Claire Whitehurst: Mississippi Shade

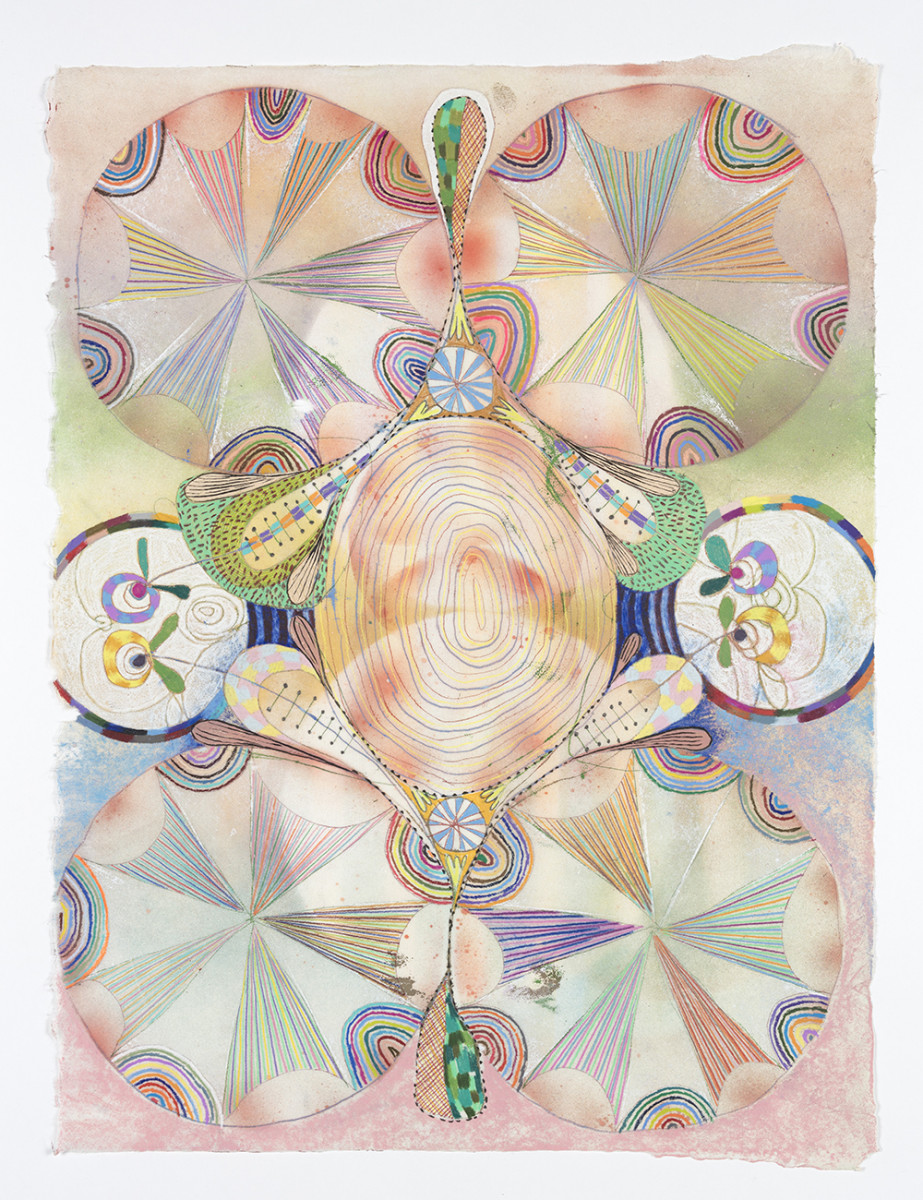

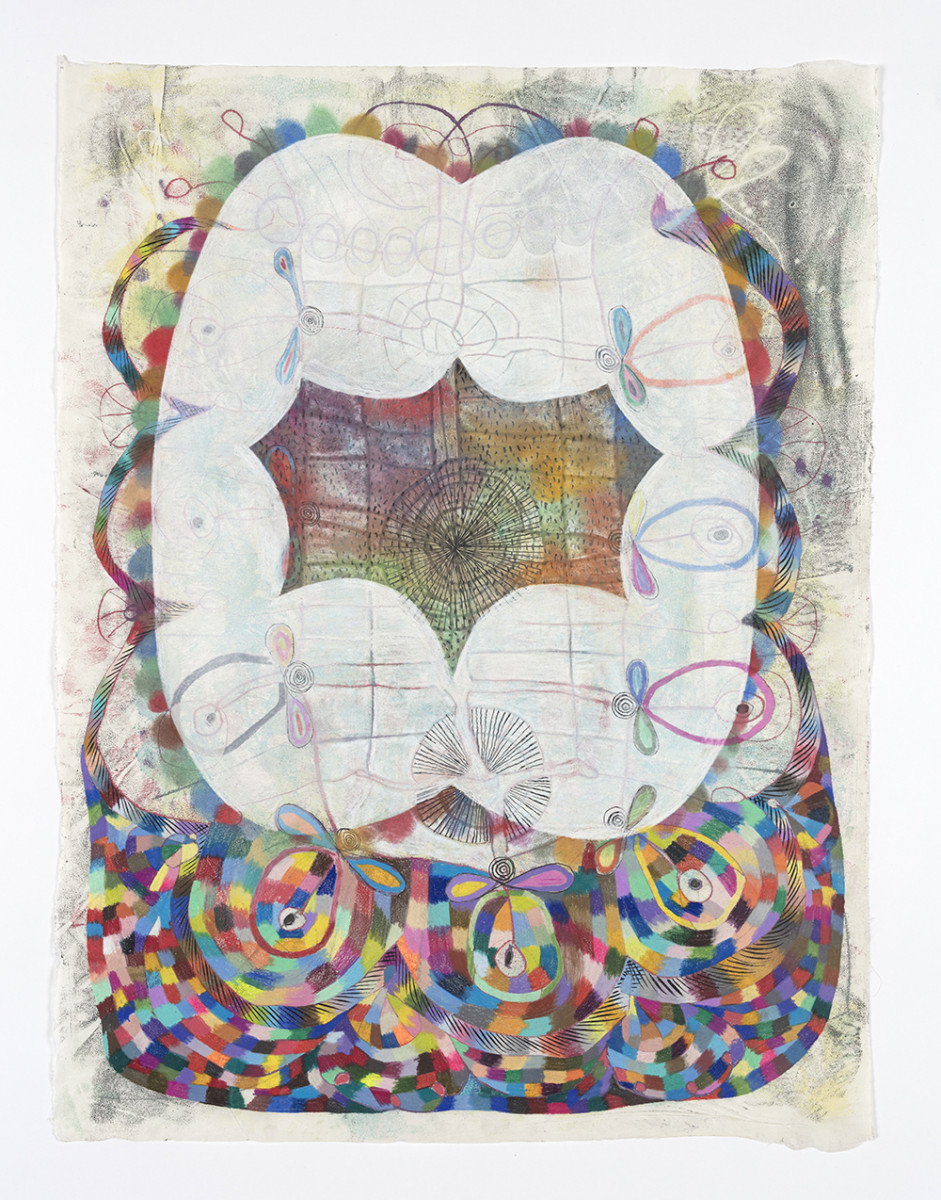

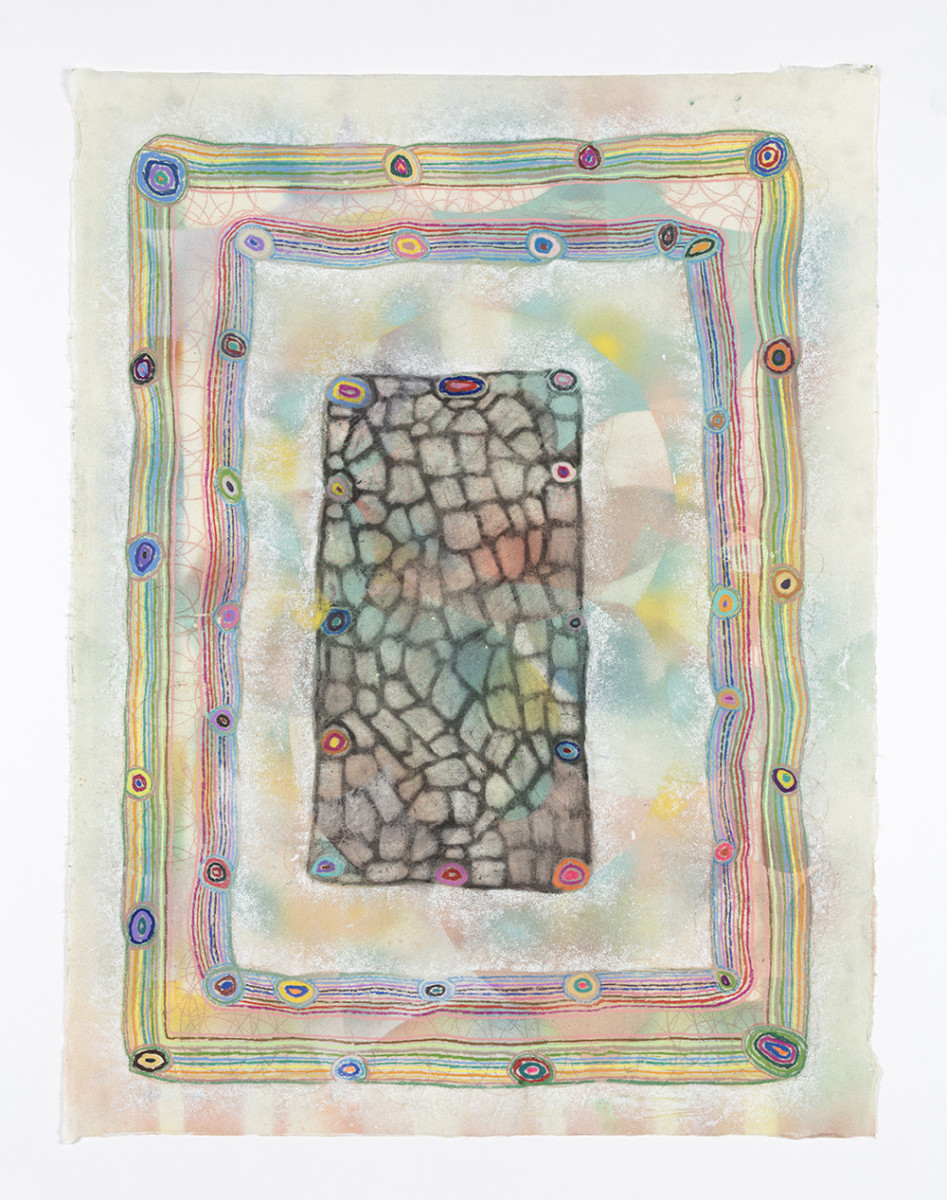

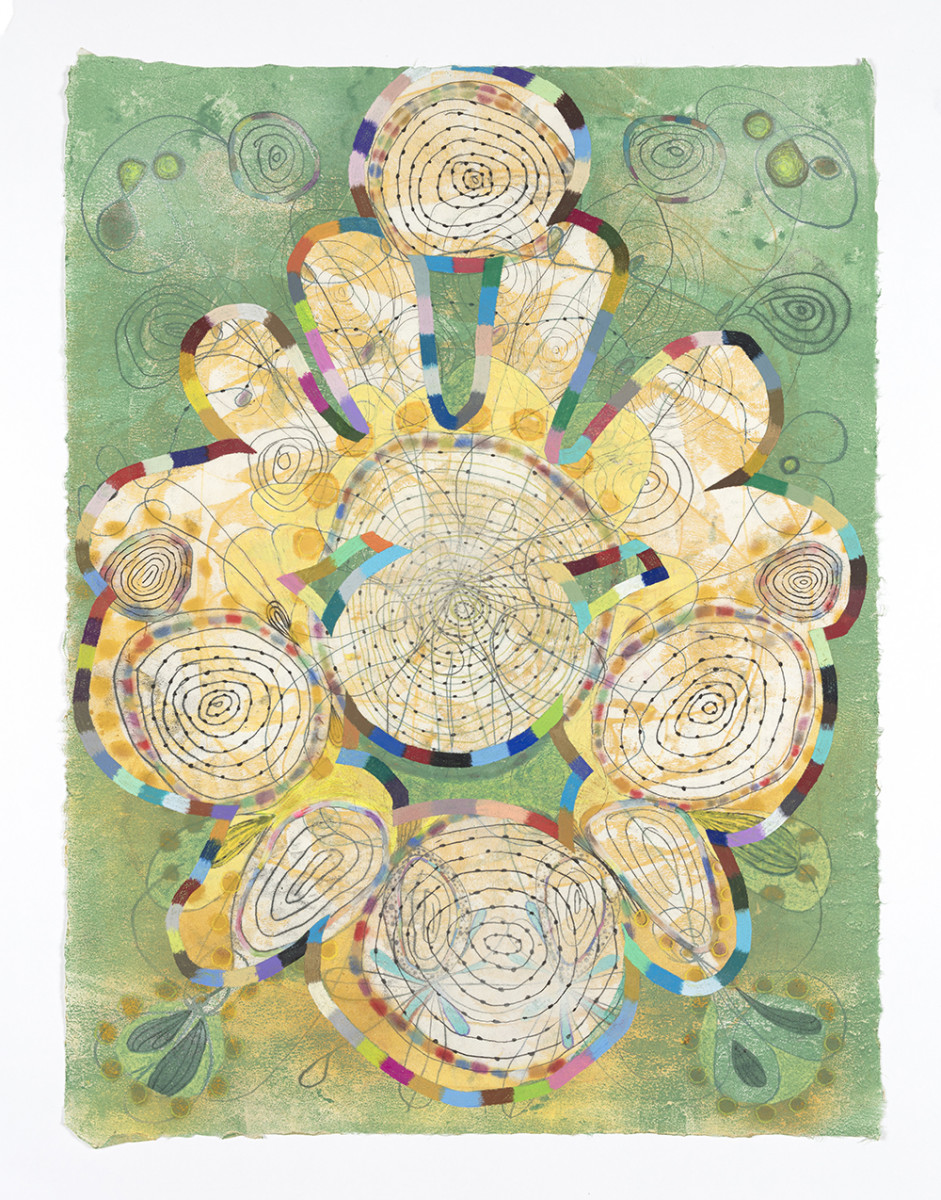

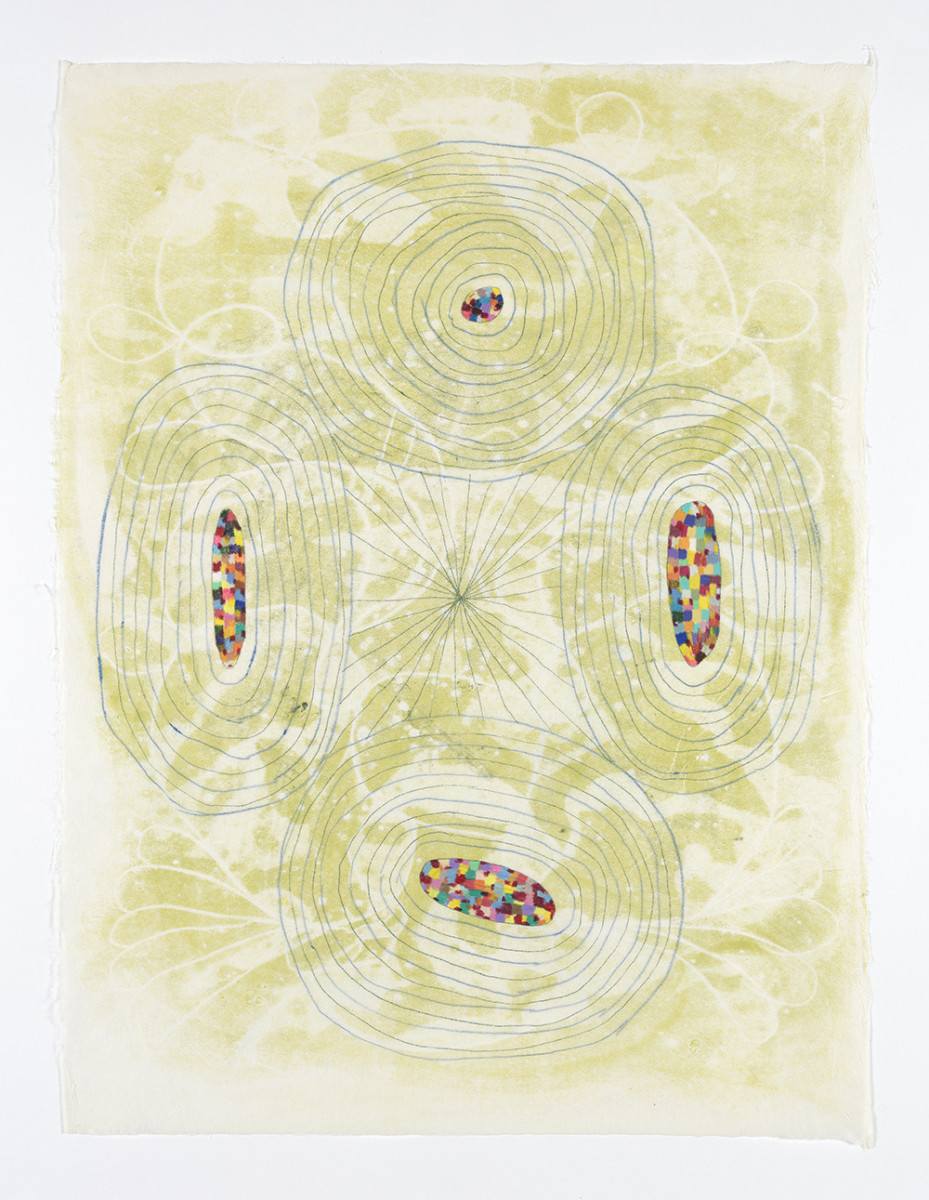

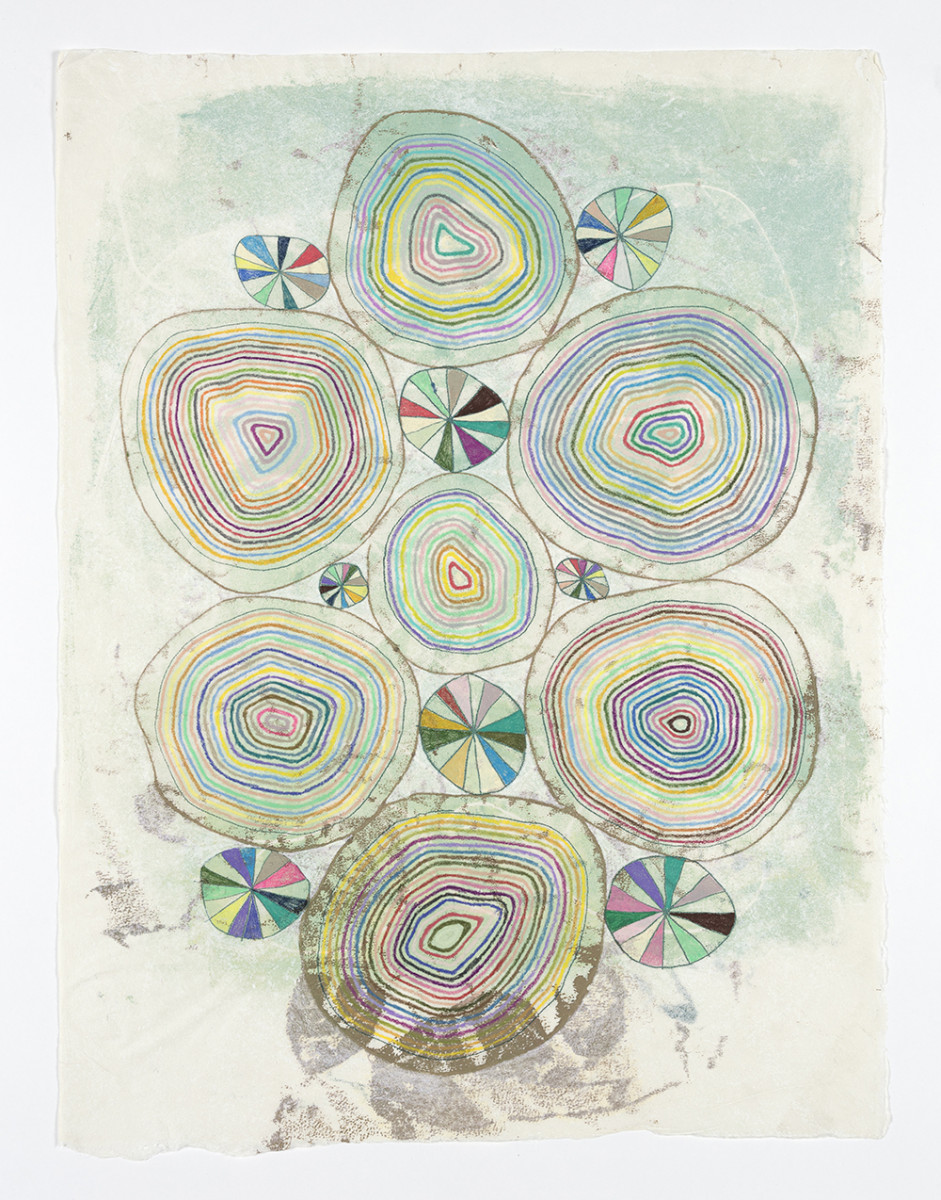

Steve Turner is pleased to present Mississippi Shade, a solo online exhibition by Jackson, Mississippi-based Claire Whitehurst that features new colorful paintings on paper which consist of imprecise concentric circles, intersecting biomorphic forms and cilia-like lines. Though her compositions might at first appear to be non-representational, they actually relate to nature and science. As someone who has lived most of her life in the American South, Whitehurst is especially motivated to convey the land’s internal psychology – the mystical more than the visible, feelings more than thoughts and sensations more than images.

Claire Whitehurst (born 1991, Baton Rouge, Louisiana) earned an MFA at the University of Iowa (2020) after earning a BFA at the University of Mississippi (2015). She has had solo exhibitions in New Orleans, Iowa City and Oxford, Mississippi. Mississippi Shade is Whitehurst’’s first exhibition with Steve Turner.

Claire Whitehurst in conversation with Steve Turner

Steve Turner:

We met in May 2019 while you were in the MFA program at the University of Iowa. I remember thinking that you were interesting and was curious to see how your work might develop. Here we are nearly two and a half years later, soon to open your first solo exhibition with us. A lot has changed since we met, but before we get to that, please share some background on yourself. Where did you grow up? Describe your upbringing and the circumstances that influenced you to become an artist.

Claire Whitehurst:

I know! I remember eating a sandwich with you in a huge booth. I’m so excited to be working with you again. You were pronouncing my name the same way my grandmother does: “Clayyyah”. You were spot on, and you didn’t even know it.

I grew up in the South. I was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and then moved to Jackson, Mississippi when I was about ten. I was mad that I wouldn’t have Mardi Gras break anymore and was confused by all of the churches. We grew up Episcopalian, which was the most relaxed of the southern religions. I didn’t leave the south until I was 21 when I went to Australia to do a college exchange program.

I have been painting for as long as I can remember, but I think it all started with loving mud when I was very young. I never wanted to wear clothes and would smear mud all over myself and anything around me. I got in trouble for eating art supplies in kindergarten and it took a long time to actually stop doing that. I think I’ve always been in love with material and the physical sensations of it and how that translates into emotion. My work and process is very synesthetic and I’m ultimately guided by intuition and touch. I sometimes think of the image as a sort of residue of touch.

Both of my parents are scientists and they taught me how to observe the world with intimacy and curiosity. I’ve always been interested in why and how things work. My studio operates as an experimental lab most of the time. Pouring one thing on top of another thing and seeing how it dries. Those interactions give me ideas for colors and imagery.

I also studied cave paintings in southern France as part of my graduate research which was a deeply meaningful experience. I was particularly interested in the relationship of rock formations and the selection of images. With the introduction of a small flame as a light source, drawings become animated and flicker. I like thinking of objects and images existing together in a flickering sort of way.

ST:

I love the wide range of Southern accents. I must have picked up on something to relax the “R” in your name. I think I also sensed something profoundly Southern about you. For the benefit of those who might not know what we are talking about, can you elaborate on Southerness, particularly the kind of liberal Southerness that you experienced. Are your parents both native to the South? From what you just said, I know your grandmother is. How long has your family been in the South?

CW:

Yes, my parents are both from Louisiana and their parents are from Louisiana. They’re very southern, and like you said, they are liberal. They are spiritual, not super religious, and they love where they are from. My mom went into infectious disease at the height of the AIDS epidemic and my dad is an environmentalist who fights off-shore drilling in the Gulf Coast.

Southerness is elusive and hard to pin down. For me, I wasn’t aware of my Southerness until I left and people would tell me when I was being “Southern”. It comes out in my voice, in what I know and how I’ve grown up. I think it comes down to knowledge and experience. For example, I was with someone who got stung by a bee and I found a cigarette and took out the tobacco and spit in it to dress the sting. I was told that it was southern.

I know the sound of a hurricane and what storm clouds look like and when to get out of the water. I can smell when a cockroach is near me. I can tell when the seasons are changing by listening to what is loudest in the trees. I hate sweet tea and have a visceral reaction to it. Many things all at once.

ST:

I think Southerners hold their origin more strongly than do people from the Northeast, Midwest and West. Southern food, culture, music, craft and folklore are so vivid. Every region has its idiosyncrasies, but Southerness seems most indelible.

Staying close to home, you went to college at the University of Mississippi. Did you study art there?

CW:

I think Southerners hold things closely in general, tight or loose, for better or worse. I continue to be drawn back over and over again even though there is a certain hauntedness to everything. The lushness and beauty of the south will forever be in stark contrast to its violent history. There are secrets and mysteries everywhere. It’s a strange place, but so much good art has come out of it.

I studied painting and printmaking and did a lot of ceramics at the University of Mississippi. I also worked at the art museum for a stint as an archivists intern. I got to catalog Egyptian IUDs and confederate army uniforms. You get to know a lot about a place when you dig through the things they keep.

ST:

It seems natural that you studied ceramics considering your early love of mud and the fact that George Ohr, the mad potter of Biloxi, produced some of the most captivating vessels ever created not far from your home.

When I think of Southern art I think of quilts, Gee's Bend and otherwise, face jugs, folk carving, Bill Traylor, William Eggleston, William Edmonson, William H. Johnson, and thankfully a non-William, Clementine Hunter. What good Southern art or artists are you thinking about?

CW:

Yes! I love George Ohr and his wonky vessels. I think about his work a lot. I also love Clementine Hunter. I got to see some of her work at the Ogden down in New Orleans over the summer. It was such a gift to see those again.

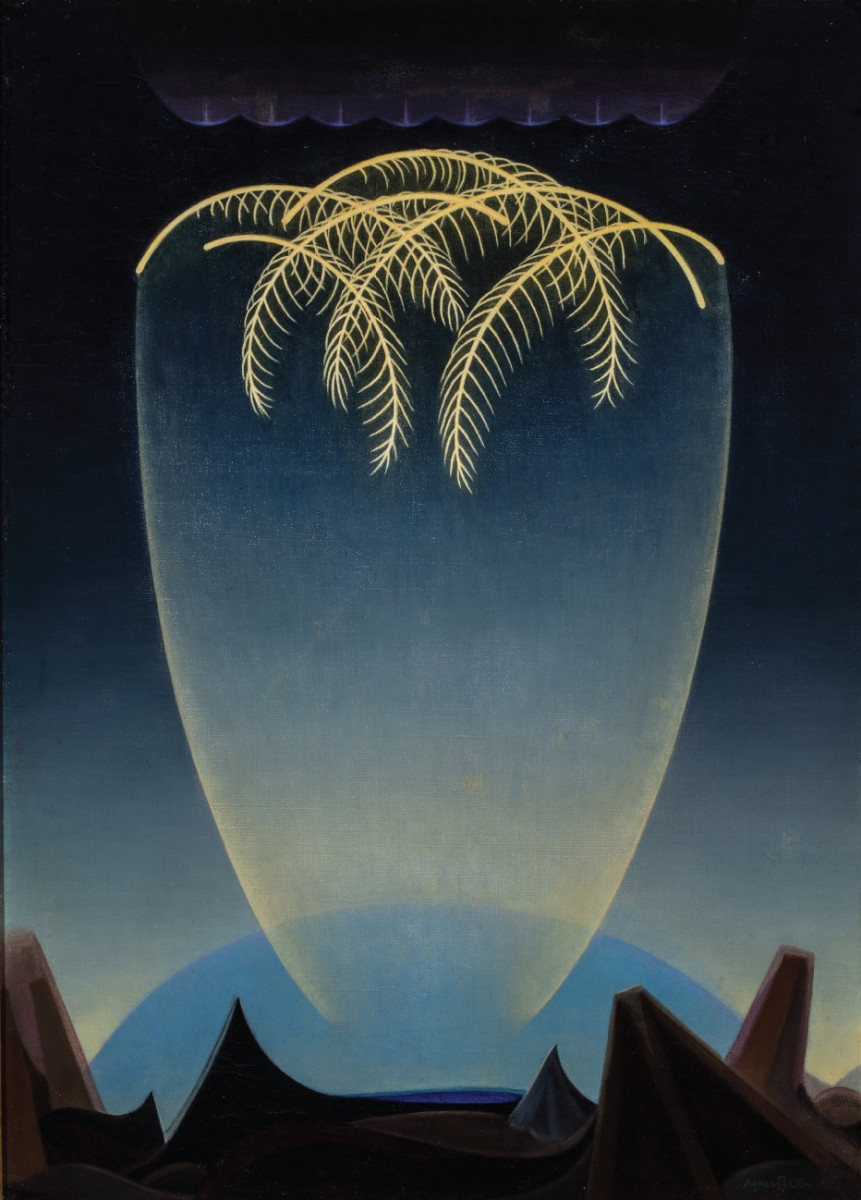

I have been thinking about Theora Hamblett a lot recently. She was a painter in Oxford, Mississippi and operated as a kind of mystical visionary. Often citing her own dreams and visions as plans for her work. Those dreams and visions also formally affected her paintings and how she split up space and used the rectangle to tell a story. The Mary Buie Museum where I worked in college had a huge collection of her paintings and I used to go back and pull out those big rolling walls and look at her work for hours. I also think about Sally Mann who is deeply Southern, but not from Mississippi. I was able to hear her read from her book Hold Still when I was in college, and I like the way she writes about the South.

Walter Anderson was also an influence from a very early age. He made paintings, prints, sculpture and ceramics in Ocean Springs, Mississippi, right on the water. He would row out to Deer Island during hurricanes and strap himself to trees to make paintings. His brother Peter started Shearwater Pottery and actually learned to throw on George Ohr’s old wheel given to him by his mother.

ST:

I find it interesting that both Hamblett and Andersen created images based on nature that push towards or have elements of abstraction. Does that ring true to you?

CW:

It does. I think that the Southern landscape easily pushes towards abstraction because there is so much embedded in it’s visual fabric. There’s something very intoxicating about the way growth and entanglement manifests itself during the seasons. There is an invasive heaviness to the trees, kudzu and native plants.

ST:

Who are some other artistic heroes, whether from the South or elsewhere?

CW:

I love Betye Saar, Louise Bourgeois, Rene Magritte, Agnes Pelton and Ruth Asawa.

ST:

Let’s leave the South for a moment. Can you share your experiences of going to Iowa City to get an MFA at the University of Iowa?

CW:

I think when I was in Iowa I realized how the landscape affects my work. The space was totally different there as was the temperature and air. I would just drive around for hours seeing what the landscape was doing. There are rolling hills outside of town and I loved being out there. It made me understand Arthur Russell’s music.

When I was in Iowa I used white and negative space differently than I had before. With snow on the ground for months, I had to learn how to maneuver in that environment and I think it affected the work.

I also met some of my best friends and got to work with so many brilliant people. I took seminars at the Writer’s Workshop and realized how important words are to me. I started writing and it felt good. I think that what I was reading and what I was writing became very lyrical and filled with space.

"Titles come about through the process of making. I have synesthesia so I experience taste and smell sensations

with colors and shapes."

ST:

On the subject of titles, here are some from your current show:

christmas lights underwater

cloud trapped in a toothache

the heat inside of a newly formed leaf

I find each work and each title to be evocative but am curious to know more about the relationship between the two.

CW:

Titles come about through the process of making. I have synesthesia so I experience taste and smell sensations with colors and shapes. I also associate letters and numbers with color sets, so most of the titling actually comes from the colors and what they bring to mind. It’s not easy to explain so precisely, but they just come to me and evolve.

cloud trapped inside a toothache, for example, makes my teeth hurt. It also reminds me of a book I had when I was a kid that was a collection of short stories where everything happened inside of someone’s mouth. Little teeth people lived in teeth houses with tiny doors and windows and pulley systems for getting water. I remember being freaked out by that at the time and it is something I’ve never forgotten. I pull a lot from imagined places, and some of those are from books I’ve read. I’m obsessed with magic realism, short form fiction and poetry. I like how rich an image can become with just words. I like even more the translation that happens in my head.

ST:

I get that the titles come about organically from memory, experience, image, color and line. Where do the images come from? How do you develop your compositions and make decisions regarding color? I am especially impressed with your ability to juxtapose dramatically spare passages alongside those that are dense and complicated. I also like the contrast between works along the same lines.

CW:

I think the compositions manifest themselves in a very similar way. I keep a pretty detailed sketchbook of shapes and drawings, and take lots of pictures of color combinations that I see as I walk around. I take those back into the studio and use them as expressions of form and color. I use printmaking and drawing when I’m working on paper to imitate the way paint functions in it’s masking. I let color and texture come through as reactions to the forms that I make. I liken my process to taking field notes and then coming up with experimental reports of my findings.

ST:

Do you characterize your works as abstractions or are they more a magical representation of nature, natural phenomena and science? When I look at your works, I think of snowflakes, spider webs and kaleidoscopic imagery. Does that make sense to you?

CW:

I don’t think abstraction describes well what I do, but I often have to explain my work in those terms, which feels like putting on an itchy sweater. I prefer to categorize myself as a magical realist, or perhaps as a representational surrealist, hah! I absolutely relate to the idea of magical representation of nature.

I think of diatoms and cellular structures all the time. I like to look very closely at things and think about how I would make a drawing of it without using any representation of the source imagery. For example, I love to translate the wild symmetry of spider webs into a hall of mirrors.

"Mississippi Shade makes me think of the light in Mississippi during the end of summer"

ST:

I know that you returned to Mississippi after some years in Iowa. How has that impacted your work?

CW:

Yes. I was in Iowa for four years, and the return to Mississippi has been interesting. I’m teaching high school at the same school I graduated from, so there’s a lot of emotionally surreal symmetry that I’m experiencing.

I had forgotten about the heat and atmosphere and some people asked me where I was from when I moved back because I had a midwestern accent which felt like a slap in the face.

I feel like I’m relearning a place that I had forgotten. I haven’t lived here in 13 years, so a lot has changed, but some things are still the same. Some of the old potholes are still here. The trees are the same, just a few inches taller, and a lot of the older places are still here. The big fat rain is the same when big storms hit, although the storms have intensified since I was a kid.

ST:

I understand that all the works in your show were created in Jackson. Can you tell me what Mississippi Shade, the exhibition’s title, means to you?

CW:

I went through a lot of ideas, but light and place kept coming back to me. Mississippi is where I live again and where I am looking for a shady place.

Mississippi Shade makes me think of the light in Mississippi during the end of summer which was when I made all the works. Shade makes me think of obstruction or interruption of space. A tree must be large to block out the sun, and this kind of disruption ties into the entanglement I find in the southern landscape, one that encompasses disorientation, elusive light and unchallenged growth. Shade also represents a safe harbor as it is a place for rest and protection.