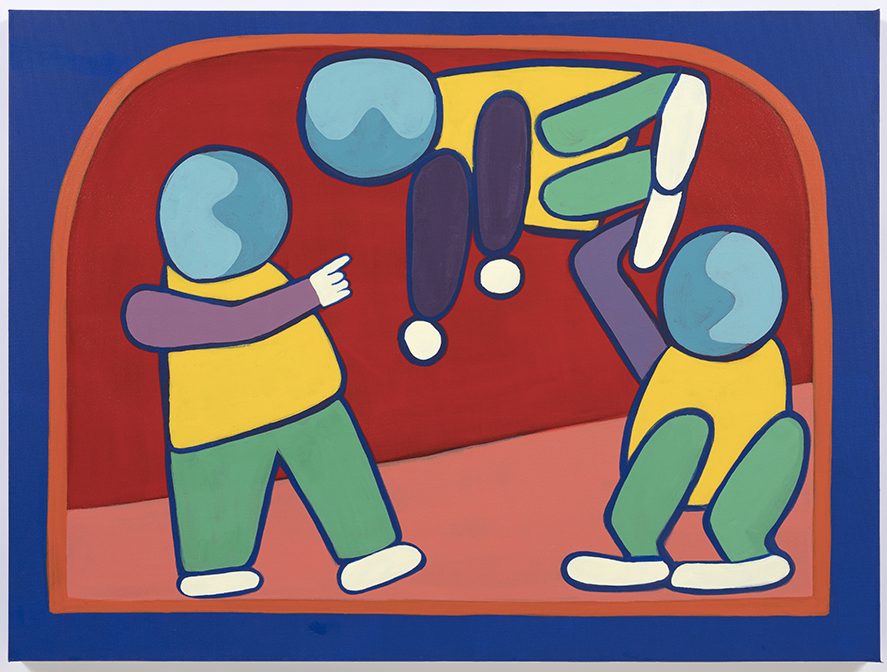

GABBY ROSENBERG (born 1992, Chicago) creates paintings that encompass both representation and abstraction. Some lean one way, some the other, but all include rich color compositions, carefully chosen for the way individual colors relate to others. These relationships, which sometimes have sharp contrast and other times subtle contrast, are central to Rosenberg’s compositions. To the extent that figuration is depicted, Rosenberg presents gender-ambiguous figures that are part self and part monster. Many have fragmented body parts that are stacked in concentric circles. These blobby characters are often depicted with exposed joints or innards, a suggestion of vulnerability. They represent a visceral feeling of otherness and the complex fluidity of identity. Rosenberg also acknowledges a debt to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein with its creature’s desire for intimacy.

Gabby Rosenberg

&

Alexandre Saden in conversation

Alexandre Saden

I imagine the reality of living in Los Angeles right now amid fires and a pandemic must be at the forefront of your mind, but I would like to start at the beginning: what is your background? Where and how did you grow up?

Gabby Rosenberg

Yes, both are very much at the forefront of my mind. It has been an unrelenting couple of months navigating the pandemic and the very tangible confrontations with our climate crisis. I am incredibly thankful for the health and safety of my friends and family, and have a deeper appreciation for blue sky and clean air.

I grew up in Evanston Illinois, just outside of Chicago. Both of my parents are artists, so when I was young it felt like art was very much their thing and I had a hard time engaging with it. In my second semester of undergraduate studies, out of curiosity I enrolled in a drawing course and it sparked something in me. Art then became the focus of my studies. I started painting soon after. I had experimented with other mediums, but nothing came close to my infatuation with color and paint. After graduating, I moved to New York and had a handful of odd jobs so that I could still have enough time in my schedule to paint. After getting into CalArts I deferred for a year so that I could figure out how I was going to move across the country and uproot my life. Five years later, I am very happy that I did just that.

AS

It sounds like you always saw yourself as a painter. Was there ever an alternative path?

GR

I have wanted to be a painter since the early stages of my undergraduate studies. When I got to college I initially thought I was going to study policy or psychology. I also took a bunch of film classes, and then thought I could bridge them to painting, but it never worked out. Painting was always more enjoyable and interesting to me. Since that one drawing course, being a painter has been my objective.

AS

How do you start a work? I have watched you paint for a long time, and I’m always amazed by how decisive you are — do you have a plan in mind before the first brushstroke?

GR

It is a bit of both. I usually have a general idea of what the composition of any given painting might look like, or how many figures I want to include, or what kind of interaction I want to depict. On the other hand, my color palette is a bit more improvised. I may go into a painting knowing broadly that I want to work predominantly with specific colors — black and yellow for one, red and blue in another — but I don’t know exactly how they’ll interact until I get them down on the canvas. I often start with a tonal underpainting to achieve texture and dimension in the background. I then build from there, observing and playing with the ways each color reacts to another. I make sure to have different marks and brushstrokes throughout the work. I want the viewer to look everywhere. If I don’t like the result I often restart. I will paint over a painting until I get it exactly where I want it to be.

AS

What did your paintings look like early on? Were you always a figurative painter?

GR

My paintings used to be more minimalist — in some instances, there would be only two colors in a work. I would place restrictions on myself, such as time limits, paring down my pallet, and painting with a limited number of tools. I was more focused on the strokes, or the colors, occupying as much space as a figure would. Slowly, I began painting abstract fragmented body parts. I was particularly interested in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein monster and the way he came to be, through fragmented parts of both animal and human flesh. The monster’s frustrations, his desire for intimacy, and his ultimate quest for a body that makes sense makes him the most relatable monster. This narrative illustrates that a body that doesn’t cohere and that is misrecognized can attempt to exist in society. This is a feeling I have constantly tried to develop in my work.

AS

What was your first encounter with Frankenstein? Do you have a personal connection to the figure or more of a theoretical one?

GR

My first encounter with Frankenstein was through a class I took at CalArts with the Los Angeles-based artist Candince Lin. In “Monster, Witches and Exhumans” we looked at “Skin Shows” by Jack Halberstam which suggests that monsters are defined by the stereotypes placed on them by those who deem them to be “others.” Frankenstein’s monster became the symbol that I wanted to represent. I would create abstracted body parts that didn’t fit together: partial limbs, joints, muscles and fat smashed together to create a “monster.” Initially my connection to Frankenstein was theoretical, a way for me to bridge these ideas into what I was painting. Now it feels incredibly personal, because I have spent so much time painting this “monster.” In the new Icons series I have a painting titled Red Frankenstein.

"The figures tend to be gender ambiguous. Some are loosely based on me or on friends."

AS

Tell me more about the figures that populate your work. Who are they? Is it correct to call them figures?

GR

The characters in my recent work are the most figurative that I have made in a long time. Prior to Icons, I would often take chunks of different colors of paint, slab them on the canvas using various tools (brushes, palette knives, sponges, etc.) and then connect the colors to one another with regard to size, shape, and texture. I considered those arrangements to be figures as well.

The figures tend to be gender ambiguous. Some are loosely based on me or on friends. They experience a range of emotions, engage in different activities, and some interact with one another. In my work, and in my relationship to these figures, I am trying to convey feelings of vulnerability and otherness–the physical experience of being in a body. So yes, I would say it is correct to call them figures. But I have a very broad view of what can be considered a figure.

"In my work, and in my relationship to these figures, I am trying to convey feelings of vulnerability and otherness–the physical experience of being in a body. "

AS

You mentioned this body of work is a series, Icons — is it fair to say that your work is composed of distinct series?

GR

Yes, I think so. That said, I think that the series are very much related to one another, with each new series building upon the last. The characters in Icons are born out of the colorful lump figures, which were born out of the exposed joints and innards. In this series I wanted to feature the full body in most of the works, using the archways as a relationship to space. I also wanted to create new color relationships throughout each painting. For example, in Night Pockets — a previous series which focused on the lump-like figures — I was contrasting colorful figures with a solid background color. In Icons, I wanted the colors to contrast, weave, and transform throughout the entire canvas.

AS

Tell me more about the arches.

GR

The arches express confinement while referring back to religious painting. I found myself looking at a lot of medieval and renaissance art at the beginning of the pandemic. The use of archways and architecture as a framing technique stayed with me. So much of my work prior to this series has been about the internal frustrations of being confined to a body. In this series, I was able to show that claustrophobia within a space, how that frustration also arises externally.

AS

Tell me more about the frustration of being in a body. What does that mean to you?

GR

I feel like I am constantly parsing out my relationship to my own body, trying to understand the ways in which my psychological experience and my bodily experience coexist. Sometimes that coexistence is peaceful, other times it is hostile. I am always grappling with the idea that I move through the world in this vessel that can sometimes feel so familiar, and at other times so foreign. Ultimately, as a gender non-binary person, I find there to be many aspects of being in a body that can feel limiting. But at the same time it is a constantly evolving relationship.

AS

Has that relationship been impacted by the pandemic? These works feel so much like a direct response to the situation at hand.

GR

My work has always focused on the confinement of being in a body, and on the restrictions imposed by gender. This series builds upon these themes but takes them a step further, exploring what it means to hold all these feelings while being further constricted by a pandemic and unbreathable air.

AS

Going back to the arches, is religion something that is part of your world? Or are you interested in it as a visual language?

GR

I grew up in a reform Jewish household which included very little Hebrew school, studying for a Bat Mitzvah, and then synagogue on the high holidays. Our small congregation actually rented space in a church. While I don’t practice in quite the same way today, I definitely feel a strong spiritual and cultural connection to my Jewish heritage. Taking part in virtual services for the most recent high holidays was really important and impactful for me. I was able to watch the services of the congregation of my youth. This was a first for me and it was really nice.

AS

Where would you want these paintings to live, ultimately?

GR

Having started this series at the beginning of the pandemic, I made most of these works in a corner of my living room instead of in my studio. Even if I went to the studio one day, I would still bring the paintings home to continue working in the living room. As a consequence, I don’t think I have ever been so attached to a group of paintings — they were each a getaway for me. Each represents a place to which I could go or be. I hope they might do that for someone else.

Click here to view Rosenberg's exhibitions at Steve Turner

Please direct inquiries to:

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la