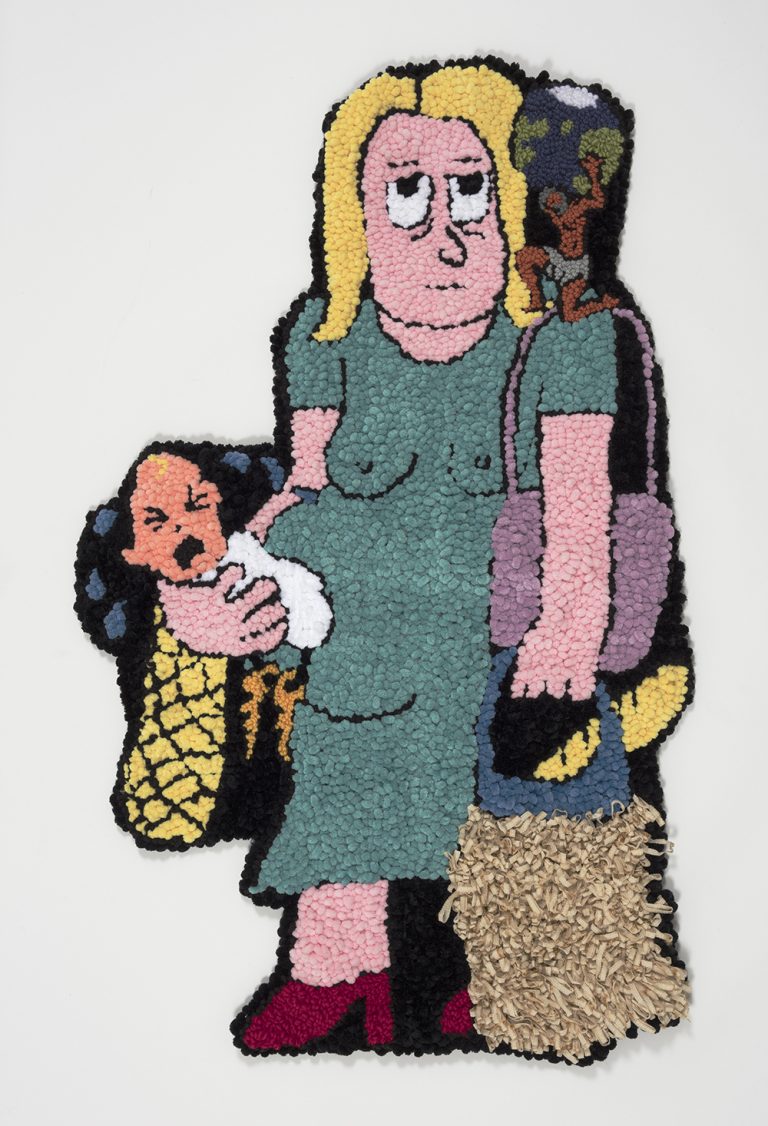

HANNAH EPSTEIN (born 1985 Halifax), grew up in remote Nova Scotia before going to college in even more remote Newfoundland where she studied folklore. After getting her MFA at Carnegie Mellon in Pittsburgh, she added conceptual rigor to her practice and became, as she calls herself, “a feminist folklorist of the internet age.” Her hooked rugs of monsters, internet memes and historically-inspired creatures are both humorous and disconcerting.

Hannah Epstein in conversation with Steve Turner

Steve Turner:

You have such a powerful source of energy, imagination and wit. How did this develop in Halifax, the place you once described as “a quiet rock in the Atlantic Ocean”? Can you share some details of your childhood that helped shape the artist you have become?

Hannah Epstein:

A couple of months ago, a man in Nova Scotia, who’d bought an old cop car at auction, used it to go on a killing spree. Cosplaying as an officer, he pulled people over and shot them, killing 22. He also torched a few houses and is now rumoured (far down the grapevine) to have used hand grenades during his chaotic rampage. I tell this story to try and impart that Nova Scotia, this bizarre little Canadian peninsula that sticks out into the North Atlantic, may be known to the world as some enchanting little tourist vista where you can get amazing lobster rolls and see live music in people’s kitchens, but to the locals, it is something else entirely. Scratch the surface and the place reveals a deep wellspring of weirdness that manages to bubble up in strange ways. The recent shooting is a very extreme example, but I am serious in saying it does capture something of Nova Scotia’s essence, many unexpected twists of absurdity, some violent, some good.

I last left Nova Scotia ten years ago but visited often to be reanointed by the ocean and the culture. Being here now, having “moved back” to escape the pandemic, I am beginning to focus on uncovering language and imagery that I can use to define the specific eccentricities of the place and infuse them into my work.

To answer your question, I think NS has operated on multiple levels as a source of inspiration.

It is the place where my family is, so all the peculiarities of family dynamics are present. Growing up, my parents were separated, living in houses right around the corner from each other, sharing a backyard. They remained in some sort of unclear (to me) open relationship.

My father is a well-read Jewish intellectual with a socialist ideology, which makes him an anomaly in WASPy Nova Scotia, where he somehow managed to keep winning elections as a lawyer-turned-enviro-activist-

My mother is an immigrant from Latvia who grew up in 1950s Canada, a place that didn’t appreciate being tall and thin with high cheekbones. She had a long and successful career as a librarian and spent most of it as head librarian at the Nova Scotia College for Art & Design (NSCAD) and is a textile artist, designing complex knitting patterns.

As the product of these two proto-hipsters I never felt penned in by any sort of dogmatic ideology. I was free to make “my own mistakes”. By sixteen I was living alone and fucking every guy I could get my hands on.

Nova Scotia has a thick layer of repressed Victorian vibes, so with my early decisions to be all free love and recycled hippie tropes, I felt scrutinized by neighbours and friends alike. I managed to find social pockets of other sidelined-types which sustained and inspired me. Like the Dharma Brats, kids of the American Buddhists, 60’s flower children, who followed their Shambhala leader, Chogyam Trungpa to the province and set up a range of businesses Nova Scotia had never heard of (including espresso-serving cafes and meditation centers). Like: the New Punks, boys who had legit good bands and drank Faxe and Golden Glow. Like: the less cool Goof Troop, wearing JNCO jeans, smoking weed out of glass blown pipes. Mostly wannabe goths since there was nowhere to buy goth clothes. Like: the kids from The Square, who were a mix of hood and hick. I orbited and traveled between these groups that formed a hotbed of culture in a place that always seemed to be straddling eras long gone.

I am back in Nova Scotia now and I am taking stock.

ST:

I usually have to ask a series of questions to elicit so much interesting information, but with you, all I had to do was turn on the tape recorder. You make my job very easy. Now that we know your origin story, let’s turn to your development as an artist. You are now well-known for your textile work. Was that something you learned in NS or was it something you learned when you went off to college to study folklore in Newfoundland?

HE:

I was fortunate to have always had art and artists present in my life. There was a kind of seamlessness to it. On weekends I would tag along when my dad visited one of his girlfriends, almost always artists. One made detailed landscape paintings of Nova Scotia wilderness and owned a parrot. One lived in a small wood house at the edge of a cliff and painted surreal interpretations of her small seaside village. One made scavenger hunts for my brother and I so we would be occupied outside. During the week I would see art students where my mother worked. They were like cartoonish background actors with their embarrassing fashion sense (skirts over pants wtf?!) and pretentious airs (where did they think they were?) and a constant source of mystery. When I visited the NSCAD library I would walk by the Baldessari print that hung near the entrance, “I will not make any more boring art” it read, over and over, and I wondered seriously what “non-boring art” was. I got my answer when I visited the Tate Modern for the first time (15 years old, father-daughter trip) and saw an enormous sculpture of an electrical socket hanging from the ceiling, probably an Oldenburg, it was so surprising and so not boring. Seeing that socket and later in the gallery, a leg sticking out of a wall, a Robert Gober, gave me the confidence to pursue my own divergent path, of which studying folklore was one of many steps.

Studying Folklore is oxymoronish in that folklore is, at its core, anti-academic. But the study of informal narrative culture and traditions, a.k.a. Folklore, formed the basis of my formal understanding of the culture of the fringes. It was only after I graduated that I further internalized what I had learned and approached a local rug hooker to teach me the skill she practiced. I had come to a point where it was no longer enough to observe, study and admire what people made in their “folk” traditions. I wanted to participate and work to reshape and elevate the practice, finding a way to turn it into a stadium style performance.

"I had come to a point where it was no longer enough to observe, study and admire what people made in their “folk” traditions. I wanted to participate and work to reshape and elevate the practice, finding a way to turn it into a stadium style performance."

ST:

This is before you went to Carnegie Mellon for your MFA, right? What images did you depict in your first hooked rugs? And, what other work were you making besides textiles? What motivated the various work you were making at the time?

HE:

I resisted any formal art education as long as I could, since I could see from early on that there was a predictable pattern to the “type” of person that chose to attend art school. Just as predictable, the work they would make. The predictability seemed jarringly in contrast with student aspirations to make work of note, since only work that radically diverged from the expectations and standards of its time made it into the library. Mostly students were trying to imitate what had been successful in the past with few aiming to be truly original. Anyway, I concluded that I had to champion aesthetics outside the official art history canon and develop my own hierarchies and that meant dodging art school until I had built that for myself.

After I finished my folklore studies and spent years traveling and working a variety of jobs, mostly around clubs and nightlife, and only after I had delved into the more obscure communities of experimental media and found a foothold in the world of indie games, did I think I was ready to attend art school.

The foundation I created for myself was “outsider art”, it was “folk art” and populist in that it valued “entertainment” as “artful” and incorporated personal narratives from friends, meanwhile it lived on platforms, like YouTube, which were all about a central hub for a variety of folk practices presented in video.

By the time I got to the MFA program at Carnegie Mellon, I was without any BFA grounding in artspeak and so averse to the formal instruction of art that I was resistant to accepting input from teachers and colleagues. Only recently, a few years post-MFA, do I feel like my work is starting to coalesce.

ST:

If you were so aversive to input, what then did you get out of your MFA experience? And, if you feel that you work has only recently matured, to what do you attribute that?

HE:

Before my MFA I was completely free floating in my artistic development. I would come up against the established art world only in peripheral ways. I began to feel limited in my ability to be recognized as an artist without the right paperwork, so I applied to MFAs. Being accepted into the program at Carnegie Mellon was an introduction into a world I’d largely only observed and it was a chance to put theories I’d been developing, like, the importance of having a unique voice vs. formal instruction, on trial.

I started the three-year program with an "IDGAF about your 'standards'" attitude to the work I produced and I think people responded to it, although with a lot of confusion. That initial burst reinforced my egomaniacal idea that I was beyond instruction, that I was there to act as a Trojan horse, bringing folk aesthetics into the academy. But as my time at the school went on, I encountered a lot of rejection of my work, and it did shake my confidence and I started to make work that tried to appeal to what I thought were refined, highbrow, art school sensibilities. The best thing I got out of my MFA was having one of my professors, Paolo Pedercini, call me out for trying to suck up to what the other faculty wanted from me. Being called out like that was the kind of conversation I had been craving, one that spelled out for me that the intent present in objects when made is “readable” by an audience and I was being read. I finished the program making work that invoked that original IDGAF spirit but was, hopefully, more effective than earlier work.

Making work since then has been a process of learning how to pull the reins that control my energy and trying to channel very specific moods and characters, instead of channeling haphazardly from the ether, which I have done a lot of. A lot. It’s been a process of coming into one’s own power.

ST:

I met you just as you were finishing your MFA at Carnegie Mellon in mid-2017 and I offered you a solo show right away. You opened Monster World in our third gallery room in January 2018 and it was quite a success. We sold nearly everything, to experienced collectors, to quite a few artists and you got a very nice review in the Los Angeles Times. How did it feel to have a measure of success so soon after graduating and what did you learn from the entire experience?

HE:

That was major. It was like the magic eight ball had been shaken and all signs pointed to yes. It was very much one of those cliche, “it’s a combo of chance and hardwork” lines people say, but that’s what happened!

After the dozen studio visits I had in grad school that amounted to nothing, it was the one scheduled out of the blue by my professor, Angela Washko (empress of digital art), with Ann Hirsch (priestess of new media), that led me to a connection with “Steve Turner”. In my studio I kept a wall covered with the dozens of rug hooked pieces I’d made over the years and Hirsch was drawn to it and sent me in your direction. My partner at the time was working in LA, so the next time I was in town, we arranged to meet. Everything had to line up, by totally unimaginable happenstance, and it did. I’ve felt incredibly thankful ever since, and I’ve been fortunate to feel a sense of receptiveness from the gallery audience. It all feels like an affirmation of my earliest intuitive feelings, that I had to follow my own path and trust that it would end up where I wanted. Having a successful solo show right out of the gate did feel like instant success on one level, but it had been a long, laborious process as well.

ST:

Monster World was a great way to introduce your hooked rugs to a broader audience. It was presented in one of our smaller galleries and there was a range of work, wild creatures and internet memes. Can you briefly describe the overall theme of the show and a few specific works?

HE:

There are a few works that really define that show for me. Of course Mouser, which was terrifying to step back from after making him, because he really felt alive and possessed by some demon. Also Making Fun Of War feels significant. The piece depicts an exaggerated version of a military ritual where soldiers carry around enormous swords, a real “culture of death” type of tradition, and it’s covered with these playful amorphous blobs who refuse to be afraid of the soldier and his death commander (comedy vs. war). There was also the piece that depicted the iconic moment of Britney smashing the car with the umbrella right after shaving her head and The Dream Of The Memelord’s Wife, where a hentai girl is being fucked by tentacles with the word “memes” tattooed on them. Finally, the three-panel comic of the man asking, “Am...am I...an animal?”, which also exists as an animated gif. All together they amount to a survey of what my inner life feeds on, a mix of memory, digital iconography, celebrity and the tabloid media assault, cartoon pornography and a conscious effort to subvert and dismantle all systemic conflicts with funny-haha antics presented in the soft, harmless form of a domestic craft, gone rogue.

As an introduction, Monster World was the groundwork that established expectation. This was the material (physical and conceptual) that I would be tackling. It would be like watching a media sausage factory stuff cut-up media bytes into their casing, a messy, multi-pronged progress with occasional intervals of Jolt Cola, but soft.

ST:

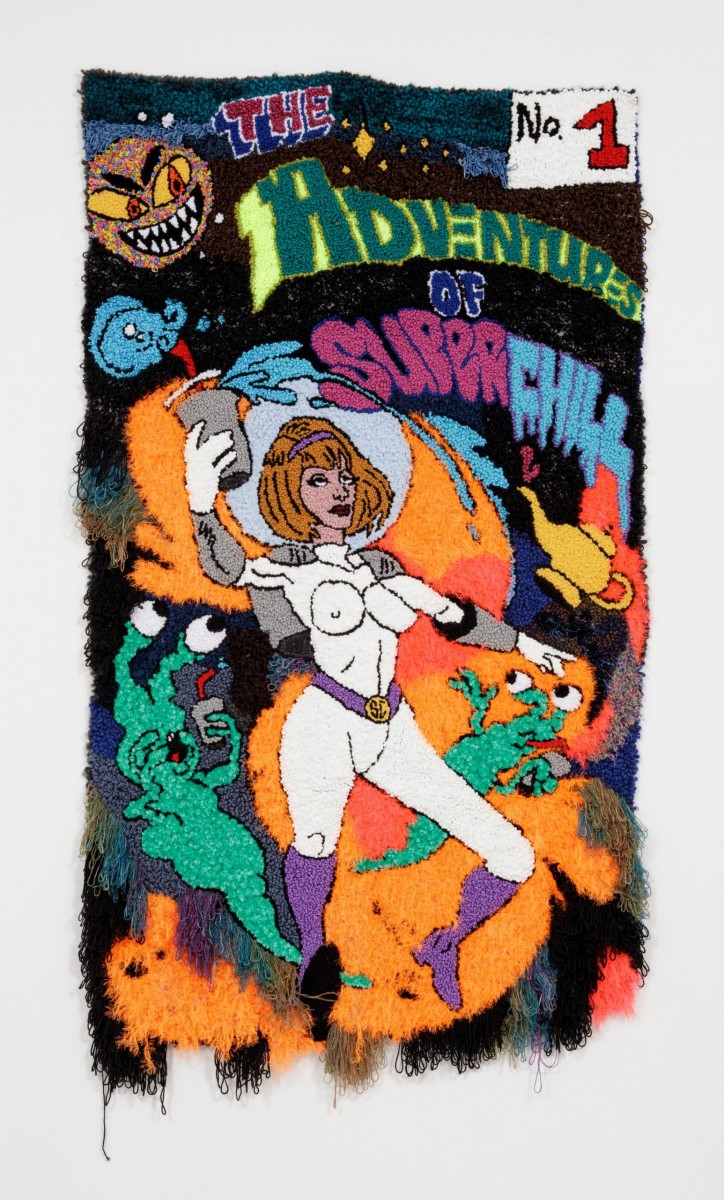

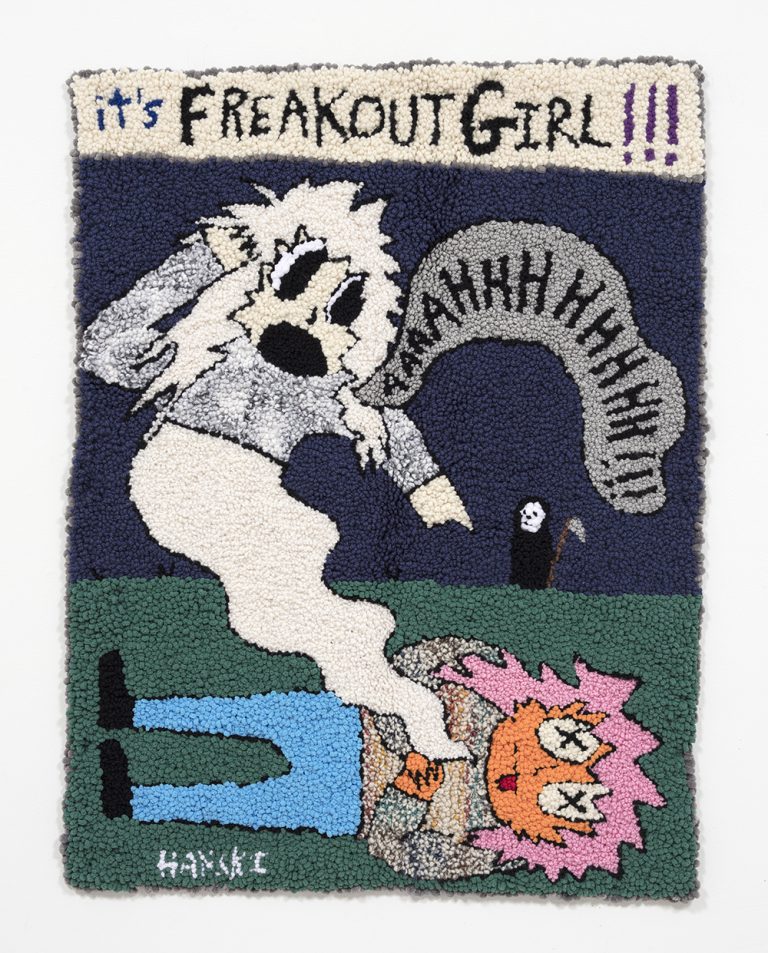

Your second solo show, Do You Want A Free Trip To Outer Space?, opened just one year later. You went from a small project in our third gallery to a large-scale immersive environment in the main gallery which included a hooked rug comic strip presented with video animations and a video game. You introduced some new characters, “Superchill” and “Freakout Girl.” Can you describe the narrative of your comic strip and your motivation behind the show? And, might we expect to see more of Superchill and Freakout Girl?

HE:

I’ve been reading about tulpas, which are supernatural beings manifested through focus and meditation. Superchill, the embodiment of perfect chill, and Freakout Girl, the embodiment of chaotic freaking, are tulpas of a sort and they drove the creation of that show. Their clearly defined personas put them in the bracket of mythological figures (basically order & chaos) Together they represent the key balancing energies in a larger project: writing a new folkloric framework. It’s a funny, futile and egomaniacal task to be possessed of any intent to create the characters of new mythologies in the hope that they eventually supplant everything we currently know. Not because the task itself is absurd but because that project is already taking place on the internet through memes and the authorship is appropriately collective. Despite that, I still think the art world is a place to foster myth creation, and that’s what the Superchill and Freakout Girl comic is doing there.

The show opened in early 2018, two years into Donald, two years into the alt-right/antifa media war. The tensions were wicked, had been, and everyone was clique-ing up hard. You were/are either with the Jets or the Sharks. Long winded Atlantic think-pieces are The Jets and long winded rants from Alex Jones on InfoWars are The Sharks. The art world, mostly Jets, probably, was/is not immune and many of its highest regarded publications were making their anti-Trump, anti-populism opinions clear. Later that year, Boyd Rice’s show was cancelled at Greenspoon Gallery in NYC after a threats taking issue with his neo-Nazi-like aesthetics were directed at the gallery. I just hate that kind of shit. The censorship over these issues that feel so sensitive we must keep them locked away and never learn how to sensibly address them and find *gasp* resolution, no, fuck that. So anyway, making work in some of the shittiest time in human history (as seen through my millennial lens), I was like, “I can be like all these predictable charlatans who seek to make their political puritanism their entire brand, or I can quest to find a creative path through the thicket of conflict.” Superchill is my machete.

I’m not sure if Superchill is an enlightened Buddha or super depressed nihilist, but there is nothing on earth or in space that can shake her sense of utter chillness. Point in case, in the second solo show, we follow Superchill on her free trip to space offered by some unseen benefactor, probably Musk. The ensuing comics portray a laid-back adventure, as every creature she encounters is pretty much as chill as she is, which is its own idea; if you feel chill, so will the world around you (as above, so below, as within, so without).

When I started posting about Superchill on my Instagram I was instantly attacked by a fierce feminist voice in the comments section, calling me out for being another pusher of the “cool girl” narrative. I then went on a long internet recon mission to learn about the “cool girl”. And like, theories about how the idea of a “chill” female is an act of erasure because it’s a nerdy male fantasy aside, I was dismayed that the character I had created aa a beacon to chillness was already causing a fembot to freakout. So Freakout Girl, the girl with the power to freak out about every single tiny thing, came to be. The idealogue feminist can have her totem and I can go back to working on Superchill.

The animated, immersive and interactive elements of the six-projector set up were the icing on the new mythos cake. I’m running a propaganda machine, too.

Will you see more? Definitely. These tulpas exist in reality, it would be rude to ignore them.

ST:

Your most recent solo exhibition, Making Bets In A Burning House, opened in February 2020. This time you had two galleries within which to work and each included a range of work within a room installation. What was the essence of each room and what was the dialogue between the two?

HE:

In this show, one room is on fire, the floor has become lava and you are surrounded by messy, handmade memes, characters and symbols from personal narrative. There is almost no solid ground on which to stand as the walls feel like unscalable prison blocks – end times energy. The second room is trying to make a comfortable space out of a secretive surveillance system, the replacement of human artists with AI generated art – a world devoid of the human hand. Except for one mischievous Soft Worm, my snake in the post-scarcity garden. Overall the show is a type of breaking point.

The dialogue between the two rooms is one that is emblematic of the push and pull of two realities in this tumultuous time of transformation. Of course I didn't know there would be a virus vector as part of all this, but the new level of transition from the IRL human scale to the detached techno-dystopia of the post-scarcity world, where people no longer work and all our leisure is surveilled, was inevitable before the coronavirus hit.

One of the key pieces of the show for me is Nerd Smasher, in the first room, where a cartoon woman with no hair is playing a video game where smashing nerds isn’t just the name of the game – it is the game. It captures the sort of disdain I have come to feel towards all the giants of the technological landscape and their utter fucked up selling out of the potential utopia that was online existence. They’re all just dorks to me now, their mystique fallen away, and a return to them being sidelined as such is a relief, like how did we all get cucked by nerds? The promise of Like A Dragon U-furled Its Wings, the ten-foot dragon flying around the room, is that we will remember our innate unbridled human powers, like an updated dream of a working class revolution, where the kids in athleisure decide to wear Phrygian caps.

In the second room, where you can sit on a green carpet covered in pillows and watch people stream through the first room via live surveillance footage, I am most happy with the pieces generated by an AI neural net that predicted my future output. As much as I desire to slam everything that reeks of high tech gloss, there is an element of collaborating with an algorithm that has a unique texture and I will be casually considering the results for a while. Not to go unmentioned there is also the cum towel of Jizzus Saves, that depicts Jesus on the cross cumming on “society”. The image was illustrated with a program that recreates rug hooked patterns I’d developed, trying to find ways to replicate my rug hooking texture.

Like the title suggests, we’re all making bets in this burning house (global warming, pandemics, general apocalypse in all directions), despite the horror etc. because reality is shapeshifting in all directions, and anything is still possible. Which I’m excited about in a tired and exhausted type of way.

ST:

Unfortunately, the show was prematurely shut down by the onset of Covid-19. I wonder how the pandemic has affected you. Can you describe your most recent works, the ones you have after your exhibition closed?

HE:

The pandemic is fresh and so I’m just going to write from the thick of it.

I bought a car back in January and drove it from Nova Scotia to Los Angeles to do the install for the show and enroute the #coronavirus news started streaming out of Wuhan. It looked scary as hell, all the shaky leaked camera footage of bodies piled up in hospital hallways, people fainting in the streets, being carted away from airports in plastic bubbles, just a total nightmare. And I was like yes, universe, I know this virus is about to do such damage, but can it please hold off until like, after Yung Jake and I have a killer opening for our shows? Thanks. Then I bought a pair of elbow length black gloves to wear to the opening as some kind of virus prophylactic but the “numbers” were so “low” I was like, “fuck it” and just went out and partied that whole week (sans gloves). With ALAC, Felix, etc. it was a fab feeling to be in LA and it felt like I was getting my fun in before the whole thing really blew up. After the opening I drove back to Canada where I’ve been hiding out and going through a mix of raging out, freaking out, chilling out, blissing out and sometimes even forgetting about the plague and then remembering again. So, I was disappointed the show had to close early, but I’m happy that the old normal could attend the opening.

The works I’ve made since arriving back in Nova Scotia are currently in a big pile near my kitchen. It’s a really inconvenient spot for them, but they just keep stacking up, each a document of a moment in this ongoing snoozefest of a foundational transformation of all levels of society.

The first, currently untitled, is a piece about Grimes’ Miss Anthropocene album and Elon Musk’s SpaceX and the two of them as mass murdering billionaire art-adjacent villainous forces. The second is a hit piece on the CCP and their coverup of the virus, followed by a Freakout Girl episode where her ghost is encountering her own corpse and smaller piece of Mickey Mouse with a giant boner wondering if he’ll ever have sex again.

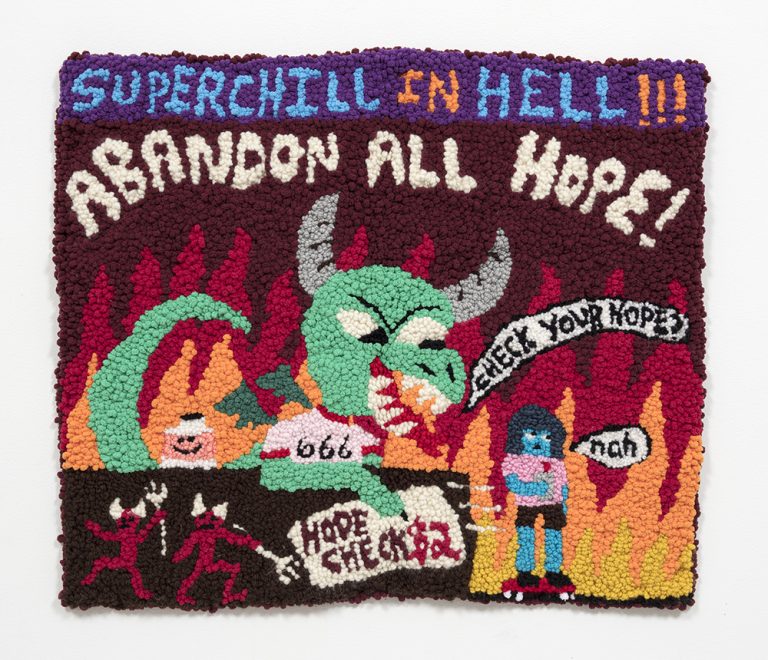

Those initial big bursts of angst aside I recently decided it was time to start working on Superchill in Hell, an idea I’d started to sketch out a year ago as a sequel to her trip to outer space. So, as promised, she’s back and she’s still super chill.

ST:

You have had a very busy two and a half years. What have you learned about being an artist?

HE:

I am now trying to focus on the very specific things that worked for me to get to this point. The largest takeaway I have at the moment is the immense importance of trusting one’s own intuition, despite whatever “rational” minds might tell you. I have been spending a large part of this quarantine time trying to refine the relationship I have with that intuitive voice, make it stronger, and build my ability to trust it. I now have enough experience that I can look back and see where trusting it made my work stronger and where doubting it made the work fall apart. It’s a constant dialogue I am having with myself.

"The first, currently untitled, is a piece about Grimes’ Miss Anthropocene album and Elon Musk’s SpaceX and the two of them as mass murdering billionaire art adjacent villainous forces."

ST:

Might we see some of these in your solo booth at Enter Art Fair, Copenhagen, August 27-30? Can you describe them? I hope you'll give equal time to Freakout Girl.

HE:

Yes, for sure. The saga of Superchill and Freakout Girl continues with each character's separate journey into the afterlife. Superchill goes to Hell while Freakout Girl finds herself in Heaven. Their stories are told episodically with a comic dedicated to moments in each character's adventure.

One irregularly shaped comic follows the movement of Superchill, like in an animation, as she skateboards along a residential street. Distracted by a bird she then falls down a dark tunnel into the underworld where she lands with a *thud*. In Superchill fashion she is unbothered and continues to slurp her drink into the entrance of Hell.

HE:

The next comic is a single panel of Superchill passing by the "Hope Check" counter where a demon asks her to check her hope. "Nah" she says, skating on, disobeying the only rule that Hell demands of it's visitors: Abandon All Hope!

Superchill is subversively condemned. In a comic where demons attempt to torture her, she refuses to react, quoting a Buddhist philosophical statement that "All existence is suffering". The demons hear this and realize that the suffering they inflict on others is tantamount to their own suffering and begin to cry.

HE:

While Superchill chills in Hell, Freakout Girl confronts her own death, first as a ghost exiting her body, then in Heaven, where the realization of her new reality is so horrific that not even the promise of everlasting peace can quell her. She runs screaming from the panel, breaking out of her comic frame conventions.

A separate, single panel comic, shows Freakout Girl falling from the sky, headed straight for Hell.

Once in Hell, Freakout Girl, known for catchphrases like "AAAAAAAHHH!" and "Not this again!", "Oh no!", and "Fuuuuck!!!", finds herself surrounded by creatures that mimic her wail of constant freaking. By the end of the comic she seems to have become bored with the echoes of her own horror and we see the first shades of a multi-layered Freakout Girl.

HE:

I was asked by a follower if Freakout Girl and Superchill ever meet. It's a question I had been unable to answer because I was still deciding if they were the same person or definitively different entities. The last few comics of the story investigate that.

Superchill and Freakout Girl encounter each other in Hell and the reader discovers a longstanding tension and resentment between them. Each is bothered by the other's personality, so different from her own. They share a thought bubble and think, "this bitch".

The final comic sets it up that we are in for a battle of the century, Superchill VS. Freakout Girl! They trash talk each other and then, instead of the expected climactic blow out between these two superheroes, we see that each is standing in their bathroom, looking in the mirror, and seeing a reflection of their opposite. Freakout Girl sees herself as Superchill and Superchill sees herself as Freakout Girl. This final frame still refuses to explain is they are one in the same or two individuals, regardless the characters themselves have been complicated for the reader as their inner life reveals a more complex struggle than their superficial presentation.

ST:

And how do the other works in the booth relate to Superchill and Freakout Girl?

HE:

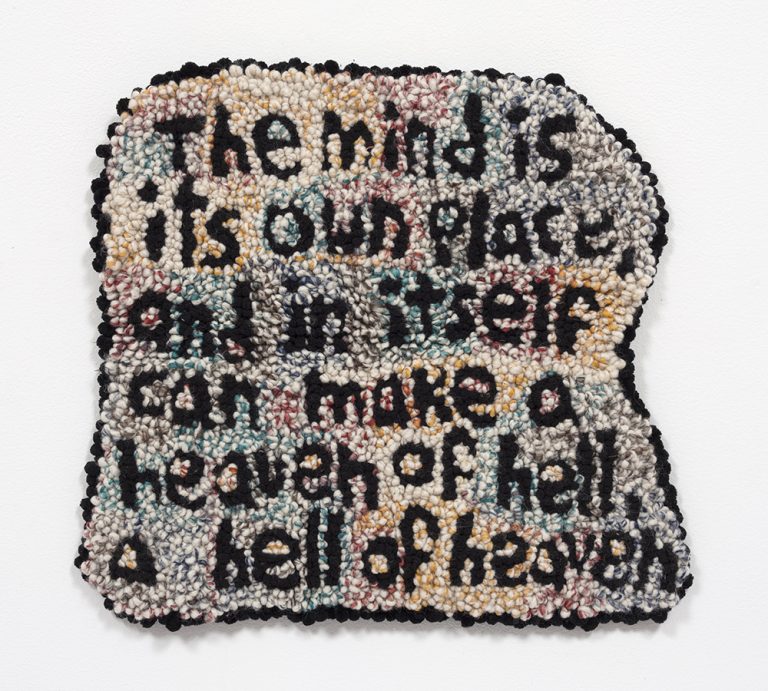

My other works in the show are meant as accompaniment pieces to the Superchill & Freakout Girl narrative.They provide glimpses into other characters present in the worlds they move through, characters who may have their own comic panels- yet to be made, or up to the viewer to fill in. One is a direct quote from John Milton's Paradise Lost, "The mind is its own place and itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven", which directly feeds into the duality (multiplicity, really) of the self, which holds the potential for all things.

ST:

I always love your titles. Do you have a title for your solo Booth?

HE:

Of course I do. See You In Hell.

ST:

Fabulous. On that note, I wonder if you might reflect on all you have done in the last few years. What have you learned about being an artist?

HE:

I am now trying to focus on the very specific things that worked for me to get to this point. The largest takeaway I have at the moment is the immense importance of trusting one’s own intuition, despite whatever “rational” minds might tell you. I have been spending a large part of this quarantine time trying to refine the relationship I have with that intuitive voice, make it stronger, and build my ability to trust it. I now have enough experience that I can look back and see where trusting it made my work stronger and where doubting it made the work fall apart. It’s a constant dialogue I am having with myself.

Please direct inquiries to:

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la