August 22–September 19, 2020

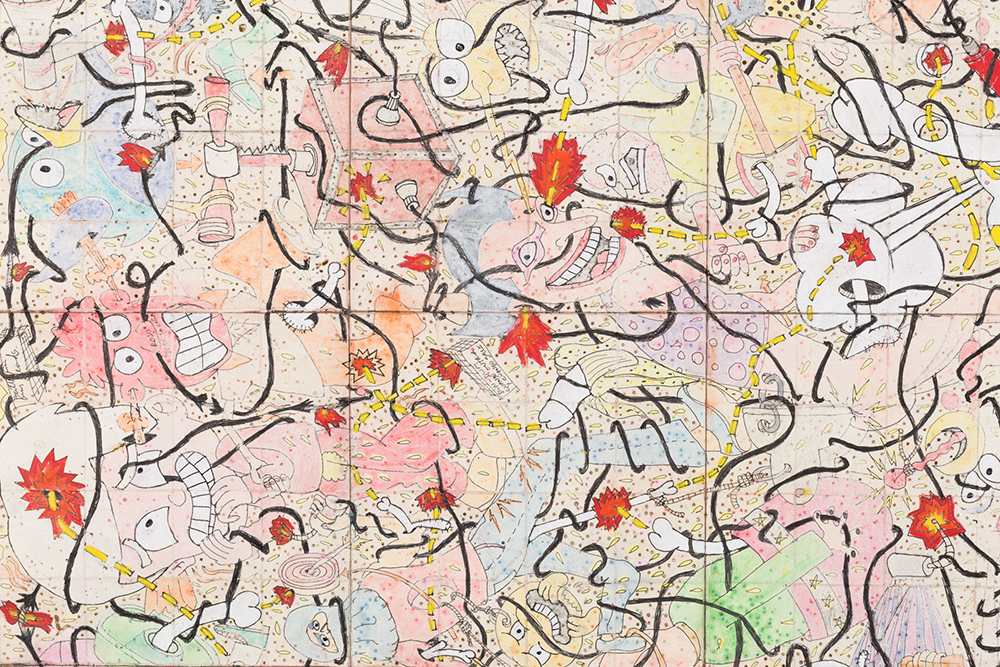

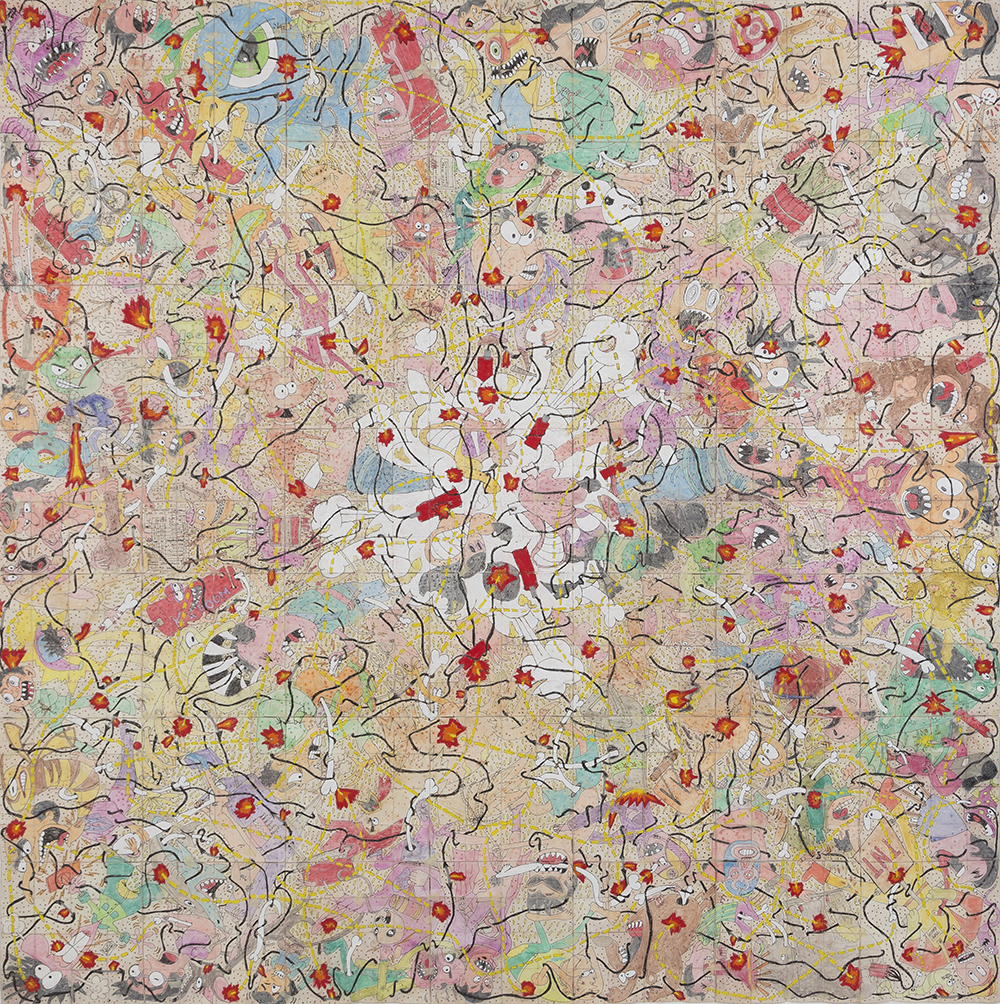

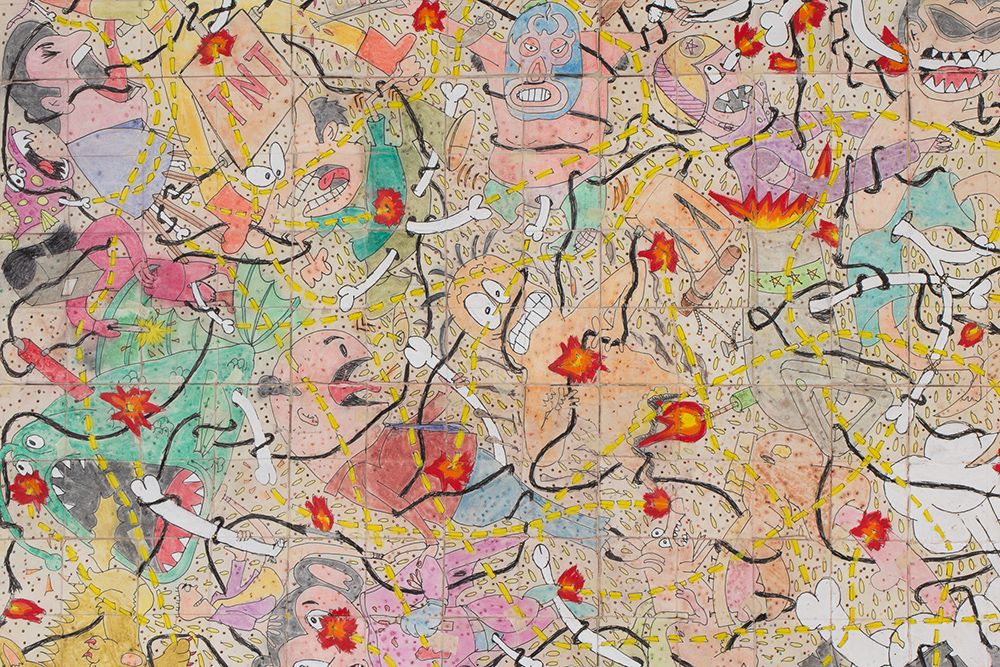

Steve Turner is pleased to present Pescando Con Dinamita, a solo online exhibition by Medellín-based Camilo Restrepo that introduces two new series of work–Pescando Con Dinamita and Juegos Finitos / Juegos Infinitos. In the former, Restrepo continues his practice of creating large scale drawings that bear numerous scars. When he completes the drawing phase, he perforates the paper with a soldering iron before causing all the colors to run by spraying water at high pressure. He then meticulously repairs all the damage. The title refers to the brutal practice of fishing with high explosives, something that is done in Colombia. Restrepo sees this as another aspect of our hyper-masculine culture, one that mostly relies on violence to solve its problems.

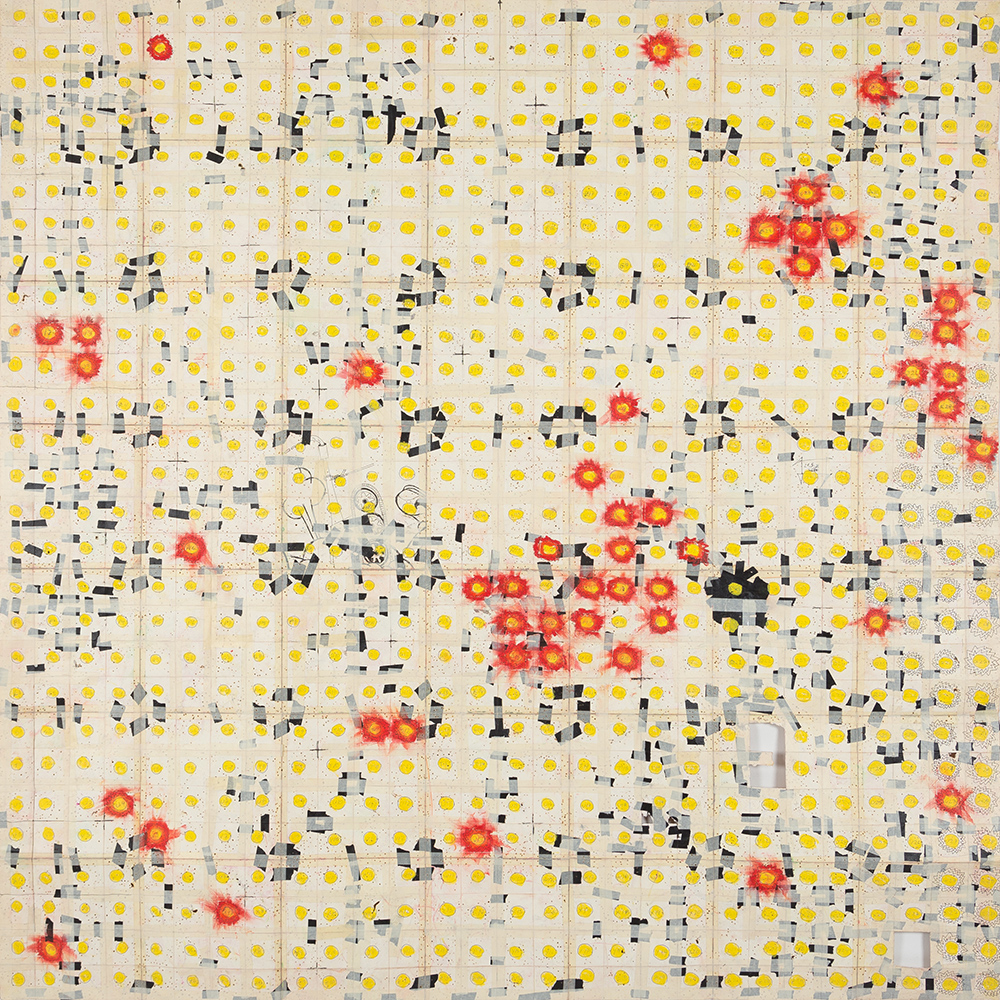

In the latter series, the artist first downloaded a photograph from the Internet of someone who was killed in connection with drug trafficking. He then digitally erased the background and printed it in the 1 x 1 inch format of a passport photograph. He then aggressively drew upon the image in red ink, re-photographed it with a macro lens and finally, printed out the image in a larger size. These steps rendered the subjects largely unrecognizable, as though their faces were obliterated by violence. In so doing, Restrepo aims to draw attention to the Colombian practice of glorifying death while pointing out that the war on drugs has caused deaths on all sides of the issue. Good people are killed by narcos and narcos are killed by the police and each other. In this series, every mutilated face is nearly the same.

Camilo Restrepo (born 1973, Medellín, Colombia), earned an MFA from CalArts (2013) and a masters degree in aesthetics from the National University of Colombia (2008). He has had solo or two-person exhibitions at Sala de Arte Suramericana, Medellín (2019); Steve Turner, Los Angeles (2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019) and the Lux Art Institute, San Diego (2016). Restrepo was a recipient of the Fulbright Grant and was nominated for the Premio Luis Caballero, the most important prize in Colombia for artists over 35. A major monograph, Alias, was published in 2019. This is Restrepo’s sixth solo exhibition with Steve Turner.

Camilo Restrepo in conversation with

Aino Frilander, Helsinki-based critic & curator.

Aino Frilander:

You’re based in Medellín, Colombia, and you told me that you don’t really have an artistic community there. What is it like for you to work there as a lonely wolf, so to speak? I think you had more of a community around you when you studied at Calarts.

Camilo Restrepo:

It is paradoxical because I went to Calarts in search of an artistic community where I could talk and debate about art. The time I spent there was so transforming that when I came back to Colombia, I was more into drawing in total solitude. I sit every day to draw, with my thoughts, anxieties and obsessions, and the process is so immersive that oftentimes I feel I’m the creation of my drawings instead of the other way around.

AF:

What do your days look like? Has Covid-19 changed them?

CR:

I wake up early and meditate for an hour, then I sit down to work. Normally I work for about 10 hours with a rest in between to have lunch, but it can go up to 16 hours if there is a deadline to hit. I don’t believe in art inspiration, I believe in art discipline.

As I am used to working alone, the confinement due to Covid-19 didn’t change my schedule. At this point we have been under quarantine for 149 days in Colombia. What changed however, was the subject matter, as my levels of anxiety were so high. During the first months of the lockdown I made a lot of drawings about the coronavirus. After things got more normal in my head, I was able to start making the drawings for this show.

AF:

Are you thinking of ever showing the coronavirus drawings? What were they like?

CR:

I filled an entire sketchbook with green drawings related to the coronavirus molecule. If I were to show them I would have to create a more elaborated series based on the sketches, or show the sketchbook itself. There were a couple of different themes. I made a drawing called The Great Curve off Wuhan that I will draw in large scale, which obviously refers to Hokusai’s woodblock print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Never before has the word ”curve” been used more than now. There also is a series of portraits based on cartoon characters with antennae, as if they were the visible face of the virus, such as Shrek, Bender, Rosey The Robot, the Teletubbies and so on. I also worked on a character that I created at Calarts, my alter-ego, as if he was an entity captured by Covid-19.

AF:

You’re showing two bodies of work with Steve Turner, Pescando con Dinamita and Juegos Finito / Juegos Infinitos. Both are quite violent in their own way. Can you talk about the role violence has in your work?

CR:

The role of violence is always in my work. Imagine a city in which going out can be a death sentence. That was the Medellín in which I grew up. There was a war between the narcos and the government, and the problem continued with the War on Drugs. This insane war has killed thousands and thousands in Colombia. Somebody once said that every gram of cocaine that is sniffed in Europe or in the United States comes with a stream of blood.

AF:

In Pescando, you deal with blast fishing, which is kind of an insane practice when you think about it - stunning and killing all fish within range and destroying the underwater ecosystem with a single explosion. Do you fish yourself? And is blast fishing a common practice in Colombia?

CR:

All my life, I have gone on holidays to an island in the Atlantic Ocean off Colombia called Isla Fuerte. I learned to fish there in an unsophisticated artisanal way. That’s also where I saw people fishing with dynamite for the first time when I was a little kid. The fish appeared dead, floating on the surface.

The guy who took us from the mainland to the island in his wooden boat had lost his right arm. It was blown off when he was fishing with dynamite. It made me realize how violence could be a boomerang that returned recharged.

AF:

Blast fishing is of course also a symbol of excessive use of power. I’m guessing it’s also related to the bones and boners in the work. What does that use/abuse of power mean for you? Is it a male thing??

CR:

It means disrespecting the life of others, from small injustices to assassination. Even though abuse of power is not performed by men only, it mostly happens in hyper-masculine cultures where to be a man (to be important, powerful, relevant, successful) is to participate in these dick measuring and pissing contests.

AF:

And Colombia is like that?

CR:

Colombia mostly is a sexist, religious country. Women and minority groups are often discriminated against, more so when there is a right-wing government like the one now in power. This, combined with the narco attitude of “eliminating everything that’s in the way”, the high levels of corruption, the abuse of justice by legal and illegal forces, as well as poverty, does create a breeding ground for power abuse.

AF:

You like to destroy your work in many ways – blasting it with water and poking at it with soldering irons. Why is that?

CR:

On a physical level, I use different kinds of destruction methods in order to produce specific visual results. Those methods are very difficult to control, so they allow the unexpected to happen. The destructive methods also emphasize the materiality of the paper, which acquires sculptural characteristics. On a metaphorical level, as the drawings are so complex and take so much time to be finished, these methods also allude to how easy it is to overuse force to devastate what has been carefully accomplished and how painful it is to rebuild what has been lost.

AF:

Why is loss or perhaps loss of control important for you?

CR:

On the one hand, mental suffering is linked to the idea that we are in control. Acknowledging randomness helps lessen the burden of thinking that there is a ”self” that steers the spaceship. Things arise and disappear and the self is just an appearance in consciousness, as is any other thought or feeling. On the other hand, when a loss is caused by power abuse it is important for an artist to make it visible, to take a position and to contribute to a debate about it.

AF:

The level of detail is your work is stunning, and conveys a feeling of certain obsessiveness or maybe exorcising your own demons. Can you talk about that?

CR:

There is an apt saying in Colombia: ”La cabeza es la loca de la casa” meaning the head is the crazy of the house. So yes, the process of drawing serves as a catharsis, as a way for me to befriend my demons. Regarding obsessiveness, it is strange how filling the blank space has a snowball effect–the more I draw, the more difficult it is to leave white space. Since Google is my source of images, there won’t ever be enough space to accommodate everything. This resembles how I feel with my repetitive thoughts.

AF:

What are your repetitive thoughts like? Have you always had them?

CR:

I underwent psychoanalysis for 15 years – which I ended disliking because of the power differential between the doctor and the patient. I also take psychotropic drugs. Rivotril is my best friend, seriously! I have suffered in my head as long as I can remember. The thoughts are mostly about being ashamed of oneself and about being insecure of expressing my opinion because people are going to realize I am a fraud. They are about the fear of appearing weak, of making mistakes that will make people run away from me. Nevertheless, I have worked a lot to understand how my mind works, to unmask the ego, to exorcise my demons. But they are smart: they don’t go away, they wait for the perfect moment, crouched in a corner of the mind, to say hello again.

AF:

I guess they never do disappear completely! But for many of us, art is a way of dealing with them. Do you have any favorite artists who work with obsession?

CR:

The artworks I enjoy the most are the drawings made by outsider artists. A turbulent mind that expresses itself is very moving to me. I also strongly identify with so called outsider artists as I have no formal training in drawing and I likewise have a turbulent head.

AF:

Who are the outsider artists whose work you enjoy?

CR:

Sister Gertrude Morgan, George Widener, Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, Sam Doyle, among others.

AF:

Your other series, Juegos Finitos / Juegos Infinitos, takes reproduced and destroyed photos of dead people as its starting point. Who are they and why did you choose to include them?

CR:

All are people who were assassinated. It’s a horror gallery of corpses that the narcos and the War on Drugs have left behind. They are politicians, journalists, paramilitary and guerrilla group members, narcos, soccer players and referees, human rights defenders, hit men and more.

The first portrait in the series is of Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, the Minister of Justice who was killed by Pablo Escobar in 1984. That murder started the war between the Cartel of Medellín and the establishment. Another is of Andrés Escobar, a Colombian national soccer team player who was killed because he kicked a goal into the wrong net during the World Cup in 1994. There also is one of Pinina, a sicario (hit man) who worked for Pablo Escobar. But it is not his real face. Instead it is a photo of an actor who played him in a TV show called El Patrón Del Mal. It is very interesting to me how the narratives about narcos are constructed and how fiction and reality intersect in them.

AF:

You started the series with a photo of Pablo Escobar, and you explained to me that you scribbled at the photo in fury, destroying it in the process. What sort of a presence has he been in your life?

CR:

He is the very symbol of power and excess. He is the person that brought an entire country to its knees. He is the poster child of devastation, the guy who bent through “plata y plomo” the history of Colombia.

AF:

A lot of your work deals with the effect drugs have had on Colombia. Do you ever feel locked in by that theme?

CR:

Not at all. The illegality of drugs and, consequently, the War On Drugs, still have a tremendous impact in Colombia. It is not an issue of the past. There are thousands of people killed, displaced and recruited by illegal groups every year because of the way we deal with drugs and the amount of money the illegal business generates. It is happening right now. That is why I constantly revisit that theme. It’s a moral obligation.

Click here to read an earlier interview with Restrepo

Please direct inquiries to

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la