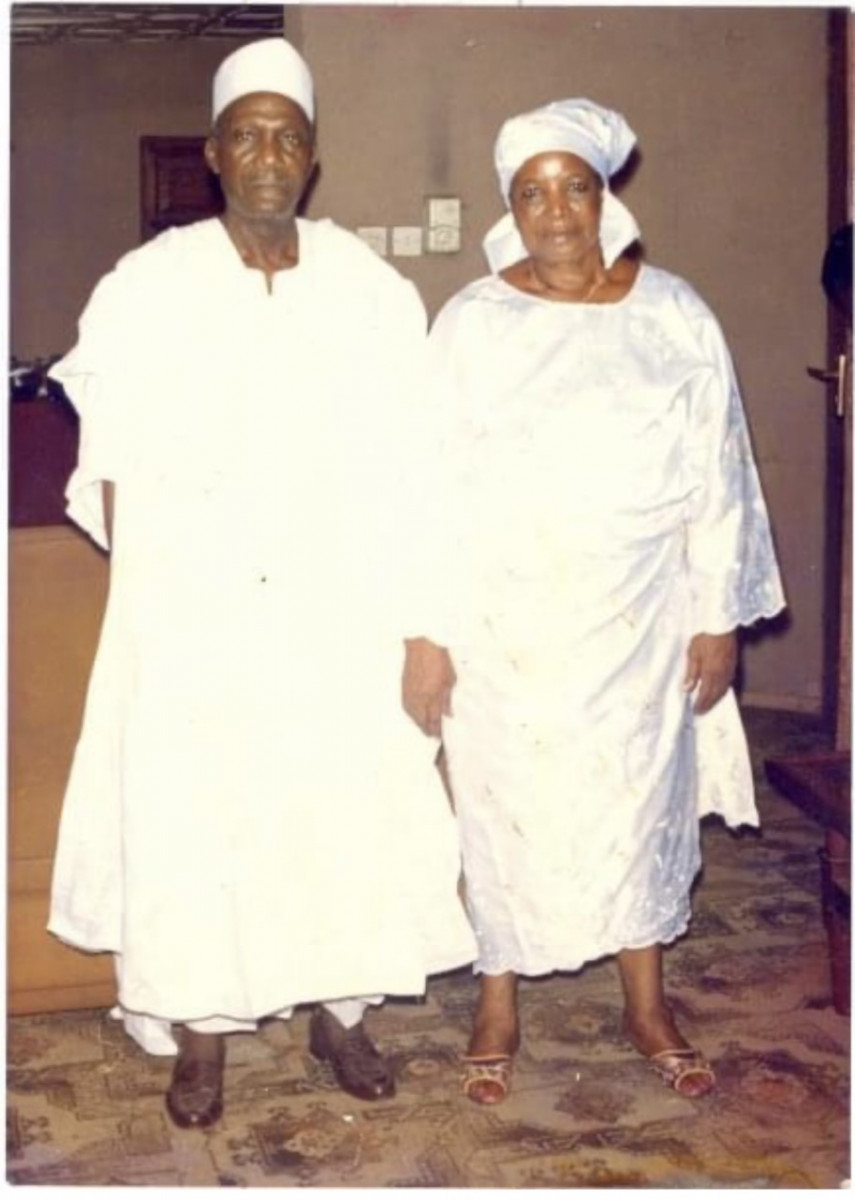

I come from a large family as my grandfather had two wives and twelve children. My father was his first son and I am my father’s first son. My family is from Sabongida Ora, a town located in the state of Edo which was originally part of the Benin Empire. My grandfather would often tell me stories about Benin and the different traditions and customs within our culture. He was a chief and so was his father before him. My grandfather instilled in me a strong sense of self and a pride for our heritage. He would say: “You must always remember that you are a proud Edo man.”

I spent most of my formative years living at my grandparents’ home in Lagos alongside numerous cousins and other family friends. It was chaotic at times, but I treasure the many memories of that busy household.

Growing up in Nigeria has certainly influenced my work. That is my heritage. Though I have lived in England for more than eleven years, I still consider myself a Nigerian and nothing can change that. Wherever I might live, Nigeria will always be my real home and that is where most of my family still resides. When I moved to England, I was already fourteen years old and deeply conscious of my Nigerian identity.

When I was young I wanted to be an archeologist. My father made my brother and me watch documentaries on the Discovery Channel every Sunday and this sparked my interest in the ancient world. He also bought me my first comic books which proved to be significant. I was lucky to have been exposed to a myriad of things as my father and grandfather had so many different interests. My grandfather had a large book on greek mythology in his office which I loved looking at. My dad had busts of Plato and Socrates in our living room which I unintentionally broke when I was playing with them. I did not understand their significance when I was a child, but ironically, as I got older, I took special interest in their philosophies.

ST:

What prompted your family to move to England? Was there some culture shock at first? In addition to your strong identity as a Nigerian, do you also identify as an Englishman? Can you describe how you manage to balance your dual identities?

RAI:

My father wanted me and my brother to have a better life and a better education. I had been out of school for two years after my father had some business reversals and could not pay the school tuition. My mother had moved to England after my parents divorced when I was about 3 years old . She was born there, had British citizenship so getting us there was rather easy, but there definitely was a culture shock. Most of my ideas about Britain were from television and what we were taught in school – that the British came and made Nigeria better and developed it. The horrors of colonialism and the scramble for Africa was something I only learned about after I left Nigeria. It was also strange to realize that I was the other.

I wouldn't say that I identify as an Englishman even though my father jokingly calls me that when we talk. However, I do identify with Black British culture. I find connections between the diasporic experience and mine as an African. I suppose I have formed a dual identity of sorts, first as a Nigerian and second as a Black man living outside of Africa. I enjoy going to events like the Notting Hill Carnival which celebrates Caribbean heritage and listening to Grime music. Both give me a sense of connection to the UK’s diaspora.

ST:

What sort of education did you receive in Nigeria and what was the level at which you began studying in England? Did you have any early exposure to art in either country?

RAI:

The school system in Nigeria is the same one that the British established: Primary, Secondary and then University. Before I left Nigeria I had completed the Secondary level. A lot of emphasis was placed on mathematics, science and english. I had a difficult time at school. Though no one knew it at the time, I was dyslexic, so certain subjects were difficult to grasp. All the while, I had an affinity for art. I even got in trouble for drawing in class. It was a difficult time. When I arrived in England I had been out of school for two years so I ended up doing a diploma course in business so that I would be eligible to enroll at Central Saint Martins.

In terms of early exposure to art, cartoons on TV in Lagos was a big influence. We had cable so we would get a lot of American shows as well as some Japanese Anime. My father would also buy me comic books as would an older cousin who visited from time to time. I remember one of the first comics he gave me was a Superman anthology, I read it so much that it became tattered to bits. In more formal terms, I had a great art tutor in Lagos during primary and secondary school who would let me bunk classes and go into the art room to make things, He introduced me to a lot of traditional forms of African art including batik dyeing, woodcarving and casting in bronze. This was a blessing because I ended up becoming his assistant. I helped him organise the classroom before our art classes started and helped him after they ended. Besides sports, art was pretty much the only thing I was good at in school. The art room was a safe haven for me when school was otherwise frustrating. When I came to England, I was excited to learn about European Art, Art from Diaspora Artists in the West and Art from other cultures seeing as London was so multicultural.

ST:

What was your experience like at Central St. Martins? What made you decide to study textile design?

RAI:

I learned a lot at Central Saint Martins. I was lucky to have been able to shadow some of the technicians in the print studios during my final year of my Textiles BA. I specialized in Print Design, mostly working with screen printing, Two technicians (June and Dawn) were amazingly generous. They loaned me books and gave me lots of advice. I made friends with students in other departments (Graphics, Fine Art and Fashion) which introduced me to a variety of processes and other ways to be an artist. I chose to study textile design as I was initially interested in fashion and thought that it would be a good career path.

ST:

What made you realize that you wanted to change directions, to be an artist who would make works inspired by your own imagination and agenda, rather than a designer working to create things for a client?

RAI:

I always drew from my imagination even when I was studying textile design. I would reference images here and there but most of my work during that period came from my imagination. After graduating and doing a few internships with textile designers I realised that my future lay elsewhere. During my second year at Central Saint Martins, I was starting to look at textiles as a visual art form rather than a product. That was not a popular view with my tutors, as I neglected certain assignments in favor of doing my own thing. After I graduated, I had an internship where I was tasked with drawing flowers. It was pretty mind-numbing. The next day I gave notice that I was quitting.

ST:

You later earned a Postgraduate degree at The Royal Drawing School? Can you describe that experience?

RAI:

I had been out of CSM for about two years and was looking for a way to reinvent my practice. I learned of the Drawing School while working at an art store and the prospect of drawing for a year sounded right up my street, so after doing some research, I applied and was accepted. Once enrolled, I was introduced to formal and technical aspects from European art history which I found to be incredibly valuable. I especially enjoyed our visits to the National Gallery where we studied and deconstructed old master paintings. I took this class three terms in a row because the treasures at the National Gallery inspired so many ideas for me. I also loved our visits to the National Gallery where, instead of studying paintings, we looked at ancient objects. The idea of drawing something to better understand it was something I had done on my own previously, but these exercises pushed me even further.

The curriculum also greatly expanded my knowledge of European art history. I quickly realized how much I did not know once I got there and spent the year excitedly learning about one artist after another. One project required that we make a presentation on a single artist, someone whose works were readily visible in London so that we could spend time studying, drawing and later discussing their work. I selected William Blake and I am so happy that I did. His emphasis on imagination, spirituality and open-mindedness resonated with me. I love that he railed against slavery in his poems and that he built his own mythology.

Before enrolling, I was mostly drawing in a sketchbook and making slightly larger things on occasion. Having a studio for a year was an incredibly useful experience for it gave me the sense that I could actually have a studio practice and it enabled me to make work that was much larger than a sketchbook. Lastly, the support of the tutors and my peers made this a very joyful experience.

ST:

That takes us to the works in Cosmic Memory. I love that you are developing your practice in a deeply personal way, one that combines figuration and abstraction as well as history and imagination. While you create images that relate to your identity, you also incorporate dynamic abstract elements. Can you describe your motivations in general as well as the intended narrative in a few specific works?

RAI:

In general, I am interested in the collective unconscious and abstract intangible ideas relating to the psyche. I am also interested in reality, history, identity and family, but they are just the starting points for me. I really try to tap into things unseen and unknown.

A few examples might illustrate this:

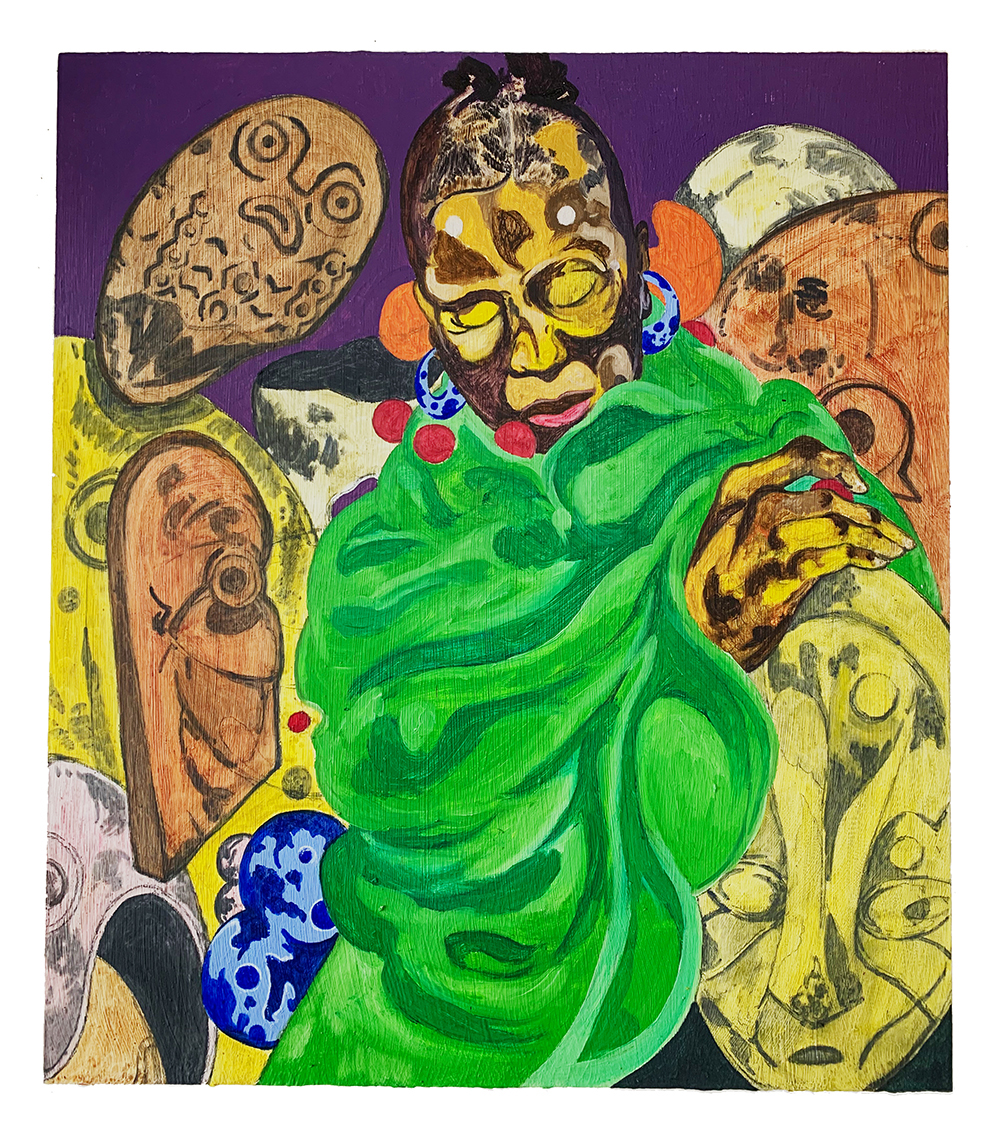

Contemplating with Effigies was inspired by my study of artifacts from various cultures that use effigies for cultural, spiritual and symbolic purposes. I think of effigies as containers of information or objects that possess sacred knowledge. They have survived so that we might engage with them and try to gain some sort of understanding from them.

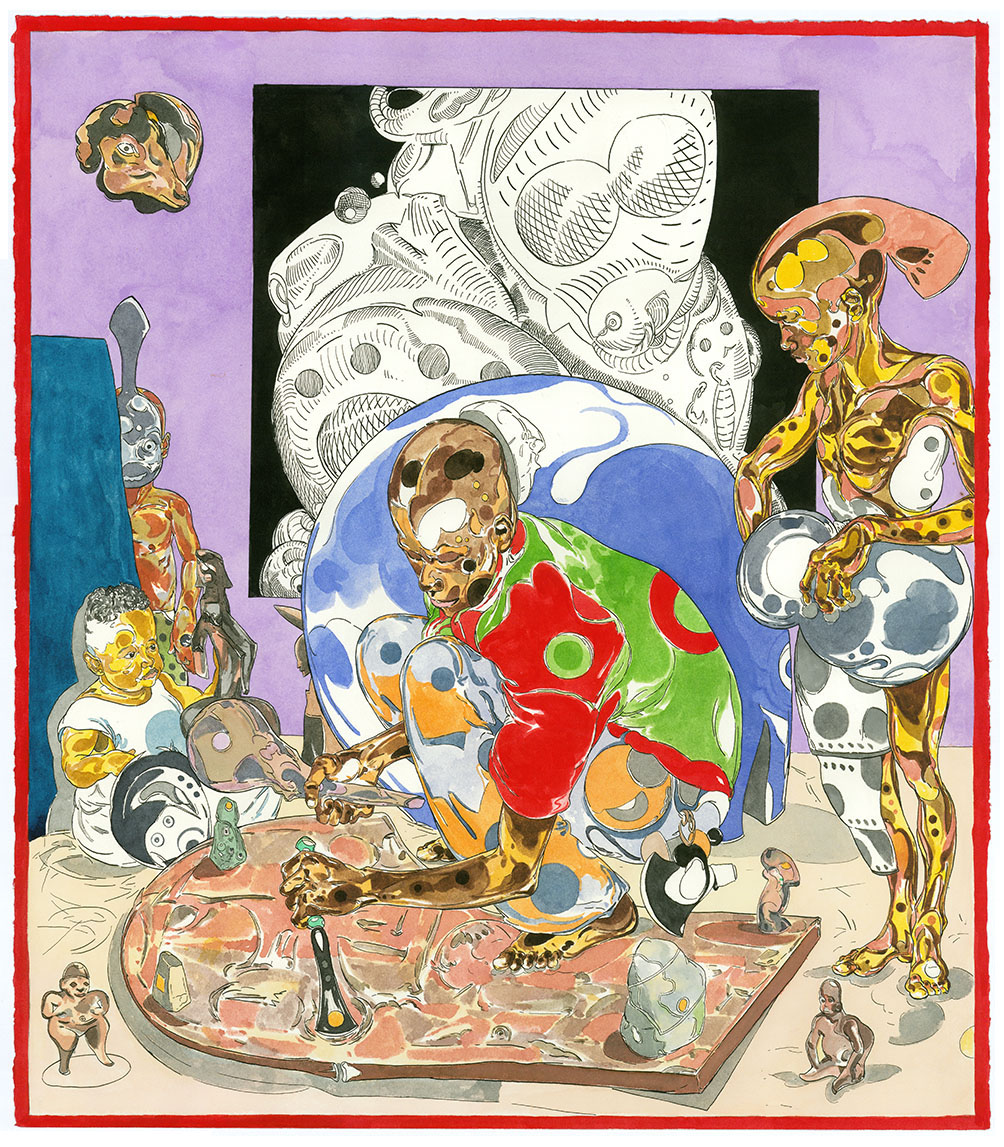

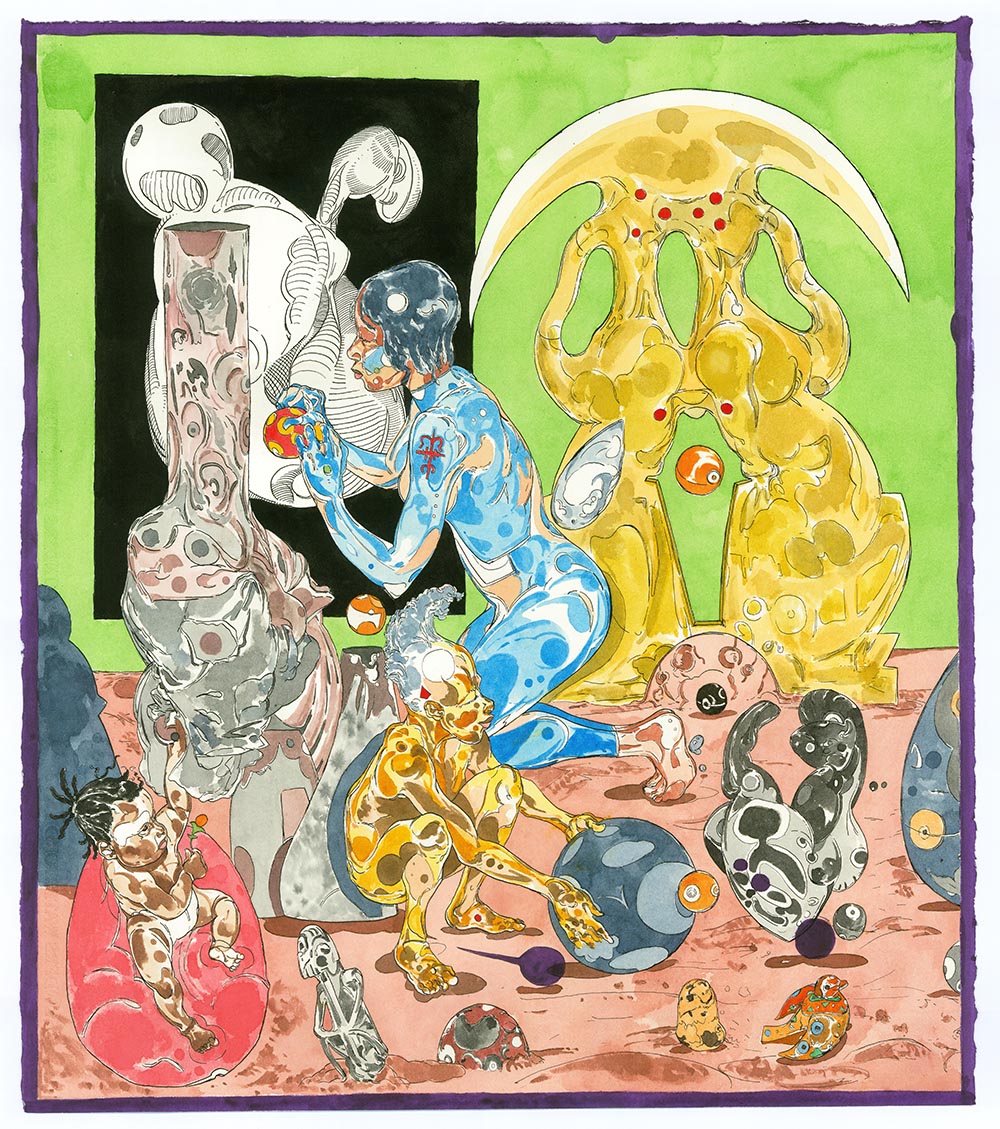

AWÓN OŚERE arose from my study of the role artists have played in certain societies. I know that the artists depicted in this series performed a societal function that is far different from the one performed by contemporary artists. I wanted to imagine their role while I created these works.

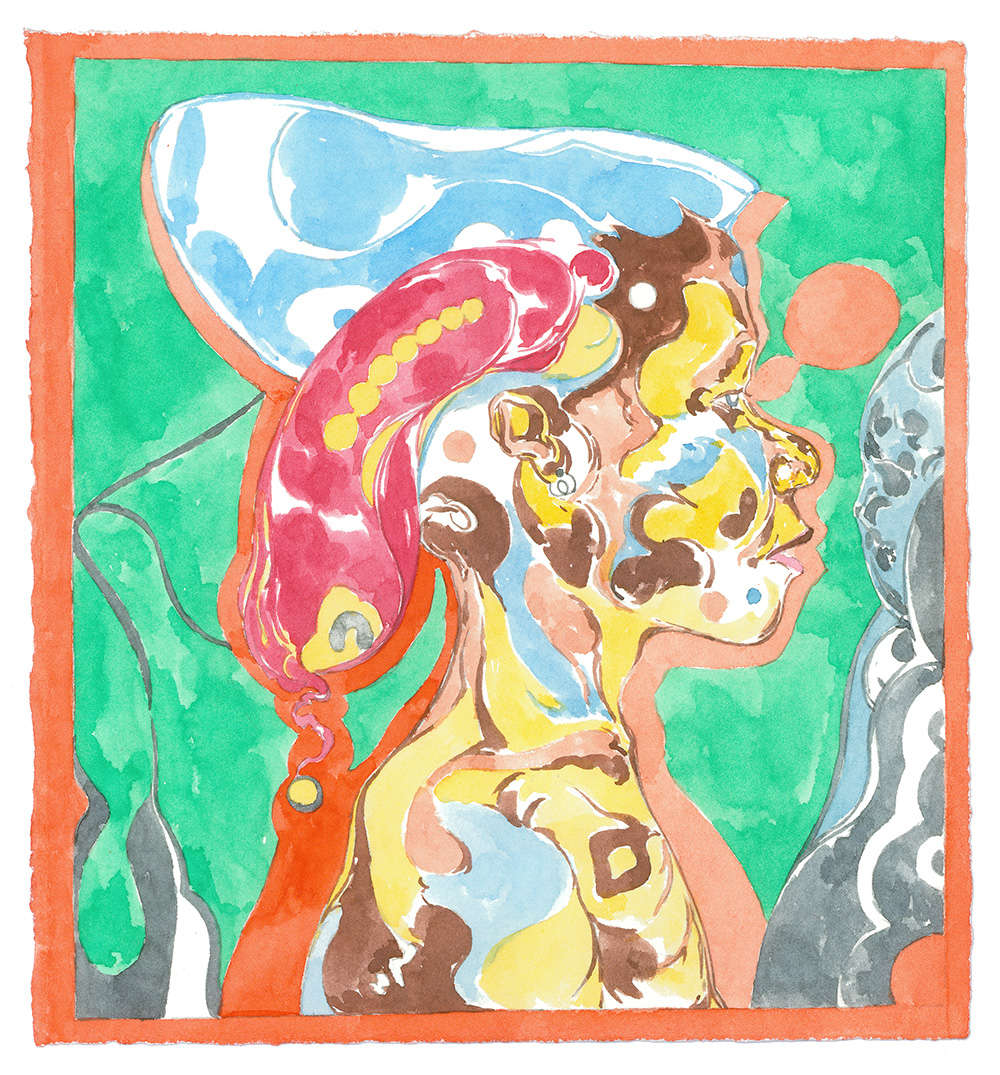

In Future Past Profile 2, I looked to past images in an effort to imagine a future self.