Benjamin Cabral (born 1993, San Diego) earned a BA at Point Loma Nazarene University, San Diego (2016) and an MFA at the Art Institute of Chicago (2019). He has had solo exhibitions with Lauren Powell at SPRING/BREAK, Los Angeles and SPRING/BREAK, New York (2020). This is his first exhibition with Steve Turner.

Benjamin Cabral in conversation with

Aino Frilander, Helsinki-based critic and curator

Aino Frilander:

The new pieces you’re showing at Steve Turner often refer to theater. Can you discuss how theater impacted your life growing up? Were you a theater kid?

Benjamin Cabral:

Theater began as an escape, a way to become someone else and to forget about what was going on in my day-to-day life. A lot of my adolescence was spent in a place of self-hatred. I went to a lot of neuro-development specialists and vision therapists. I had a longing to not be othered but had a brain that insisted on that being my reality.

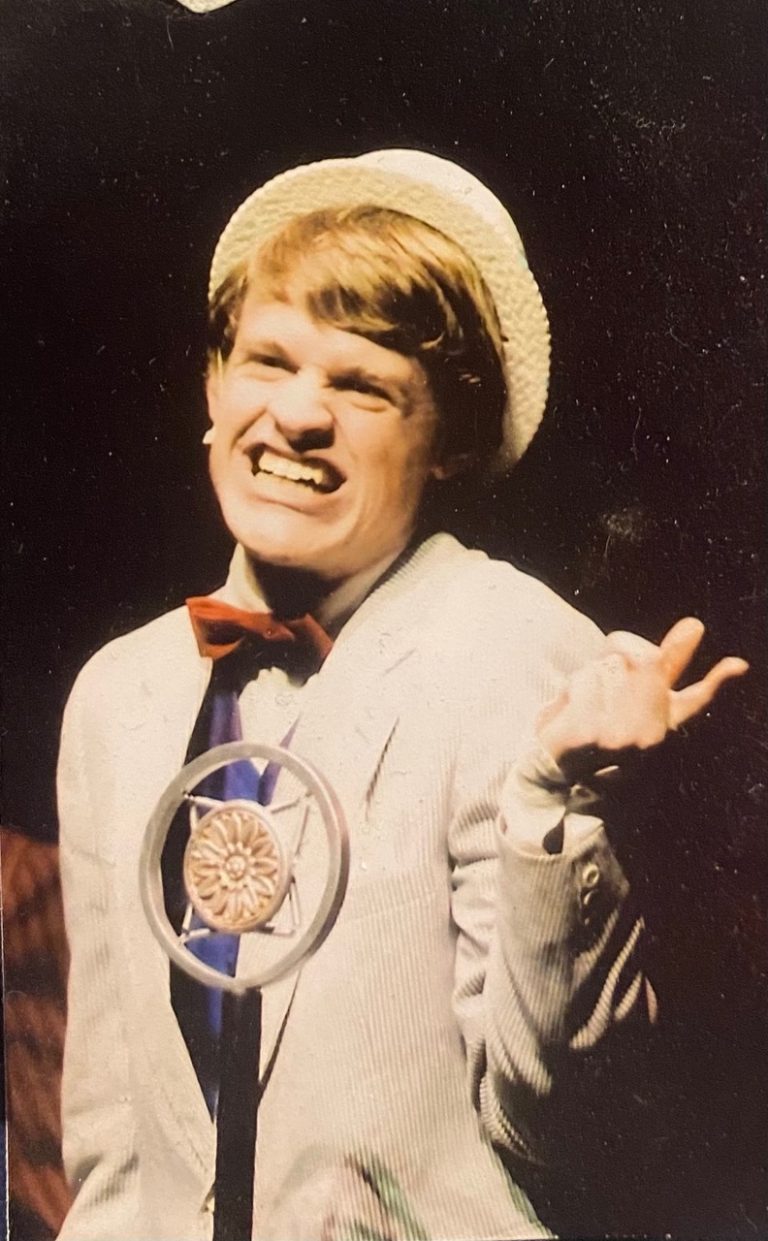

I started performing as a mime when I was nine years old. This made a lot of sense to me as it didn’t rely on words and was unstructured by nature. It also required that I express myself in an exaggerated manner, not directly representing anyone but at the same time representing everyone. In a way, the mime represented what it meant to be human. To this day, I think of this as I compose the figures in my paintings.

Throughout my adolescence and into early adulthood, I continued to participate in local theater clubs. This was separate from my formal education and it was valuable as empathy and performance were rewarded. Performance requires one to tap into their areas of vulnerability but it does not require a complete bearing of one’s soul. There always is a layer of protection because you are still just playing a role.

AF:

When you were getting your MFA at the SAIC, you had a brief “painter’s painter” phase. How did you get over that so quickly? Was there a conversation or a situation that helped you find a new and more natural direction?

BC:

I definitely went through a bit of an identity crisis during my first year at SAIC. For undergrad I went to a small liberal arts university in San Diego. The art classes there were all taught by sculptors who had interdisciplinary practices, so even though I graduated with a visual arts degree with an emphasis in painting, I had never actually taken a painting class. I didn't even know what gesso was until I got to grad school!

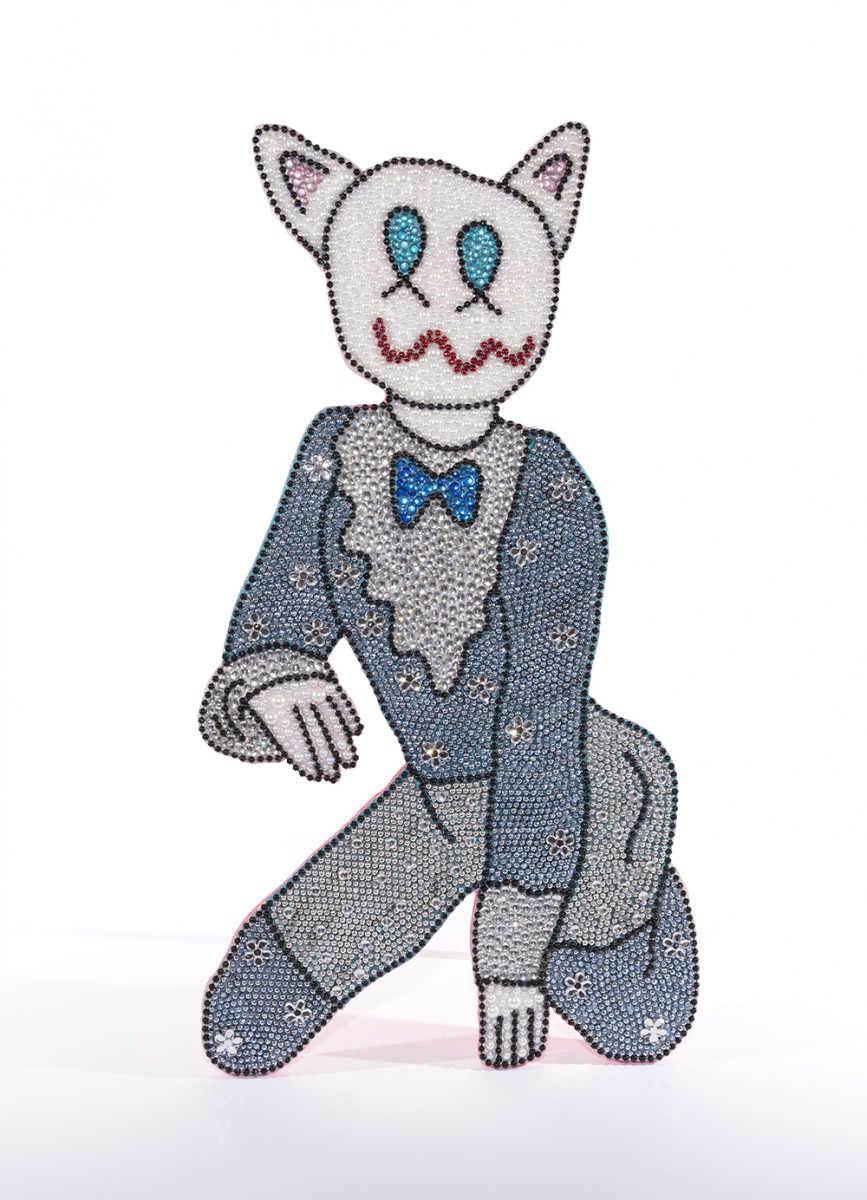

At grad school I was instantly destabilized and thrown into the world of painting, trying to not only learn the techniques but also the language that surrounds it. During the beginning of my first year I painted abstractions but then gradually evolved to paint more representationally. I then took a course taught by Laura Owens and Scott and Tyson Reeder called “What Was Painting”. This class expanded the definition of painting and prompted me to create some large-scale beaded sculpture similar to the one I made for this show. I was excited by these sculptures in a way I hadn’t been with my previous paintings. They felt more honest. When I started making the beaded paintings a lot of the faculty didn’t understand the drastic switch in medium. Though I respected traditional methods of painting, I found it difficult to work that way without being derivative. I felt that everything I wanted to paint had already been painted.

I was totally excited by my new paintings. They enabled me to participate in the long history of painting while also allowing me to create works that felt entirely new. The new process allowed me to meld my subjects with their material and the process. I have always loved making things that required meticulous and time-consuming craft skills, something that I did during my adolescence as a form of therapy. Such work enables me to gain comfort and to cope with difficult situations. In that way, I am able to create a façade of beauty out of memories that are often not beautiful.

AF:

Can you talk about the central character in your pieces, that red-headed boy? Is there an element of self-portrait here?

BC:

That character represents me. The construction of the self is something that continues to motivate me. I'm very interested in the ways in which memory, trauma, and self-identity are linked and inform each other. What interests me most is the inherent unreliability of this construction. How reliable is autobiography? How well can anyone actually know me? How can I even know myself?

AF:

I’m also interested in the bright, childlike imagery that you use. It’s a little bit Carroll Dunham, a little bit Pee Wee Herman, with maybe a touch of this distorted creepy vibe that makes me think of Ryan Trecartin’s and Lizzy Fitch’s videos. Where does that imagery come from?

BC:

I love these connections. When I was twenty I was able to study abroad and go to the 2013 Venice Biennale where I was introduced to the work of Ryan Trecartin and Lizzy Fitch. Their video installations were a revelation for me, and I think that was the moment I knew I wanted to become an artist.

I love how each of these artists creates works that inspire an immediate reaction. My first reaction is joyful, a response to the beautiful colors. Soon after, I realize that the actual subject has a more somber tone, that something is a bit off, a bit dark, a bit sad and even a bit creepy. I find the dissonance to be very compelling and I'm very interested in works that are both dual attractive and repelling. They don’t directly spell things out for the viewer but instead they inspire further consideration. I am interested in “facades of joy” that hide darkness.

AF:

I guess that’s Hollywood and fairytales for you! Brothers Grimm were pretty grim. Your works also often refer to an adolescent trauma, and I suppose your adolescence was overshadowed by your mom’s serious illness. How does that show up in the pieces for you?

BC:

My practice really started in childhood as a way to deal with illness and family tragedy. Growing up I had a lot of neurodevelopmental challenges, and one way of coping with them was to always keep my hands busy. Now they have all kinds of wonderful “fidget” toys for children on the spectrum, but for me I would fidget by creating things with pony beads and doodling on paper.

I also think that there is a constant state of anxiety throughout the work. None of the faces ever really depict a smile or a frown. It is always something in between. For me this encapsulates the fact that even in the most traumatic times emotions aren’t completely binary. In the moments of sorrow hope and joy can be found and vice versa.

AF:

What is your process like?

BC:

I have a nightly drawing practice that is a form of meditation. Basically, I try to create an index of memories through quick iPad sketches. I draw whatever comes to mind in a very speedy manner. I don’t want to spend a long time on each one because I am very interested in the impermanence of memory and the way our memories can often become a construction of our own making, rather than a direct replica of what actually happened.

From these digital sketches I compose my paintings. First I paint my composition in acrylics and then add the beads and rhinestones. I've been experimenting lately with ways to make painted elements more visible, like using clear beads to allow the painterly surface to be viewed. The beads are added one by one, and like the drawing practice, this process is very meditative and therapeutic.

AF:

And why did you end up working with beads and rhinestones?

BC:

I have always loved the aesthetics of bedazzled items–ordinary things that have had sparkle added. I also love people like Dolly Parton, Celine Dion and Cher, larger-than-life personalities that quite literally shine. Fun fact: my biggest collection is of Cher and Celine Dion concert t-shirts. These are pretty much my daily wardrobe. People often expect me to dress in a fashion similar to my work, but I am pretty boring with the way I dress. I just like making other things shiny.

The first time I ever used rhinestones in my work was when I was commissioned by the San Diego Art District to make a public artwork for an outdoor ice-skating rink and holiday market. I initially was using the rhinestones as though they were on a costume–to reflect the light and to illuminate the structure in an interesting way as there was no budget for lighting.

When I started making paintings out of the beads and rhinestones, I did so because I liked the way they hold the light. I also like that the paintings start out as digital drawings on my iPad. While I don’t think they are interesting pieces on their own, I love their illuminated quality on the screen. The beads are really interesting to me because, though they are about as low-tech and craft-based as far as materials go, when lit they have an aura that reminds me of the screen. I also like how the beads are reminiscent of pixels on the screen.

AF:

I envy your shirt collection! I also like the combination your imagery–red thigh-high boots, bare-chested men in suspenders and whatnot–with the sparkly beading. The works have a touch of fabulousness and campiness to them. Does that idea make sense to you? What does fabulousness mean for you?

BC:

Fabulousness and camp are definitely important elements in my work. I think these ideas come with a sense of freedom that can be beautiful and liberating. I sometimes think of the work as similar to drag, a beautiful and performative exterior that allows me to play with conceptions of masculinity. I also like to play with the canon of “white male art” and push back at its associated aesthetics. With drag audiences can see an amazing performance but not take it as seriously because it is a drag performance. I think audiences might react similarly when they see my paintings performing in drag.

AF:

You mention protection, and I did get the feeling that the beading also makes for a hard, nubby protective surface especially in the pieces that make reference to moments of vulnerability and anxiety. What do the beads protect?

BC:

I think in the most literal sense the beads protect the painting that is underneath them. Art is a career where generosity is a requirement, not a choice. The artist is continually asked to bare their soul on the canvas without receiving a reciprocated vulnerability from the audience. It’s an unstable relationship that sometimes can make me feel slightly uncomfortable as I allow people into the memories I hold dear as well as the traumas that I carry.

Having a piece of the painting that exists for me only is something that I find special. I sometimes almost think of the beads like a Band-Aid. The painting is the wound that the viewer knows exists, but the beads are like a beautiful Hello Kitty Band-Aid that not only protects the wound but also makes it more visually pleasing.

Click here to view Benjamin Cabral's solo exhibition, Soliloquy for Past Futures

Please direct inquiries to

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.a