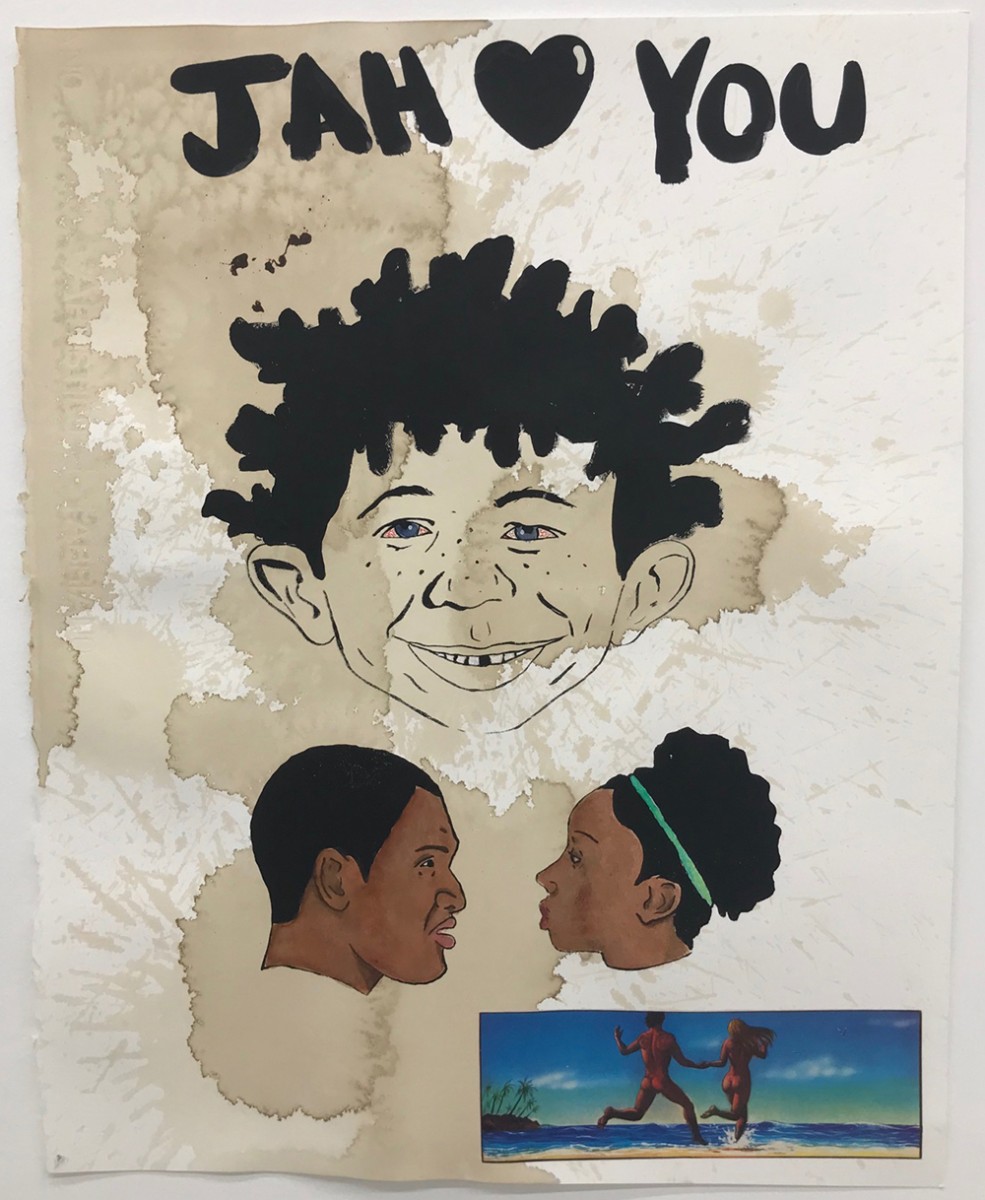

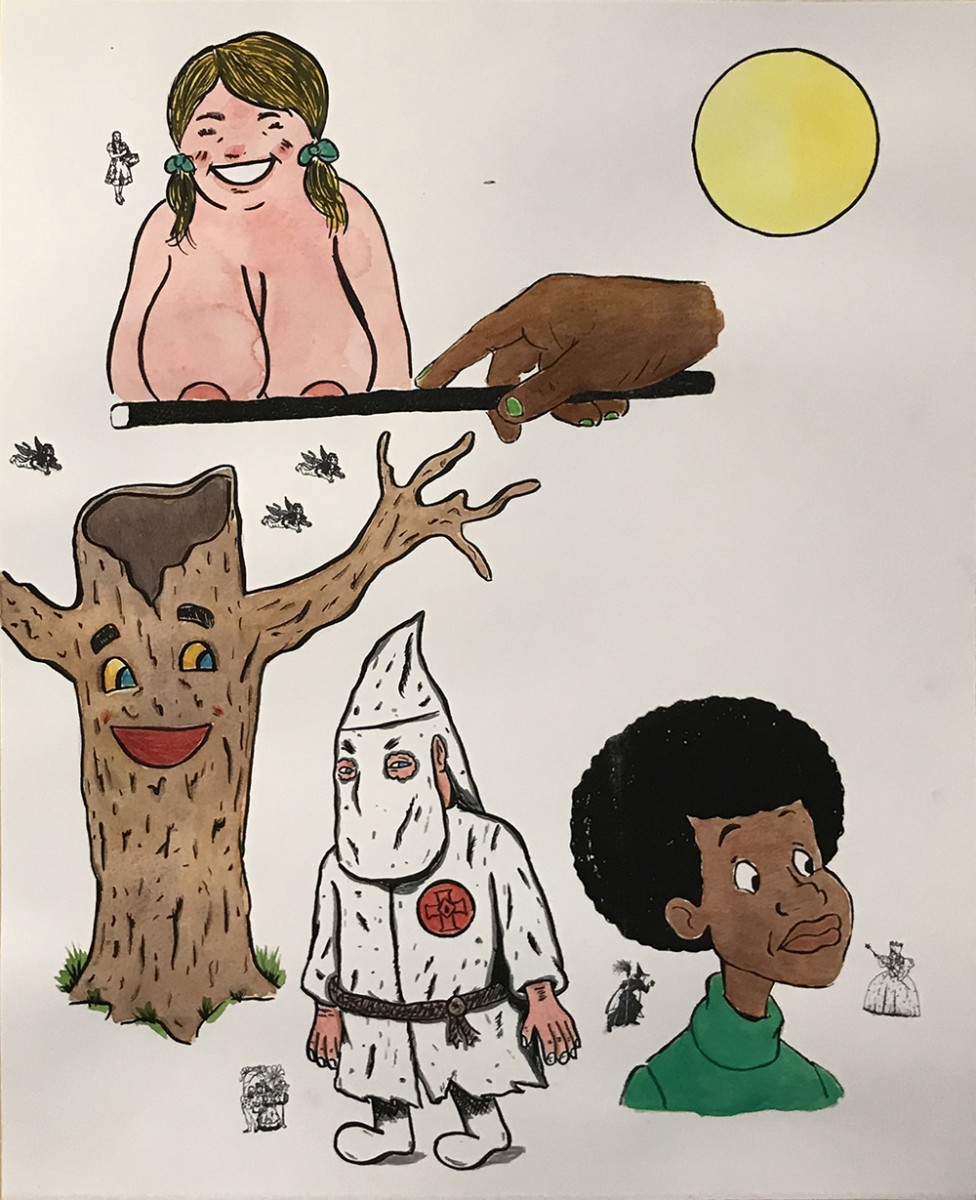

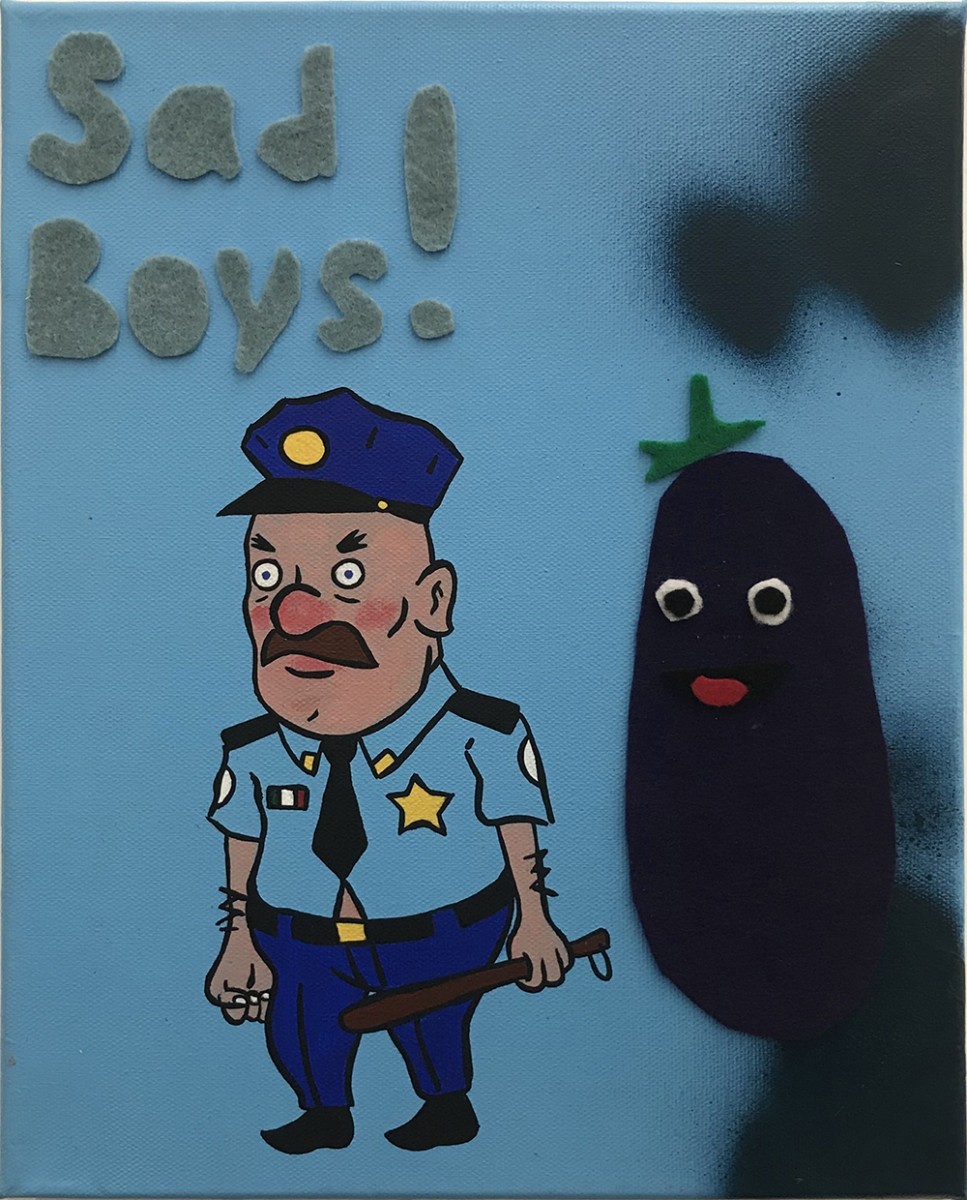

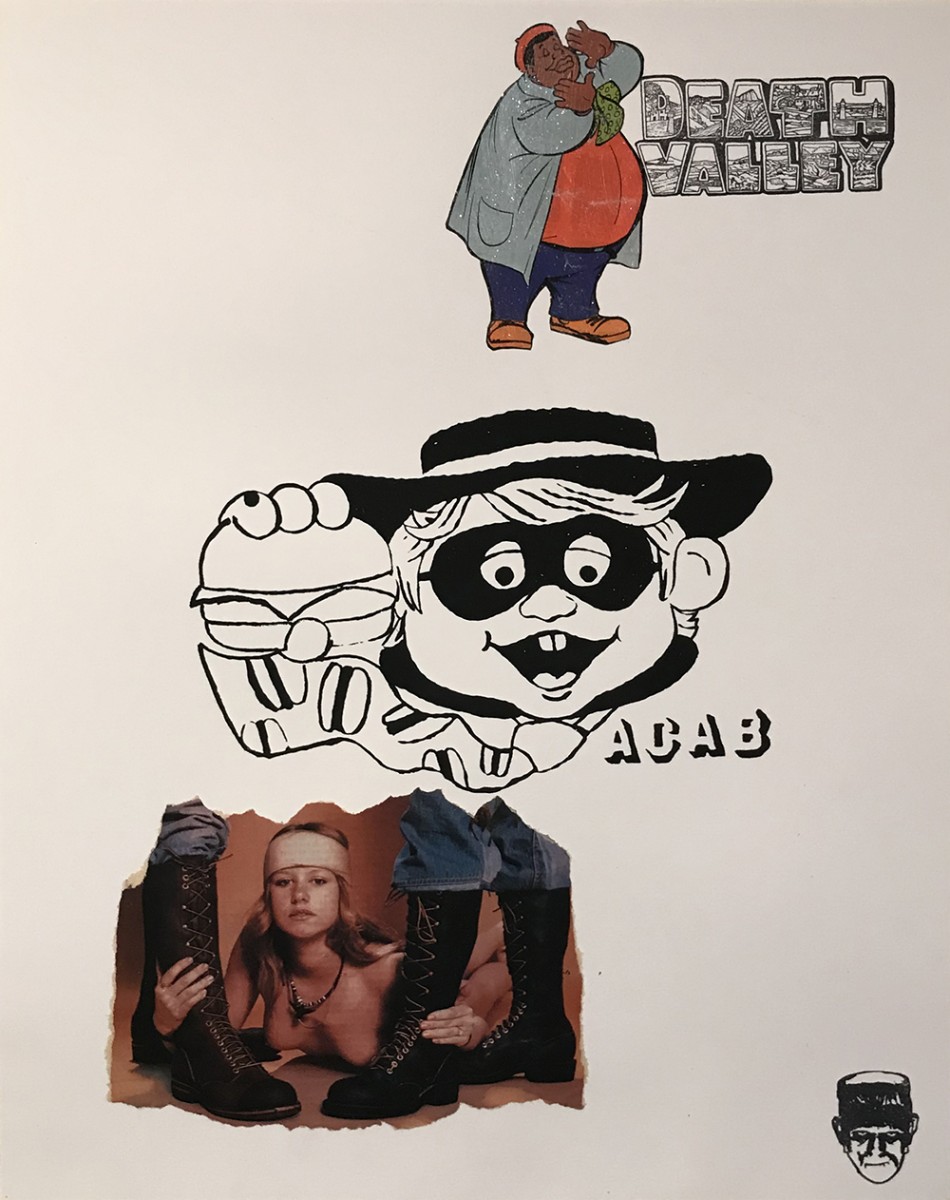

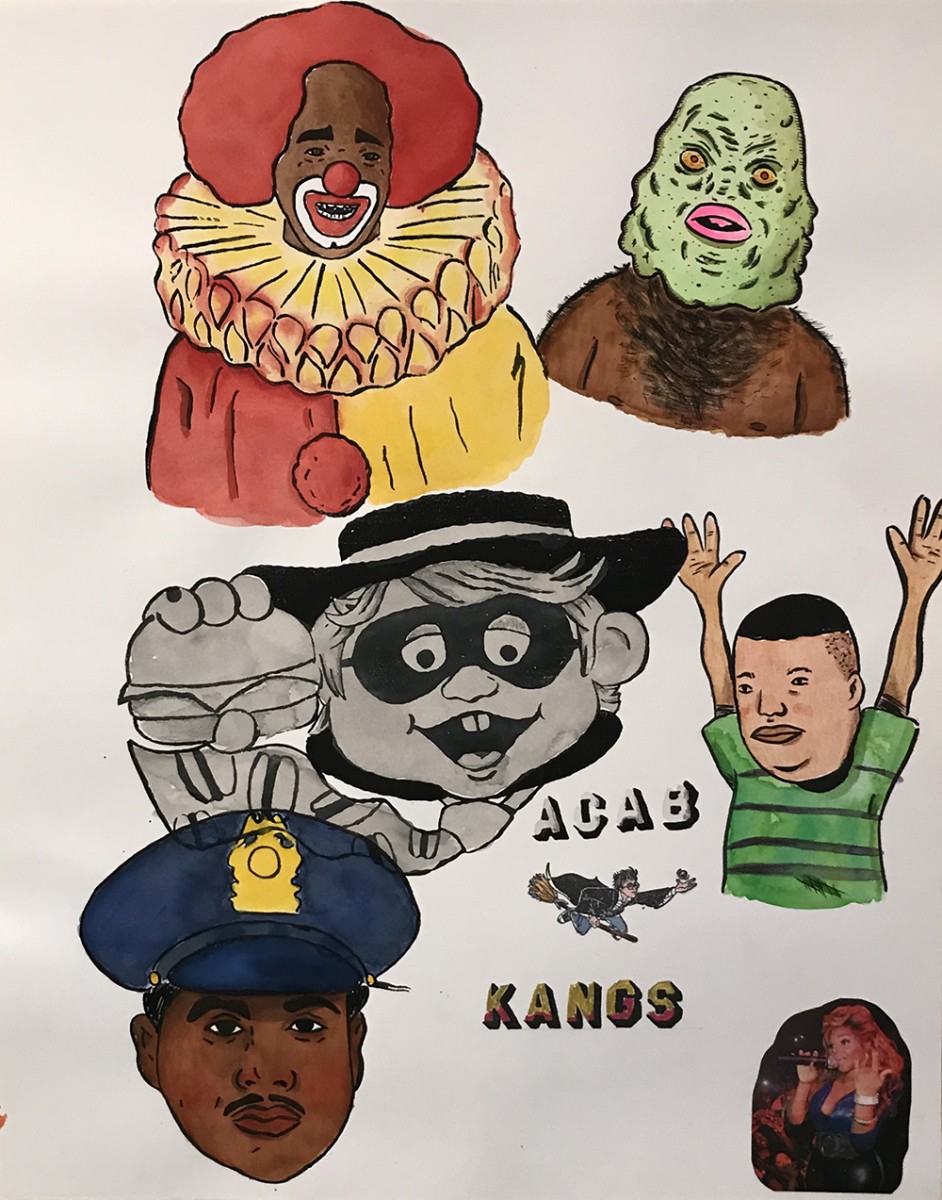

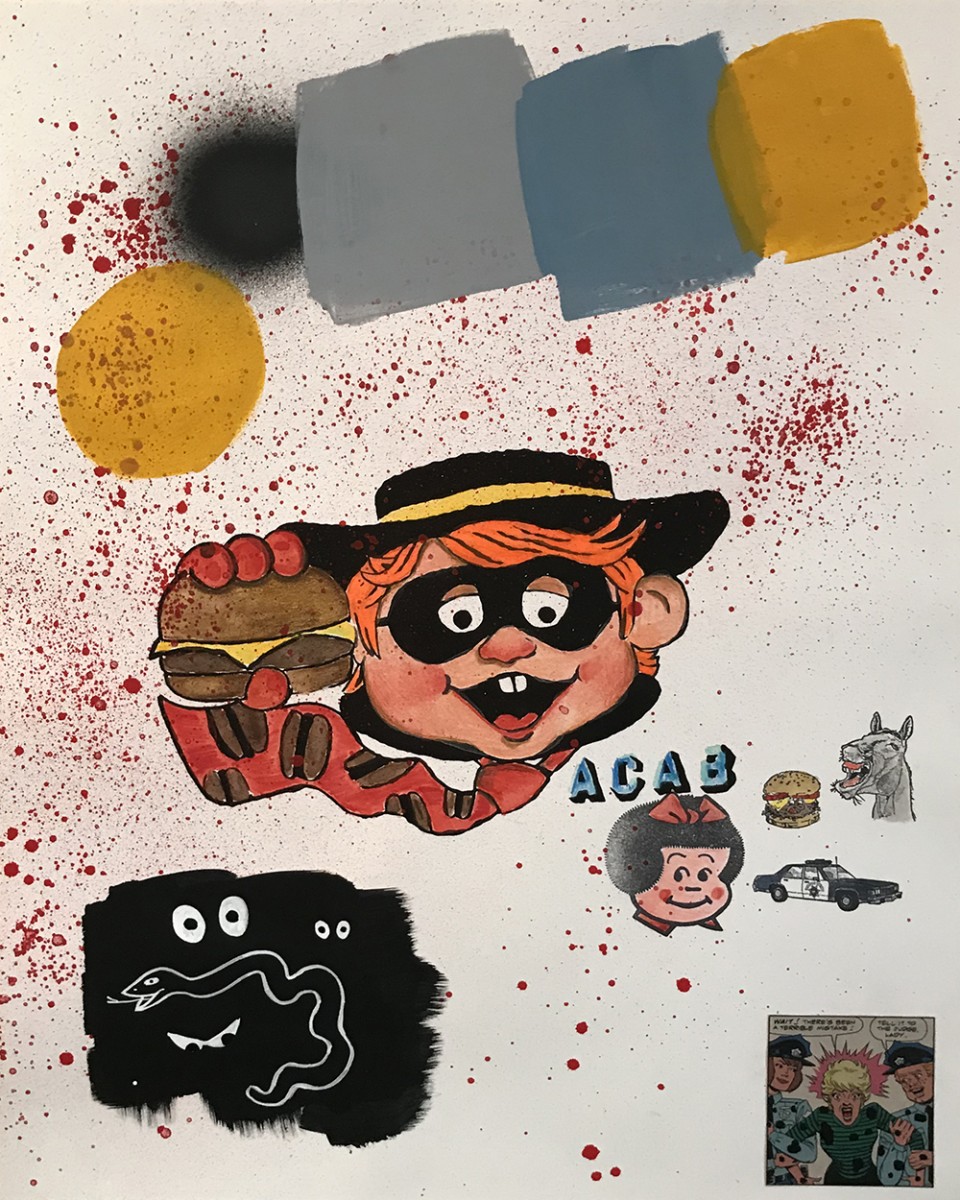

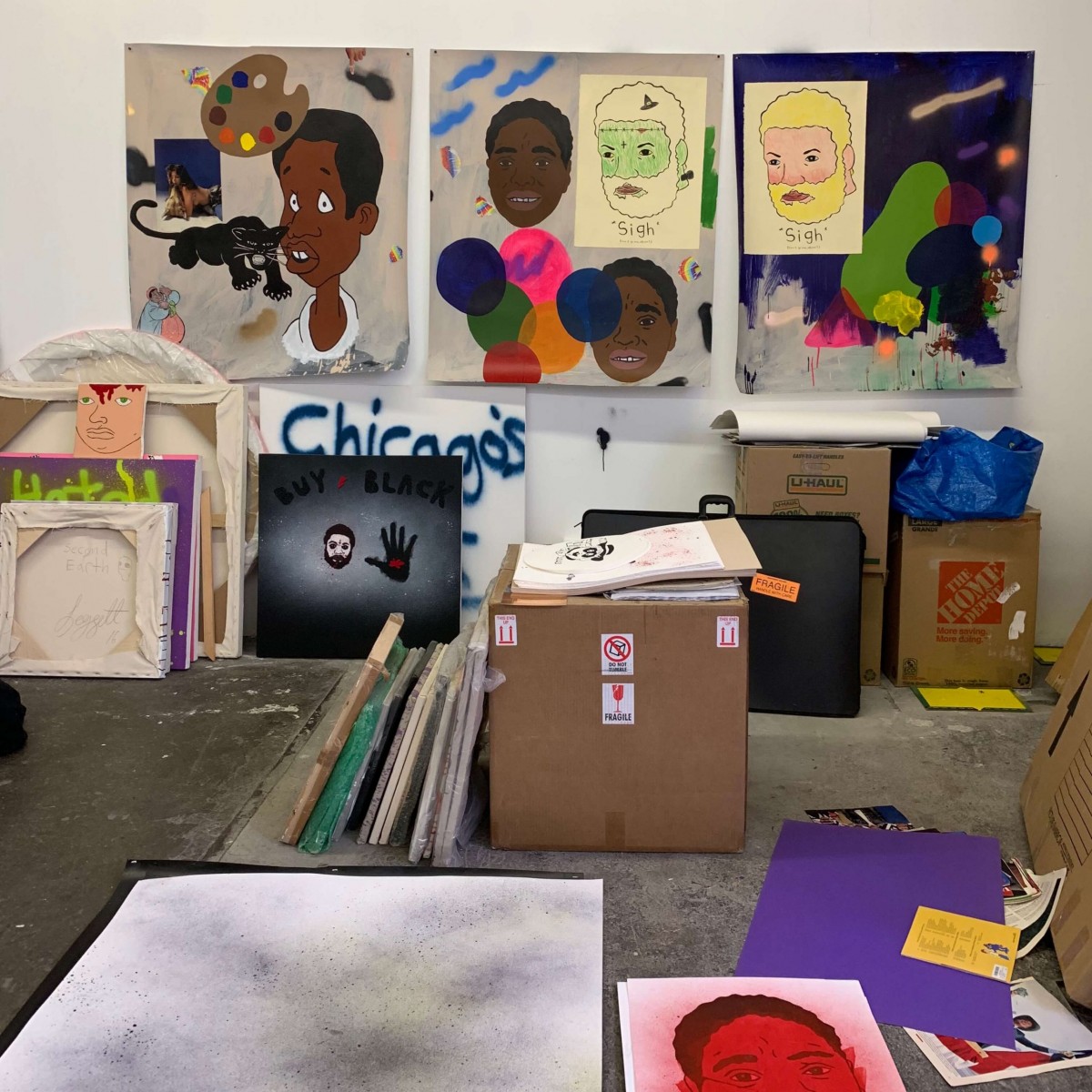

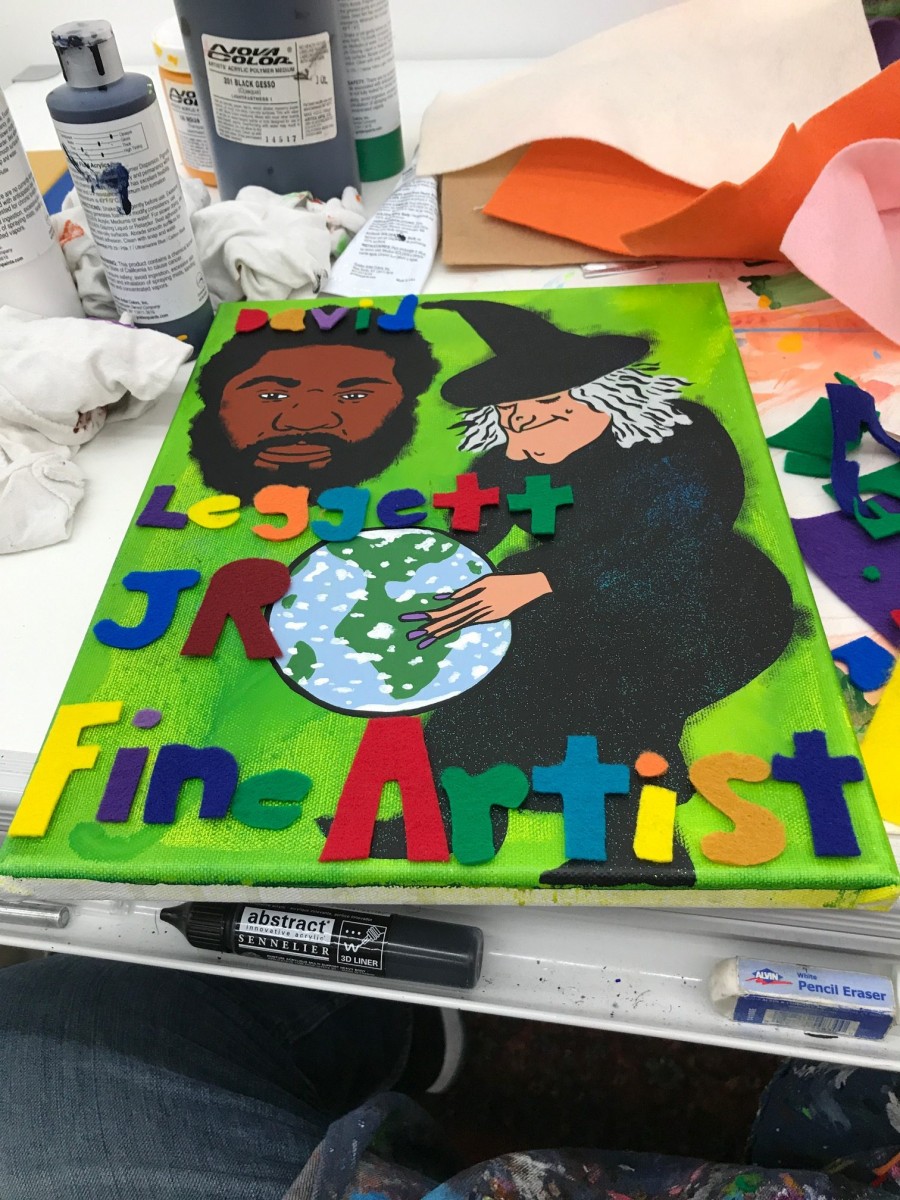

David Leggett creates paintings and drawings that utilize a comic style to deal with serious and sensitive subjects like religion and racial injustice. While he makes his works accessible with colorful depictions of Bart Simpson, Mickey Mouse, clowns or other somewhat familiar blobby characters coupled with catchy phrases, he does so to get you in. Once there, you will have to face the more difficult issues that are part of every work. In doing so, Leggett broaches subjects that are often too difficult for most artists to address, or when they do, they do so in a heavy handed, cliché laden manner that has no effect. Leggett’s approach is successful because it does not tell you what to think, but it does ask you to think.

David (born 1980) earned a BFA at Savannah College of Art and Design (2003) and an MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2007) before attending Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2010). He has had solo exhibitions at Shane Campbell Gallery, Chicago (2017 & 2019) and his work has been included in group exhibitions at Zidoun & Bossuyt Gallery, Luxembourg; James Fuentes Gallery, New York; Kunstverein Langenhagen, Germany and the Contemporary Art Museum, Raleigh, North Carolina. Leggett's debut solo exhibition at Steve Turner, Los Angeles, Why you really mad? was on view through July 18, 2020.

David Leggett in conversation with

Aino Frilander, Helsinki-based critic & curator.

Aino Frilander:

The visual world of your work is very specific – classic animation, 1970's and 1980’s comics and cartoons, magazine cutouts and crafts. A lot of it reminds me of my early childhood in the 1980’s. Is that visual world something that stems from your school days, or does it come from somewhere else?

David Leggett:

The images I use in my work come from many sources. I’m interested in older illustration, animation, Black Americana and comic books. Some of the images are older, from the early 1900's to the 1960’s. I like using images from that time period because many have been softened for today's standards. In recent weeks some companies have opted to remove some of these images from their products.

AF:

What interests you in that process of softening?

DL:

Most companies had mascots for their products in the early years of advertising. Several companies have or had caricatures of Black people as those mascots. Often they were portrayed as servants. Over the decades these mascots were either phased out or they were made less stereotypical. It’s interesting how a race of people could be subjugated and yet their likeness be used to sell products to white people. In the early advertisements they were portrayed as very meek and docile. Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben being phased out is especially interesting to me. I have collected early ephemera of the products and I’m surprised that it took this long.

AF:

What about the comic books, which ones were an influence? If you would give me a tour of your bedroom in 7th grade, what would it look like?

DL:

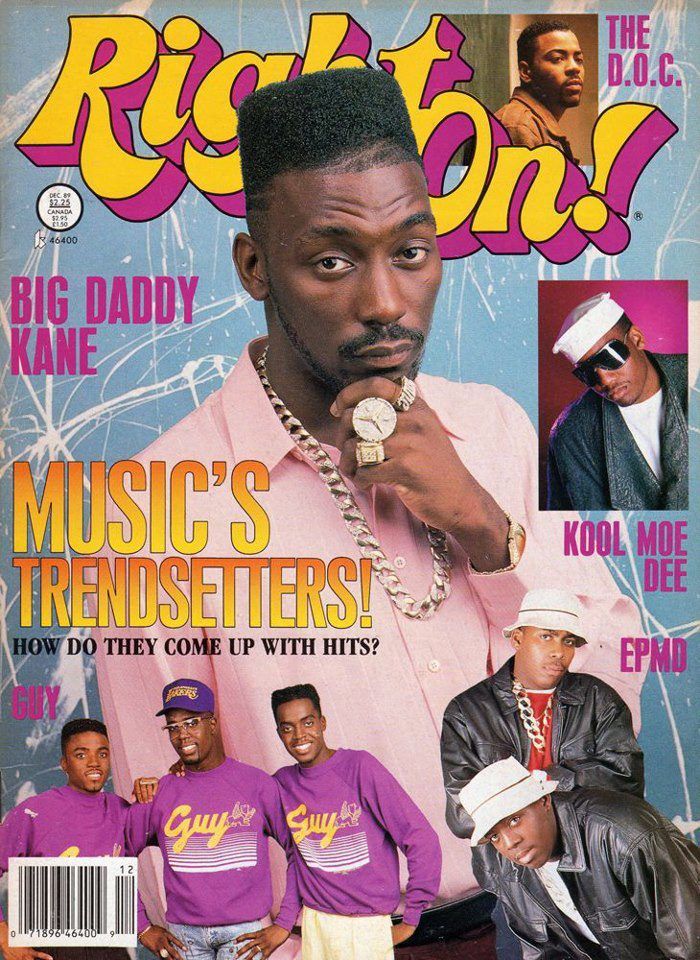

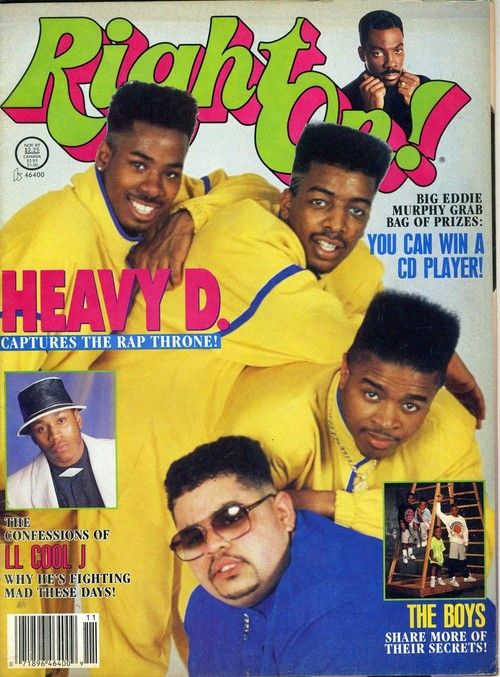

I collected Marvel and DC comic books from age five until I was nineteen. I was mostly into Spiderman and X-Men. As I got older I got really into Image Comics. I was big into Spawn and then Preacher from DC Vertigo Comics. Around 16 I started reading underground comics from Peter Bagge to R. Crumb. The walls of my room were covered in comic posters from Wizard Magazine and hip hop posters from Word Up and Right On Magazines. I think the hip hop posters had a bigger influence on me and my use of graphics. I really liked Mad Magazine at the time as well. Mad made fun of everyone and I loved that as a young child.

AF:

Hahah. What were you like as a kid? Did you channel your mischievousness into reading Mad magazines or were you a little bad yourself??

DL:

I was a quiet kid. I mostly kept to myself. Mad magazine made fun of adults and at the time that seemed so cool. I would try to use some of the jokes from the magazine with my classmates. They always fail flat. I guess I had a terrible delivery.

AF:

Aw, I know, I’ve been there! But I feel like your delivery works a lot better in your art practice, if you don’t mind a kind of a cheesy transition! I love the one-two punch of your work – first the color and the pop culture imagery draws you in, and on a closer look you find yourself asking yourself some pretty serious questions about gender and race. How did you develop this strategy?

DL:

That is something that took time to develop. I’ve always focused on hard, difficult subject matter. I had a lot of push-back from my classmates and professors at times. Often I felt misunderstood.

AF:

Like when?

DL:

When I made work that dealt with homophobia, racism or class. I understand now why. People were turned off by how I was delivering the message. It was much more in your face. I was trying too hard. I would get my ass handed to me as a result in critiques. I had to figure out a strategy in order to bring people in and not turn them away. I also leave the subject matter open for interpretation. By doing so the viewer has to make up their own mind. They may laugh at something and then be horrified that they laughed a minute later. They may question their own values.

AF:

I recall reading that you said you wanted to make the kind of art that your dad would get.

DL:

When my father passed away in late 2015 I had a moment where I wanted him to be able to engage with my art if he would still have been alive. My father was a hard-working blue-collar man who didn’t know anything about fine art. I tried to focus on making my ideas clearer and using more familiar imagery to make my work with the hope that he would understand, as well as anyone else who may not be interested in art.

AF:

You say a moment – is that still something you’re trying to do?

DL:

This is something I’m still working on. I think this is a good problem to have and it will never be solved.

AF:

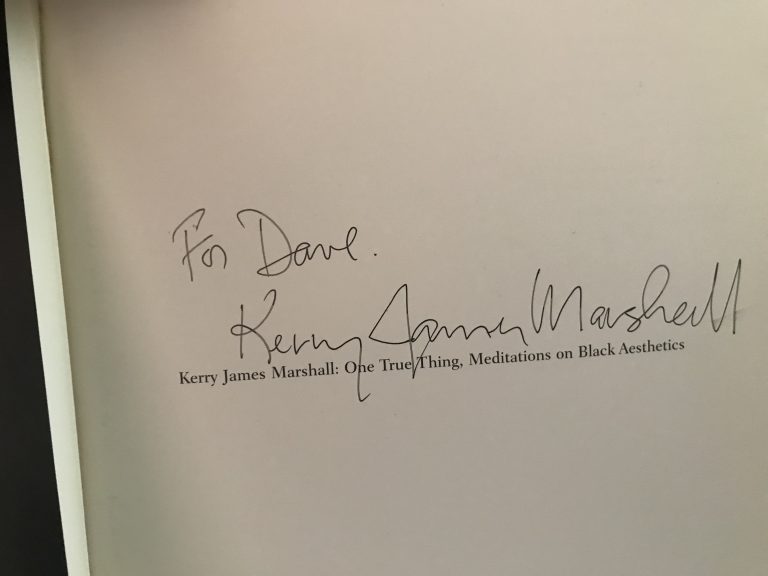

I think you’ve said that Kerry James Marshall was one of the reasons why you originally moved from Savannah to Chicago. Can you take us back to that moment and talk about what in his work spoke to you that strongly? I guess I’m basically asking you to just talk about how great he is!

DL:

At the time I had not seen too much contemporary black figurative art. It was mind-blowing to see his work when I was in my early twenties. The year I moved to Chicago, Kerry had a solo show up at the MCA and there was work of his up at the Chicago Cultural Center. I couldn’t believe the scale of the work and his handling of materials. His work was unapologetically Black and stood on its own. He was still teaching at the time I moved to Chicago. I was hoping to sit in on one of his classes even though I went to a different school.

AF:

I love that! Did that ever work out?

DL:

I never sat in on a class, but I met Kerry the second month I was in Chicago. I went to his artist talk at the MCA. I got my catalog signed. I had so many things planned to say to him as I was standing in line waiting, but by time I got to him I chickened out and said, “I enjoy your work”. That is all I could get out. I’ve bumped into Kerry a few times after that throughout the years in Chicago. He’s a nice guy.

AF:

Hahah. That’s very relatable. Giving compliments to giants is hard! How do you think your work relates to his, if at all?

DL:

We work with narratives on Black life. He is a master at what he does.

AF:

You moved fairly recently from Chicago to Los Angeles. What was your experience of Chicago like?

DL:

Chicago is a great city. I wanted to work with The Chicago Imagists after I read about them in an art history book. It’s easy to look them up now, but back in 2000 it was pretty impossible. I enjoyed their use of color, pop culture and subculture. In Chicago I developed my practice in alternative spaces and group shows with friends. Chicago at the time had many apartment galleries and alternative spaces. It was a great way to show your work even if only five people saw the show.

AF:

That sounds so great! In which places did you show and which spaces did you love going to?

DL:

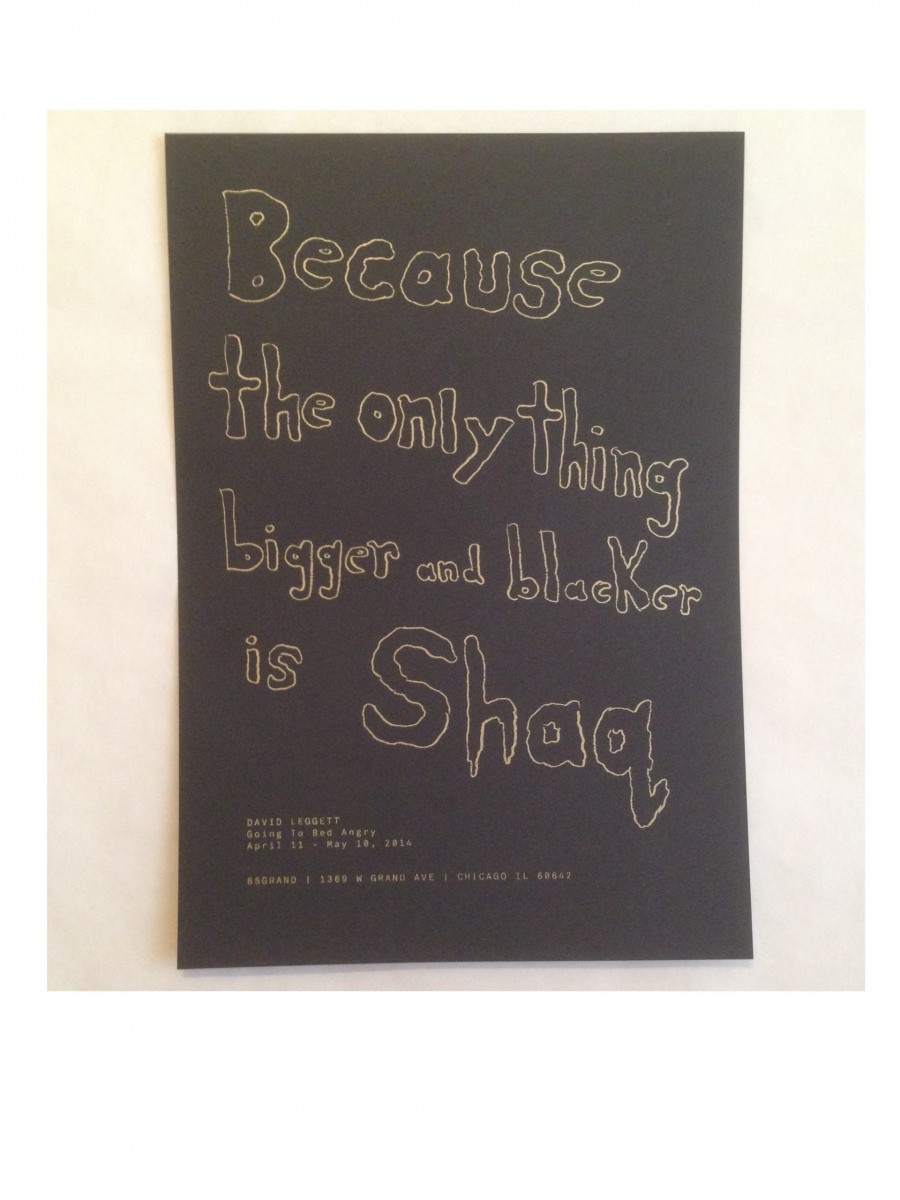

I wanted to show at the Hyde Park Art Center because The Hairy Who and many other Chicago Imagists had shown there. I had a solo show there in 2012. Many of the apartment galleries are no longer in existence. My favorite apartment gallery was 65 Grand Gallery. I had my first solo there and showed there twice.

AF:

But you ended up in LA?

DL:

I never planned to live in Chicago for as long as I did. I originally intended to move to New York years ago. After visiting Los Angeles on vacation, I thought it would be a good place to move to. Los Angeles has a great art scene. There is so much to see. LA is different from every other place I lived. I’m still getting used to small things like traffic and talking to people here.

AF:

Is there something special about talking to LA people??

DL:

I realized how aggressive I can talk since I got here. I was raised in Massachusetts and everyone talked that way, and so did most of the people in the Northeast. People out here are more mellow and laid back.

AF:

How do you feel about the current moment we’re living through in terms of Black Lives Matters protests? What sort of a role do artists have in the movement?

DL:

My parents were active in the civil rights movement when they were young and taught me and my sisters about protesting. I have a lot of hope for the BLM movement. I’m glad to see a new generation engaging one another. I’m not sure what is the artist's role in the movement. If you’re an artist and you choose to engage in the movement, that is great, and if you choose not to, that is also fine. If you are an artist and you are now newly engaged in being an activist, be aware that there have been people at the front lines of these issues before you and you can learn from them.

AF:

I feel that your work deals with the question of race with a lot of humor, but it also feels that as a society we’re kind of past humor right now and people are mostly very tired, frustrated and angry. Do those feelings have a place in your work?

DL:

I feel humor is always needed and is one of the things that connects us as human beings. Injustice is not a new thing. Dick Gregory was very active in the civil rights movement and had many jokes about current events of the day. Richard Pryor had jokes about police brutality and was interviewed more than once about that topic. Those jokes gave people who normally never see such acts a glimpse of it, but also let people who knew police brutality all too well know that they were seen and had a voice. Black people have used humor throughout the years to ease pain, and that has not changed. In my work I have dealt with racism for years. I’m not interested in making misery porn art. I’m letting the viewer decide what to take from the work, but I also know the Black audience will understand my references more and appreciate the humor.