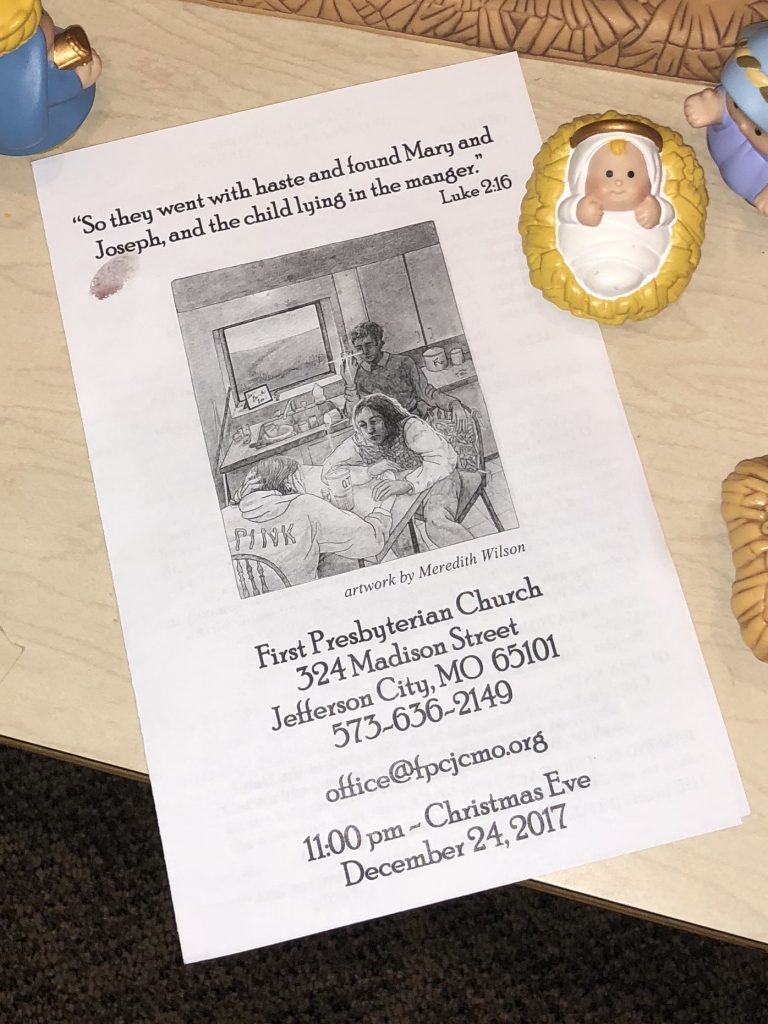

Meredith Pence Wilson (b.1992, Jefferson City) earned a BFA at Pratt Institute, New York (2014) and an MFA from Columbia University, New York (2020). She had a solo exhibition at Grease 3 Gallery, St. Louis (2018) and Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2020). Merdith has had work included in group exhibitions at Ki Smith Gallery, New York (2019) and Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2020).

Steve Turner:

I always am intrigued by artists who come to New York from elsewhere in the country and world and who bring their past with them and somehow meld the two. Can you begin by describing the place where you grew up, any early influences, and what you did before you moved to New York?

Meredith Pence Wilson:

I grew up in Jefferson City, Missouri, which is the capital of the state and geographically right in the middle. It’s not a big town, but it’s big enough to have lots of chain restaurants and two Wal-Marts, and an overcrowded public high school. I’ve always had trouble with the word “suburban” because it’s not anywhere near an urban metropolitan area, but it isn’t rural either. I grew up going to church two or three times a week, luckily one that generated more curiosity than resentment in my adult psyche. Other major influences were TV, family and nature. I often felt that my strength was observing, as I'm sure most kids do who feel they don’t quite fit in. Another product of this feeling was a need to prove myself -- to 17-year-olds who neither noticed nor cared. In retrospect, I think that is what motivated me to go to New York to study at Pratt.

ST:

What were your first impressions of New York when you moved there in 2010 at age 18? Describe your undergraduate experience. Did you remain in New York for a time or did you return to Missouri?

MPW:

New York inspired sheer terror. With each new person I met, I realized how unprepared I was compared to the other kids who were all better educated in art and life. I mostly remember how desperately I wanted to catch up. That led me to smoke cigarettes and pretend I knew what people were talking about, and it also motivated me to learn as much as I could. I studied illustration and worked hard at school, but the city provided most of the real education. After graduating I lived in Queens for a year and worked at a daycare, wrote a movie script with a friend, did some freelance illustration, and decided I wanted to move back to Missouri and paint. I left in the fall of 2015, and after a stint at my parents’ house moved to St. Louis.

ST:

What was the screenplay about?

MPW:

It was about a talented high school kid who graduates early and works at a parking garage. Then it turns into a kind of After Hours overnight adventure movie. My friend rewrote the script and shot it last year. Now it’s mostly about stand-up comedy.

ST:

I imagine living in St. Louis was a breeze after living in New York. What did you do there?

MPW:

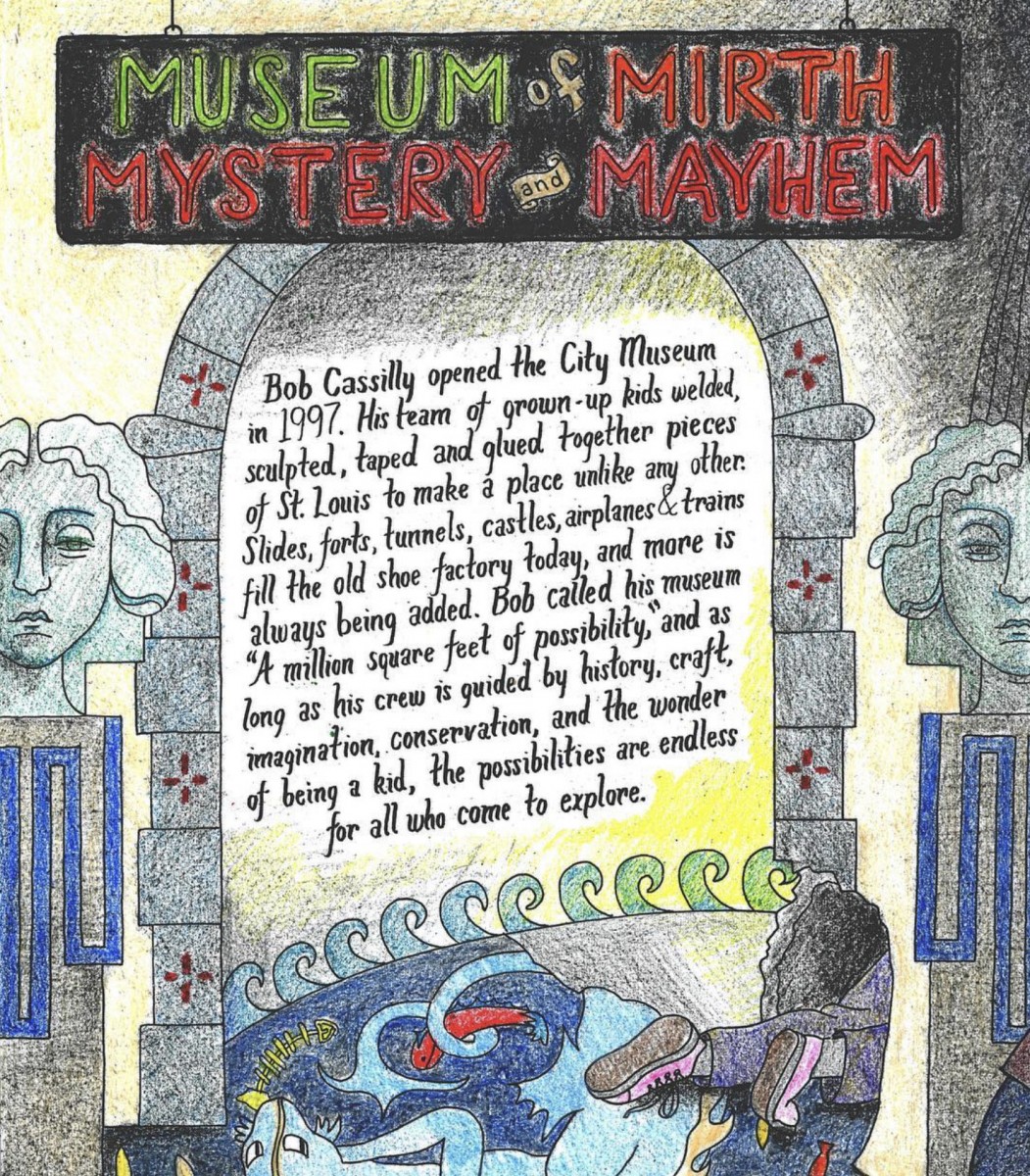

Yeah, it really was! I got a giant apartment and worked at the City Museum, which opened when I was five and has always been my favorite place in the world. As far as my influences go, it’s probably high on the list for early and lasting impact. It’s an interactive kids’ playground/museum/wonderland housed in an old warehouse in downtown St. Louis. I started out on floor staff, and eventually the director Rick Erwin let me do lots of projects -- a mural in a 10-story stairwell; a coloring book; signs and maps. It was more fun than any job I have ever had. I also had time to paint a lot. I shared a studio in an old brewery, and was lucky enough to have a solo show at a great artist-run space called Grease 3. I decided I wanted to apply to grad school somewhere along the way, and started working toward it in late 2017.

ST:

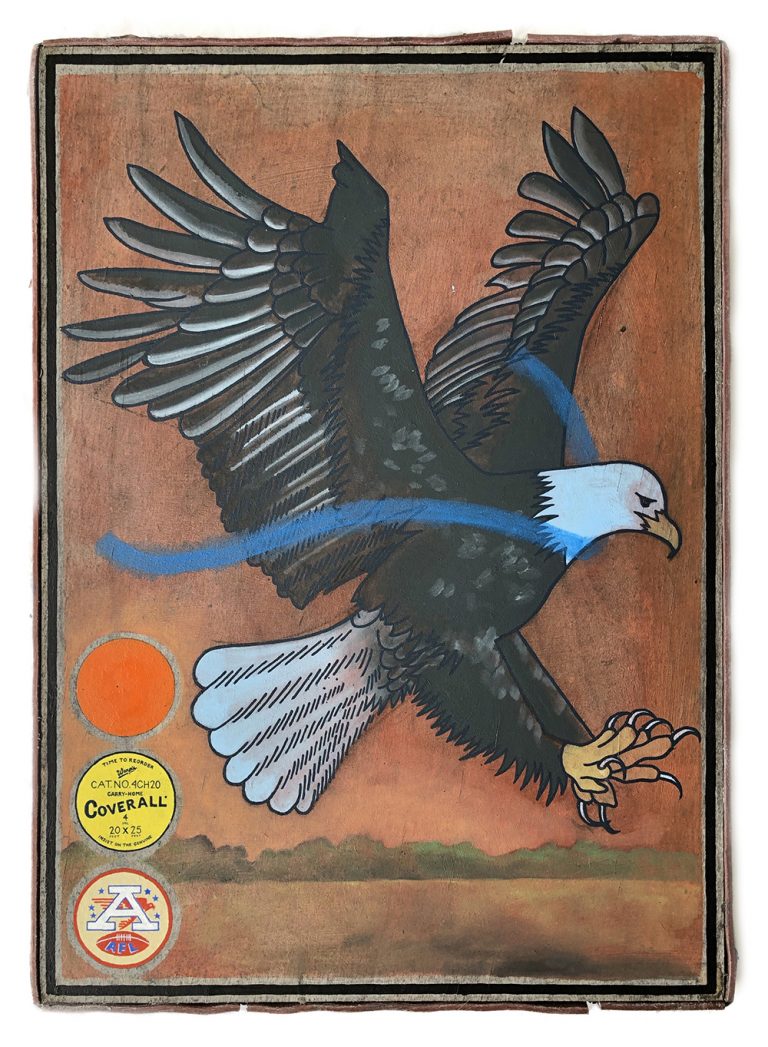

I can see how you were inspired by the City Museum. Some of your paintings of the last two years look like signs from a bygone era, the sort of historical object you might have seen there. Did it also give you a great sense of where you come from?

MPW:

Yes, and it’s still exciting every time I go. So much human energy collapsed in one space creates a dense feeling of history. The museum was really my first exposure to art, and it has continued to inform what I like–democratic curation; high mixed with low; funny and generous. The juxtapositions also collapse time–a piece of an ornate architectural cornice next to a neon sign, next to a mosaic, next to a window from an old farmhouse. The volume and delivery of information reminds me of an internet experience though I can’t think of a less digital place.

ST:

This leads us to your return to New York in 2018 for your enrollment in the MFA program at Columbia. Did you return to New York with more confidence that your experiences and observations also had a place in the art world? What did you gain from the two years at Columbia?

MPW:

I had some confidence that I could paint and draw, but I felt unqualified for the “art world.” I lacked an education in theory, so I was really seeking that, and got it at Columbia. I also took electives in the religion department which probably informed my newer work to an even greater extent. On the painting end of things, I made a real effort to break old habits and try everything–painting with oils, on canvas, on panel, loosening up, emptying out imagery, cramming it back in. Only this year, in the months leading up to my thesis show, did I feel like I was consolidating all I’d learned into a way of working that felt right. I feel that in these new works.

ST:

I see Missouri in your work. Is there now a bit of New York in it too? Or did going to New York free you up to focus on Middle America?

MPW:

I'm sure there’s some of my New York experience in the work, since I’ve lived there for so many years now. But I’ve always been more interested in the Midwest, visually and conceptually, probably because I feel like I can speak to it more directly. A painting I made last year called Red Scare was my attempt at making a picture about the lower east side: it shows two cheerleaders against a blue sky. So even when I aim to make work about New York, I use broadly American symbols.

ST:

Finally, can you provide a bit of insight into the five works in Roadmasters?

MPW:

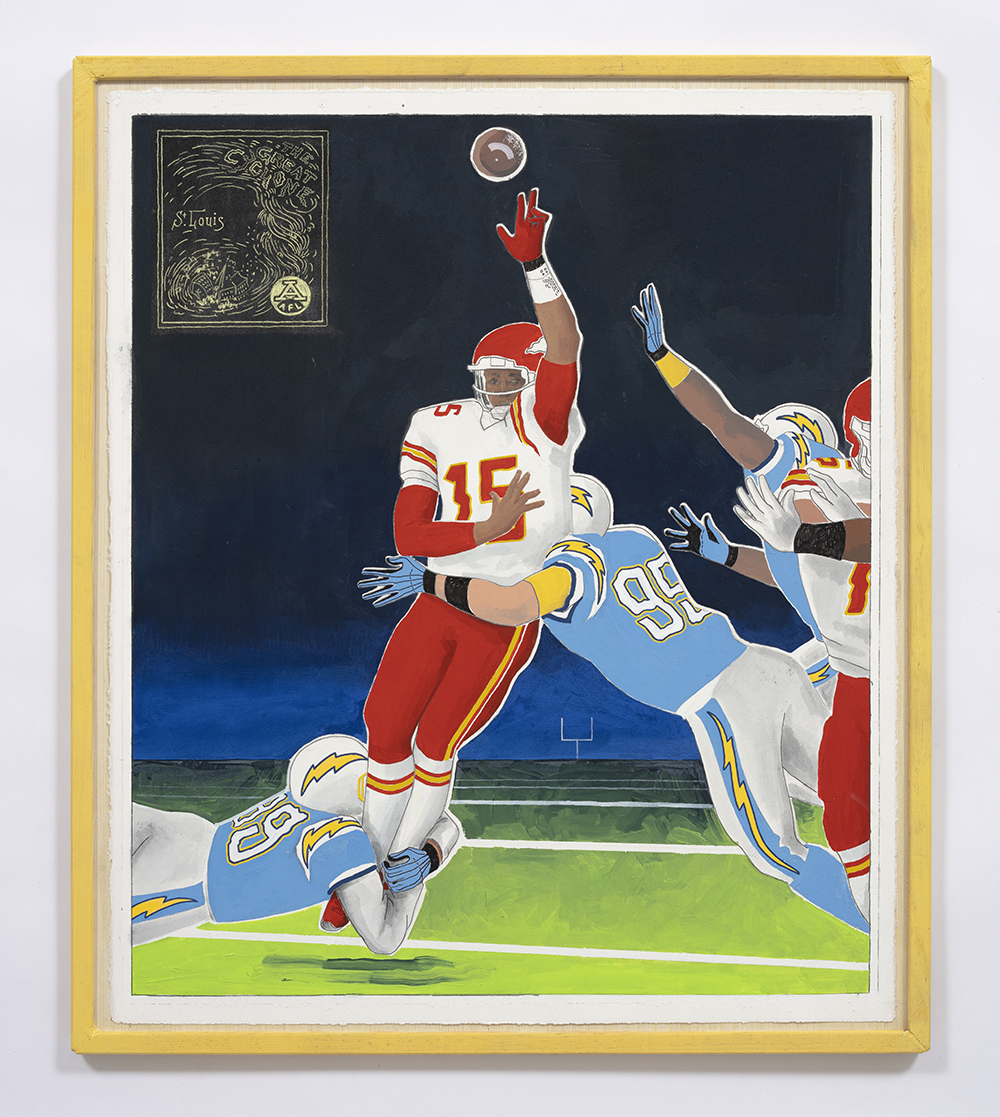

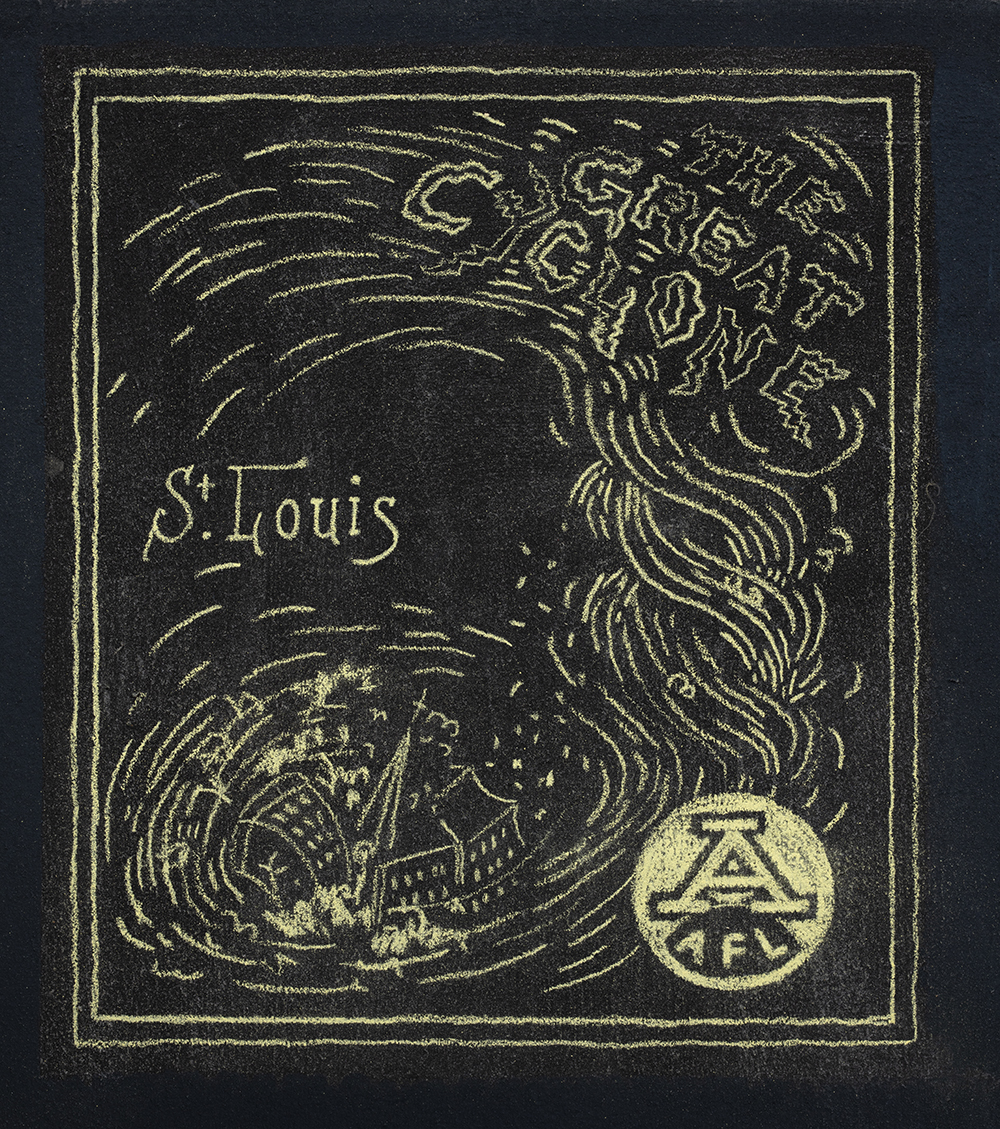

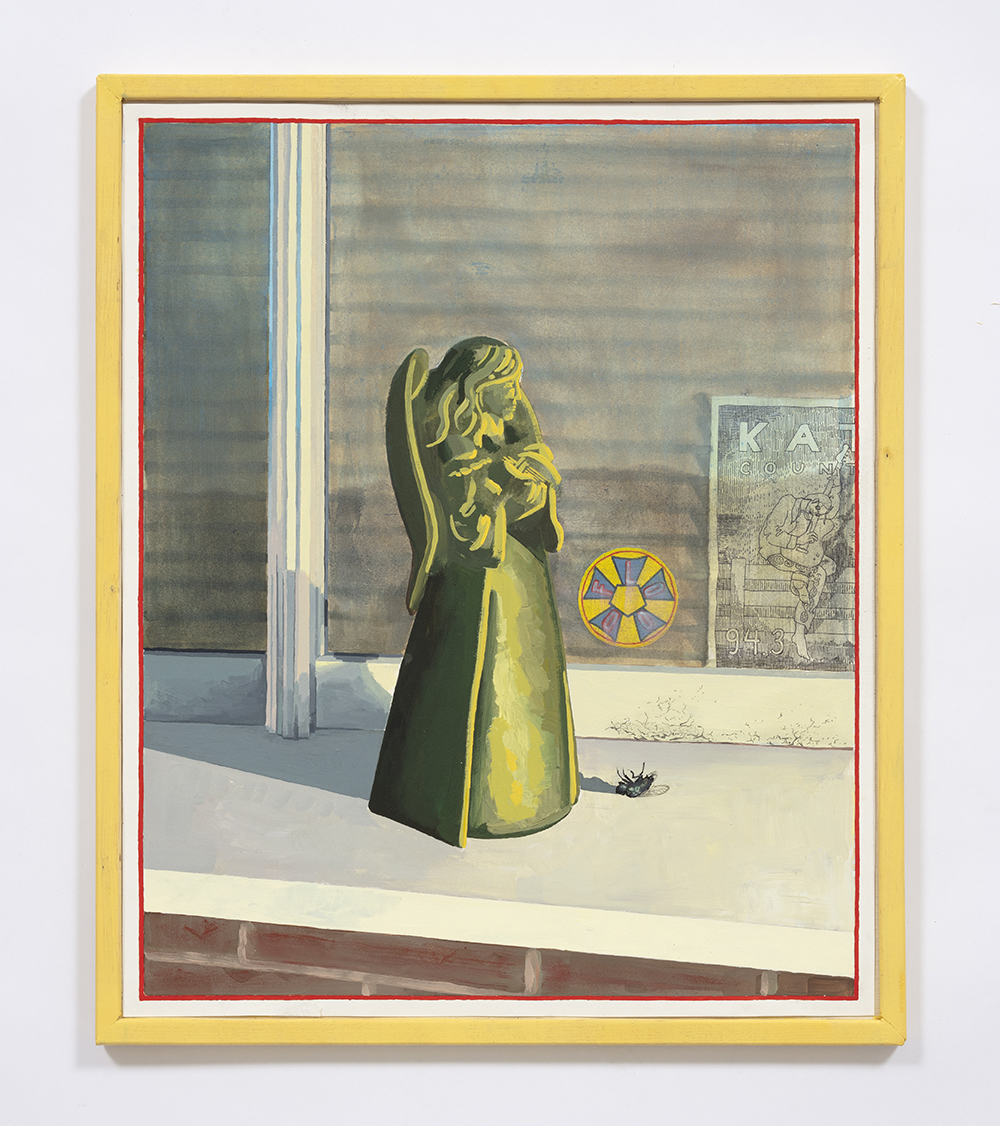

I’ve tried to present contradictions that point to the gulf between American mythology and reality. For example, an angel statue can be a kitschy souvenir. But it can also help someone who aims to be more devout express that desire. The football painting depicts a violent, money-making enterprise, one that simultaneously rewards practice and individual sacrifice for the good of the team. In pursuit of similar complexity on the formal side, I’ve incorporated diverse styles within individual works. There are passages reminiscent of sign painting next to impressionistic treatment. I find that engaging with these contradictions helps bring me closer to the truth.