Kate Klingbeil in conversation with Steve Turner

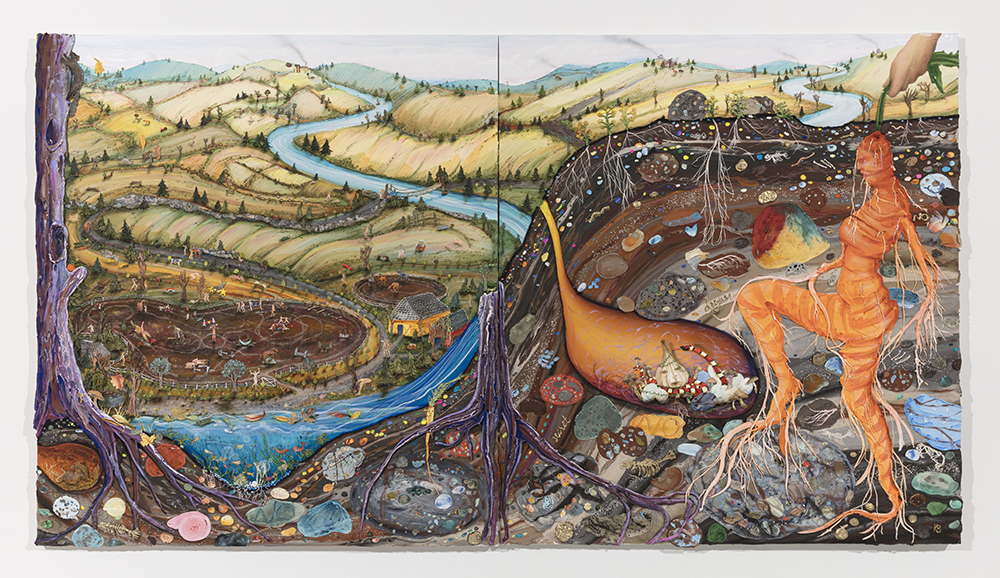

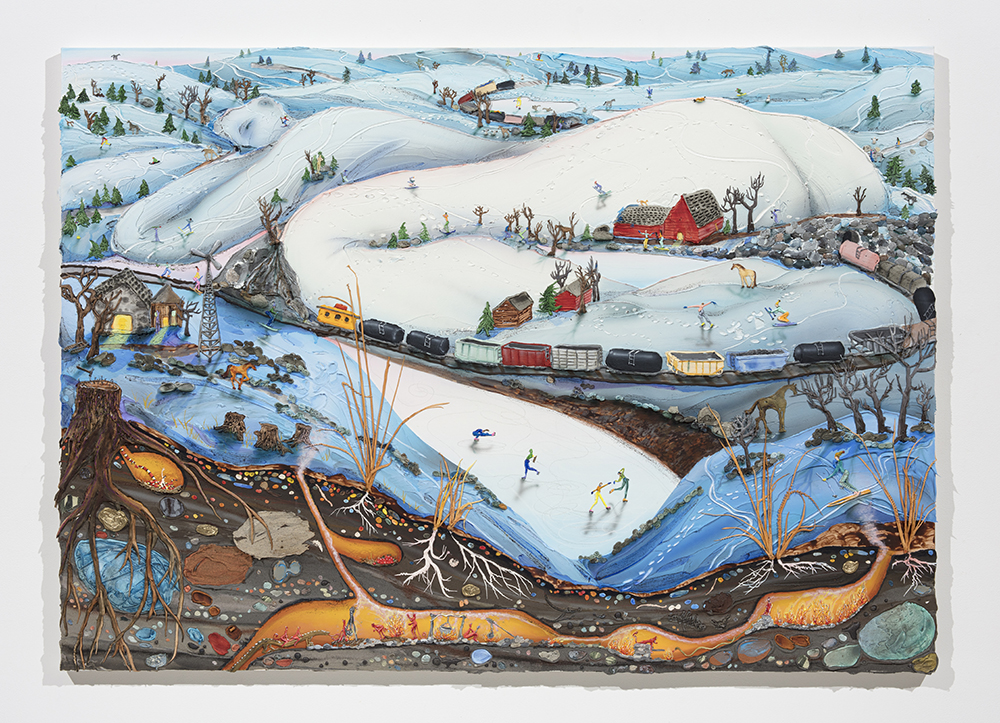

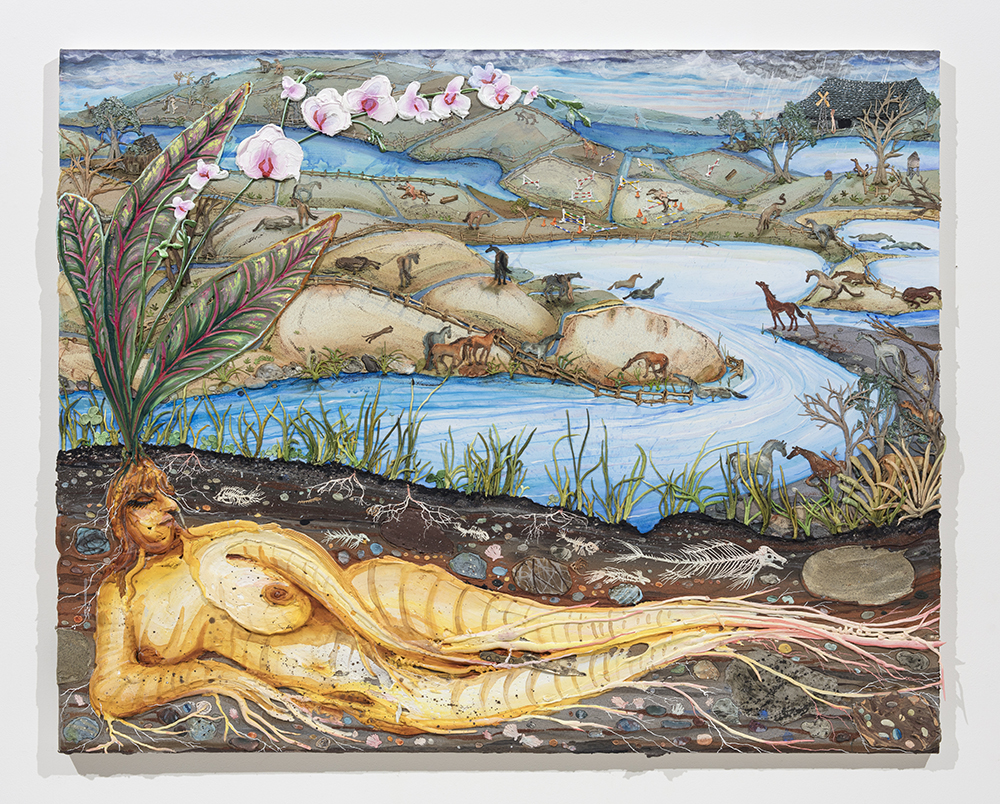

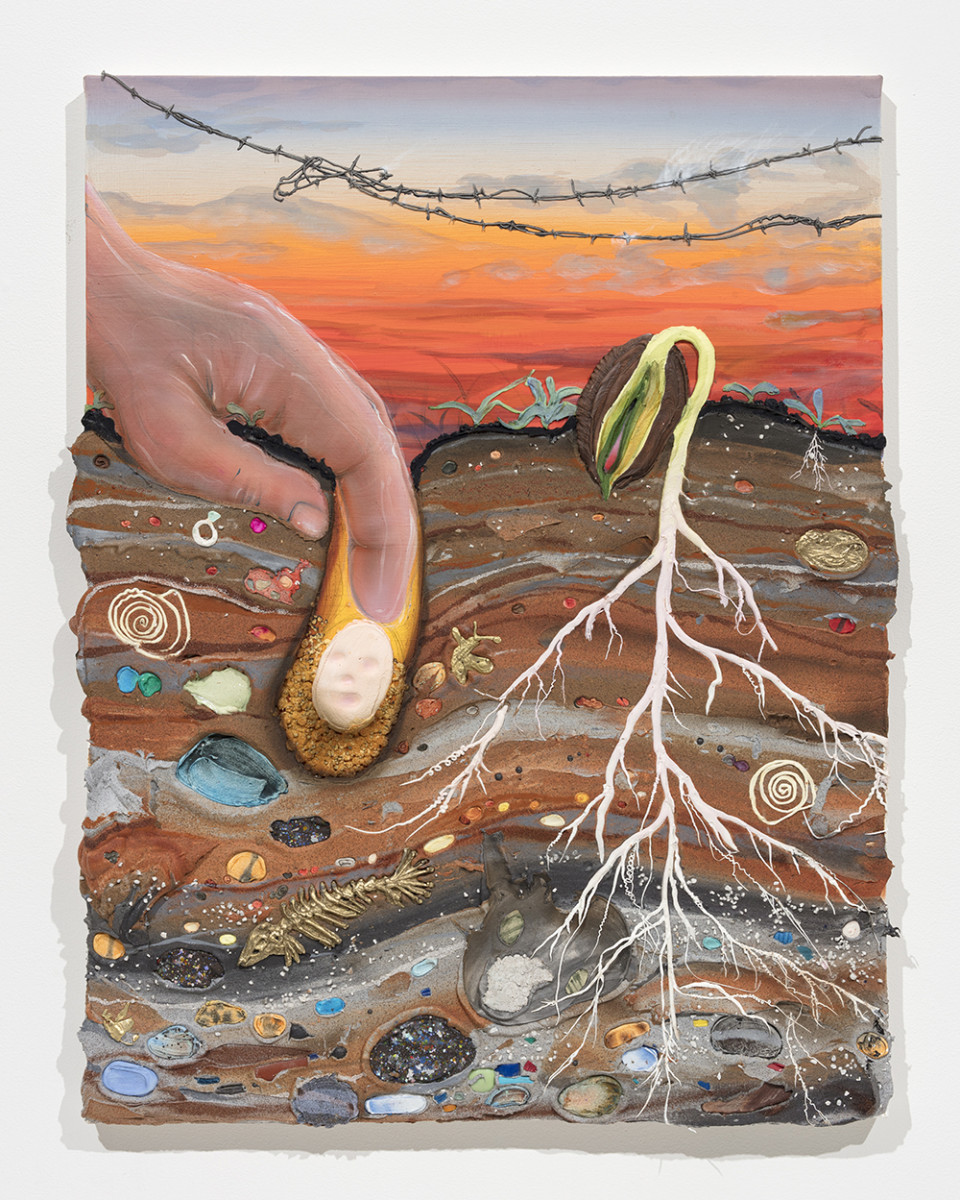

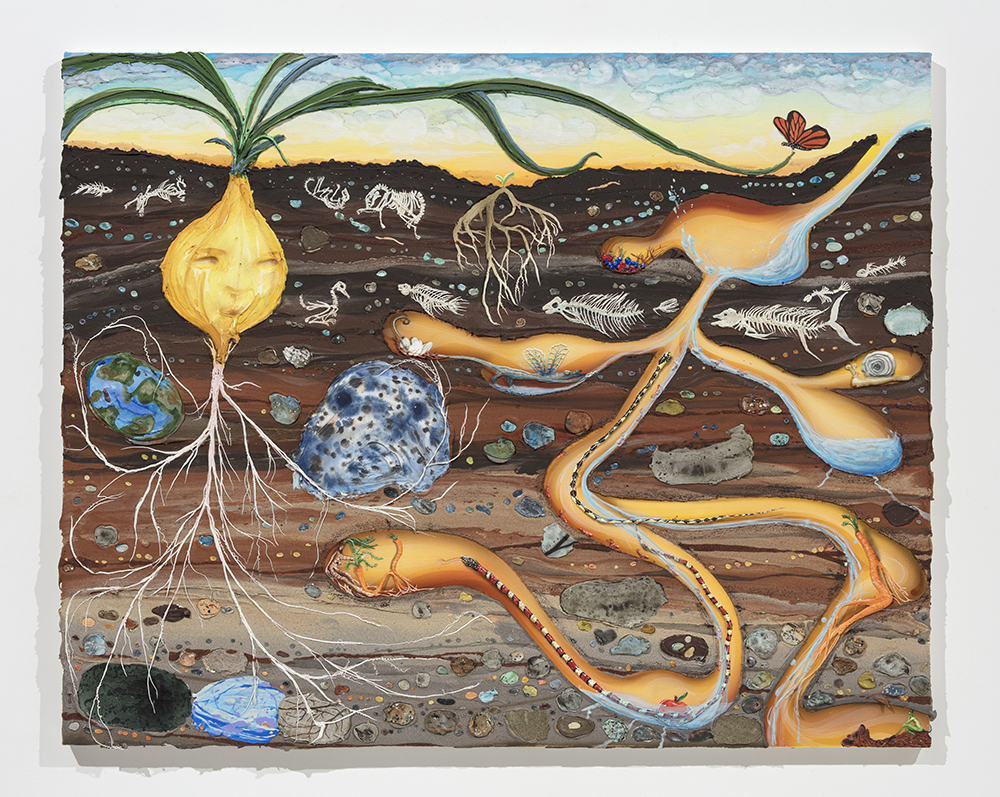

Kate Klingbeil creates highly textured, multi-layered paintings that depict scenes of nature, especially the small creatures that live underground, in pools of water and in plants and trees. It is the less visible nature of grubs, bugs, snails and ants, a nature that you have to look very closely to see, but a nature that Klingbeil has relished since childhood. It is a magical world in her paintings, a world that runs parallel to the complexities of the human body and its emotional system. Small details coalesce to form larger images. One might discern a human figure sleeping on the land when viewing certain Klingbeil paintings from afar, but up close, there are hundreds of little scenes working together.

Steve Turner:

I note that the works for Grown Woman were largely created upon your return to Wisconsin after the onset of Covid. Before we discuss your return, I would like to hear more about your early life. Where were you born? Where did you grow up? Can you describe the circumstances of your youth?

Kate Klingbeil:

I was born in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, about ten miles outside of Detroit. We lived there until I was five, moved to Kansas City, Kansas, then outside of Cleveland, Ohio, and eventually to Mequon, Wisconsin, which is about ten miles north of Milwaukee. I was twelve when we moved to Wisconsin and stayed there until I went away to college. I’m the oldest of three. I have two brothers who are two and six years younger, and we were always surrounded by animals. I used to have the neighborhood kids over to see all our pets. They’d be set up in the garage and I’d charge the kids a small entrance fee. I started riding horses when I was young and that became a huge part of my life until I went away to college.

KK:

My parents’ house in Wisconsin is next door to a stable, and on the edge of suburbia where it starts to become more rural. I would ride every day, and almost every weekend we’d pack up the horse to go school a cross country course or attend a competition. The sport I was involved in is called Eventing, which is basically the triathlon of horse sports. Part of a semester in high school was spent in Florida working for some Olympic level equestrians who taught me in exchange for mucking stalls. I really thought I’d go into riding professionally, but eventually I had to decide between horses and art as my focus, and I chose art. My parents house was decorated with detailed folk art, flattened maps, etchings, and watercolors by my grandparents, so that was the kind of artwork I was exposed to as a young girl. Though all of this sounds idyllic, and it mostly was, my childhood was also permeated with seriously dark moments, persistent health issues, and the facade of perfection that is common in suburban America.

ST:

We’ll return to this background when we discuss your work, but can you describe your California phase? After so many years in the midwest, you decided to go to college in California, at CCA in San Francisco. Were you looking for change? What did you gain from the experience and from living in San Francisco?

KK:

Yeah, California felt so different from where I grew up, and I wanted a big change. I loved that I could be outside year round and enjoy all these super varied landscapes. You can look out on the water, hike in grassy, rolling hills or feel small in a redwood grove all in one day. I studied printmaking at CCA, which at the time had a pretty traditionally focused program. It was at CCA that I learned about bay area figurative painters like Richard Diebenkorn, Nathan Oliveira and Joan Brown who all had a big influence on my work. CCA was where I fell in love with stone lithography, monotypes and etchings, and after school I worked as a contract printer for a second.

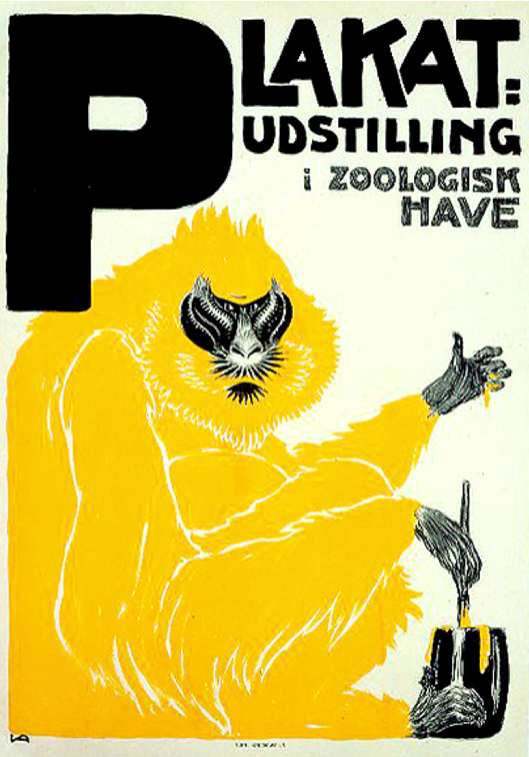

After I graduated in 2012, I ran a project space called Turpentine out of a live/work storefront next door to the deli I worked at. Turpentine was this space where we could get weird and put on shows and themed parties. While I ran that space, I also worked at this vintage poster gallery in Berkeley. I sold and restored original posters from the 1890’s-2000’s and we traveled around the west coast to trade shows. I’d stand behind a table and flip the posters from one pile to another. I’d talk about each one and try to read people’s body language to know which ones to quickly pull from the pile for a second look. I learned about the history of advertising, and lightweight conservation at that job, plus I had the printmaking background to know how they were made. That imagery definitely impacted my paintings. I was in Oakland for eight and a half years. I left for New York in 2016, but I’ll always have a soft spot for the Bay Area.

ST:

The opportunity to discuss rare posters for a minute is too exciting. Did you know that I have been collecting and dealing in rare posters since the mid-1980s? I wonder which specific posters impacted your paintings. Can you share a favorite? I’ll share one too.

KK:

I did know that! My poster was printed in 1895 in Wissembourg on the border of France and Germany and was made to be a carnival decoration. This one shows a frog playing guitar, but there’s a whole series with different characters. I got it in 2016 and it was one of the oldest posters at the gallery I worked for. I thought about it for like three years before I finally went for it.

ST:

Armed with your knowledge of various printmaking processes, you struck out for New York. Did you have a plan? Did you develop the painting practice that you now have once you got to New York?

KK:

I think I just needed another big life change, but I didn’t have a super focused plan. New York made the most sense to me. In New York, everything felt both difficult and rewarding. The city can hand you something magic when you think nothing is going right. That was really intoxicating. I started making thick paintings in Oakland, but further honed my process while I was in New York. I didn’t start this collaged paint method I use now until sometime in 2018. Previously, the paintings were made using a totally direct method of application. Maybe the way I was making stop motion animations at that time ended up informing the painting technique I use now. Something clicked for me when I realized I could give myself the freedom of making the painting in parts.

ST:

Let’s talk about the paintings in Grown Woman. They have numerous layers, including little details that you paint on a piece of plastic and then attach to the painting. Can you describe this process and the way you build up your paintings?

KK:

The paintings start with a tiny plan in my sketchbook that I translate to the canvas with paint or pencil. Usually they start on the ground, with a pool of watery acrylic that dries over a few days. I build my surface from a thick medium mixed with pigment and acrylic. Many of the details are made separately from the canvas by piping paint from pastry bags onto plastic sheeting. Once those dry, I’ll paint them, peel them, and then pin them to the painting using quilting pins. When I know they’re in the right place, I glue them, remove the pins, and continue to paint on them to integrate them further into the scene. It’s essentially a collage process with paint and sand.

There’s another method I use, which you’ll see in the underground sections and the snow. For those, I’m spreading out fields of paint with palette knives and pushing the dry pieces into the wet paint. I’ll organize the small parts I might use on the floor, grouped loosely by color and category, and then I’ll pick and choose which ones go in the painting in the moment. There’s a short window of time, like an hour or two if I’m lucky, before the wet paint gets a skin and won’t accept the bits I’m inlaying- like a race against the clock, or a game I’m playing with the painting. All of the root people in these are made specifically for each painting, but I also have collections of rocks, bugs, people and trees that I pull from...parts from years past that didn’t make it into the previous body of work. The paintings for Grown Woman also contain cast brass and iron, a new addition to my work.

ST:

I think it is interesting that you started working with metal for Grown Woman. How did this come about? Are you excavating deeper into the earth?

KK:

Yeah I’m really excited about this new medium and combining paint and castings. I just finished a three month residency in Wisconsin where I made the new metal work. The residency is called the Arts/Industry Program at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, and it’s actually inside the original Kohler factory, where they produce functional Kohler products like cast iron sinks, bathtubs, toilets and engine parts. It’s very much a working factory, with all the loud noises, soot, forklifts and raging fires. Artists can apply, and then are invited to work in the factory, using the same processes and materials that Kohler uses in their manufacturing. The new works are all made out of cast iron and brass. It was incredibly consuming and physically demanding, and one of the most rewarding experiences of my life, plus It felt really right to come back to Wisconsin for this residency, just 45 minutes north of where I grew up.

I had about a year to think about the work I wanted to make at Kohler, so the concepts evolved alongside the paintings for Grown Woman. Coming back to this landscape was healing, and then making these heavy, strong, enduring pieces from metal, a material that is so closely linked to the earth’s core, solidified everything I’ve been thinking about in my work over the last few years.

ST:

What an amazing residency! And what an amazing coincidence that it is situated in Wisconsin, the state where you mostly grew up. I want to understand better your philosophy of landscape, how you came to love the texture, mystery and significance of the landscape that is below the surface of the earth. Did you dig for things as a child? In your paintings, there are bare hands, feet and bodies entering and lying on the earth. Is that you?

KK:

As a child I was always searching for this miraculous, elusive world of insects and animals that I knew was there, just out of sight. I was obsessed with finding small creatures, and that included digging in the dirt. I have this distinct memory of digging for grubs on the playground in grade school. I’d search for these little translucent white larvae with their bright red heads like it was my job.

The bare hands and feet in the paintings could be mine; they could be anyone’s, but they’re really meant to act as a bridge between reality and fantasy. I want to enable viewers to see the place that I found for myself when I was a kid. I knew there was a secret, magical world that would reveal itself if I stood still enough and waited. I also want viewers to see the impact of human intervention upon and within the earth. The human hands and feet are mischievous disruptors. They are meddling with nature in their desire to control the natural world. I wish they would simply admire the magical power below.