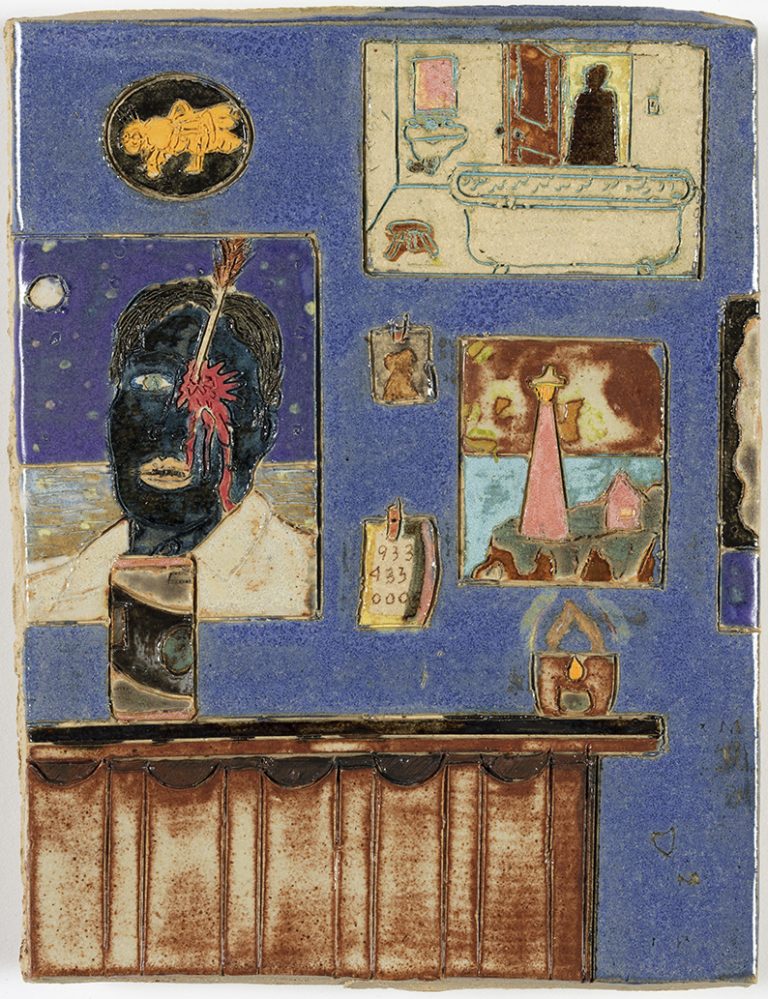

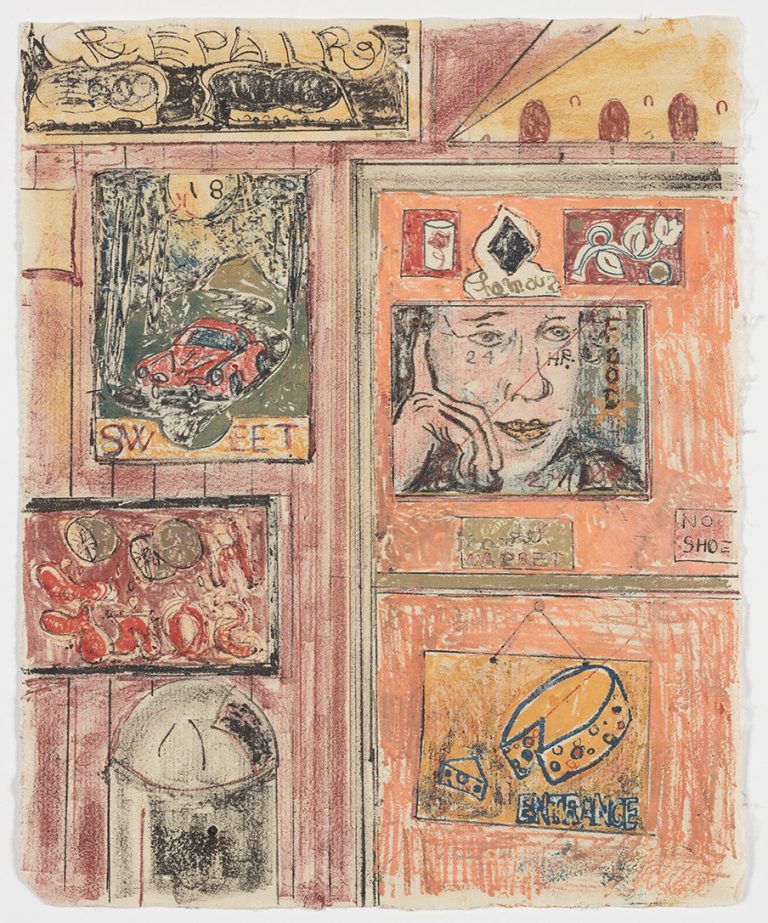

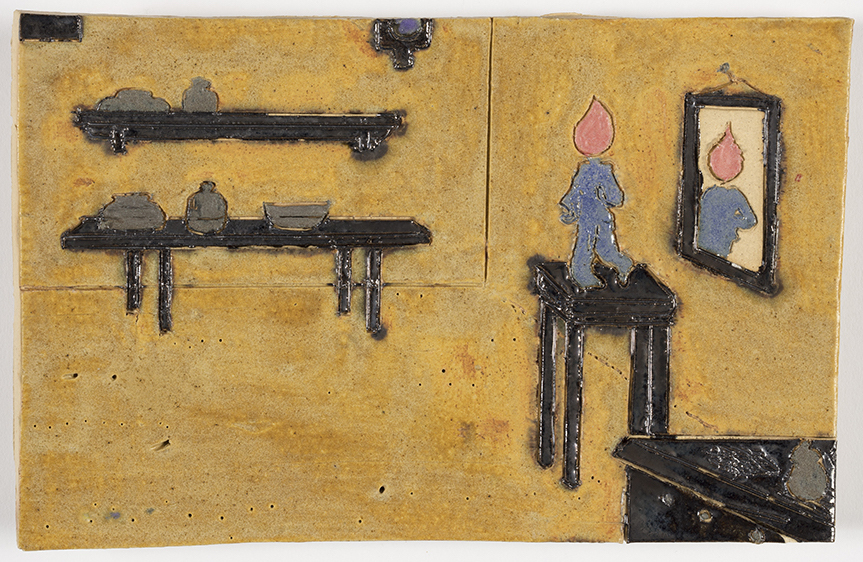

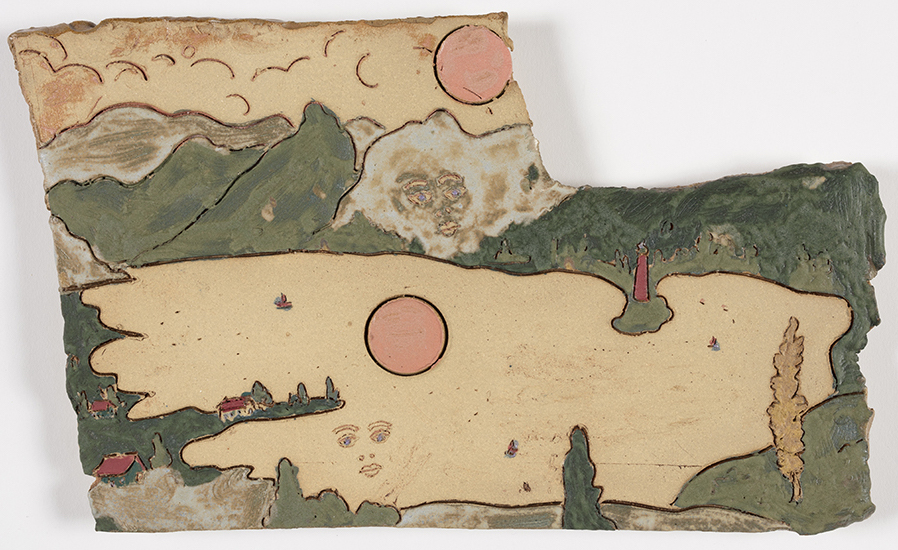

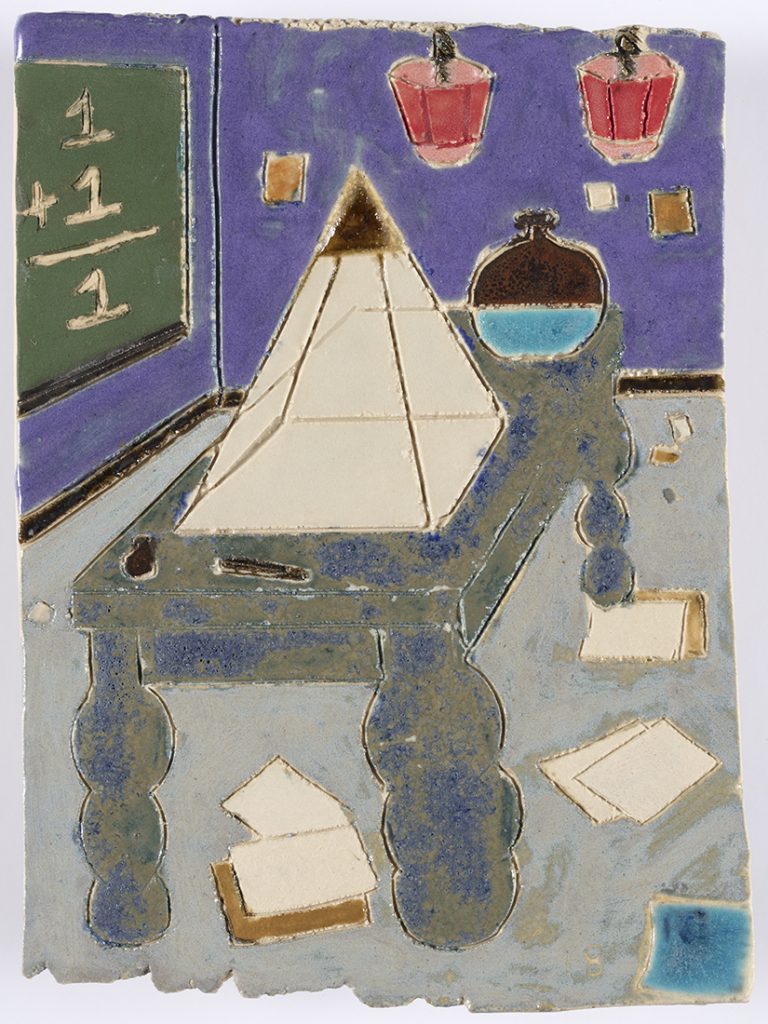

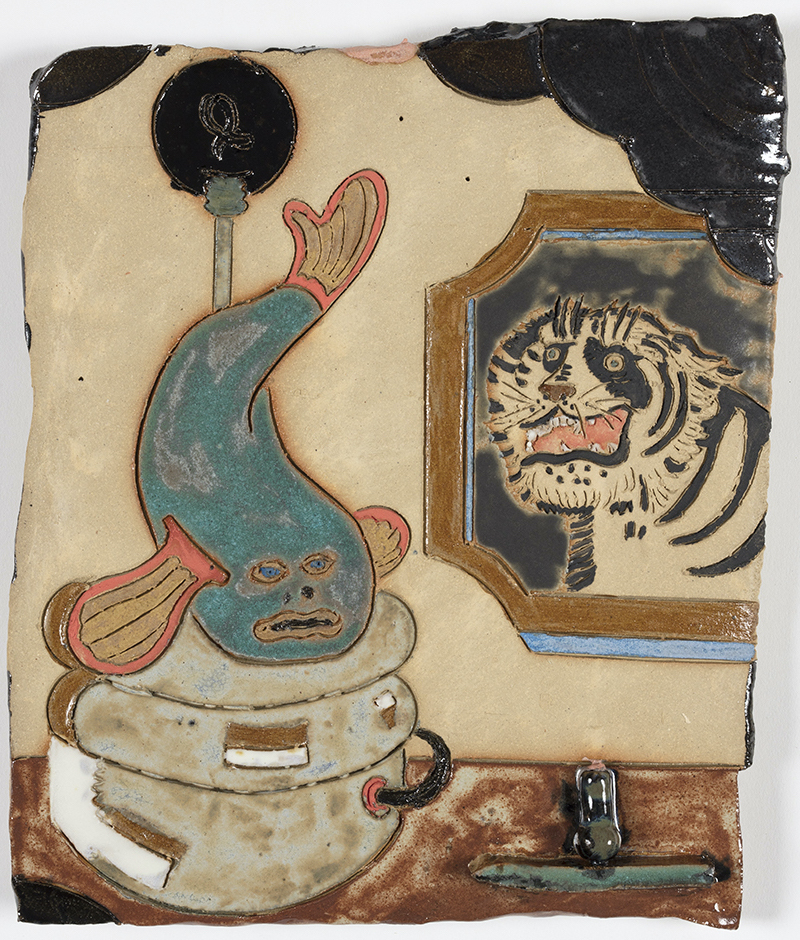

Kevin McNamee-Tweed (B. 1984, Stanford, California) has a multifaceted studio practice for which drawing and humor are central. Sometimes he draws on paper; at other times he incises a drawn line into clay, adds color with glazes and fires the clay to yield a ceramic painting; at other times he uses ink, a sheet of plexiglass and a sheet of paper to create monotypes; and at other times, he creates paintings that also incorporate drawn lines. Most of his works are modest in scale, often not much larger than a sheet of paper. But they are not paper-thin. They have depth and weight. His ceramic paintings are like tile fragments and his monotypes are typically mounted to wood which has stained edges. As a result, both feel like books, a category of object that McNamee-Tweed values above all others, including art. Whatever the materials and processes, it is the right combination of humor and beauty that makes his works stand out.

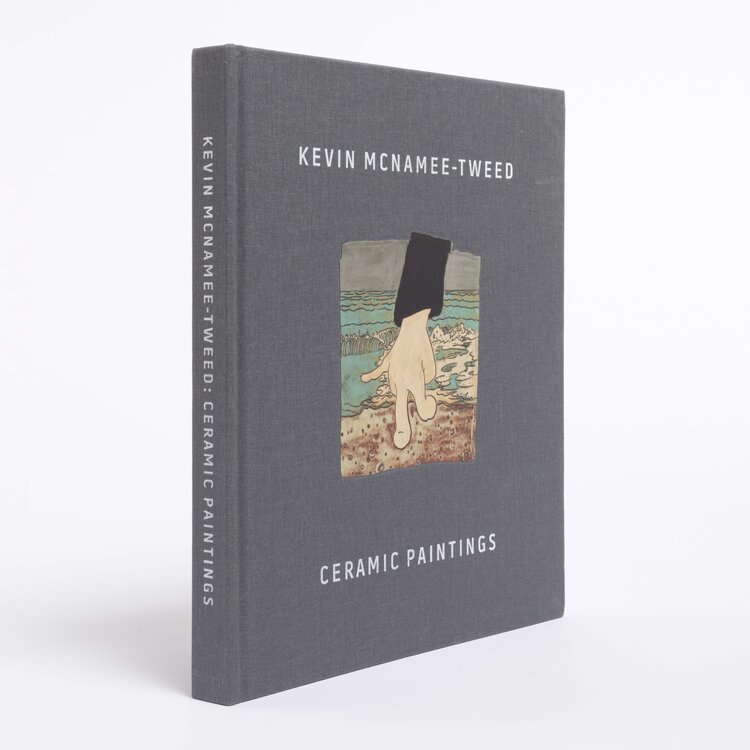

Steve Turner Gallery has published three books on the artist. Click here to purchase.

Kevin McNamee-Tweed interviewed by Lauren Moya Ford

From Ceramic Paintings, 2020 a monograph featuring McNamee-Tweed’s ceramic paintings of the last three years.

I met Kevin in Austin the night before I moved to Spain. It was a quick hello followed by months of emails back and forth about what we were thinking and what we were making. We saw each other again almost a year later, when I returned to Austin and Kevin was curating an exhibition of my work. I remember a hot afternoon looking at his jam-packed studio walls, and another we spent kicking a soccer ball around the gallery before filling it with things I’d made since we met.

That was nearly five years ago. Since then, we’ve followed each other in one way or another. Most recently, I missed him by just a few days on his first trip to Madrid, where I’d been living.

Kevin has an encyclopedic accumulation of images that work like words: sharp enough to state facts, yet sensual enough to conjure a memory. They come from the world he knows as well as his extraordinary imagination.

From the first color block canvases I saw in Austin to the curious new ceramic pieces, I was delighted to watch Kevin’s work develop. While his pieces and processes may seem disparate, they are ultimately connected by the artist’s quest “to find and depict a moment worth freezing.”

I looked through the numerous emails we’ve exchanged over the years and found a few points to discuss further.

LMF

In one of our earliest exchanges, you mentioned Roberto Bolaño. I always think about how Bolaño wanted to be a poet, but became known as a prose writer instead. Do your separate practices—secret or even failed ones—factor into the way you work?

KMT

I always think about writers who wanted to be painters. I feel a little lucky that I don’t feel like a poet or a painter, definitely not a novelist and only an artist by some coincidence and chaos. I was just reading an interview with the poet Anne Carson, who wanted to be a painter. When asked for a definition of poetry, she says, “If prose is a house, poetry is a man on fire running quite fast through it.” I wonder what painting would be in that scenario.

This is all to say, it feels quite arbitrary that I’m working mostly as a visual artist. I’ve been joking that I’ll become a marine biologist in the next few decades but it’s not really a joke.

I feel I anchor myself in the basic assumption that all these research practices, from science to math to visual art to literature to religion, operate on the same plane. So, to answer your question, yes, definitely, they are all present in my practice, all the failed, secret, future, distant, and hypothetical pursuits are active in this pursuit of creating objects and images.

LMF

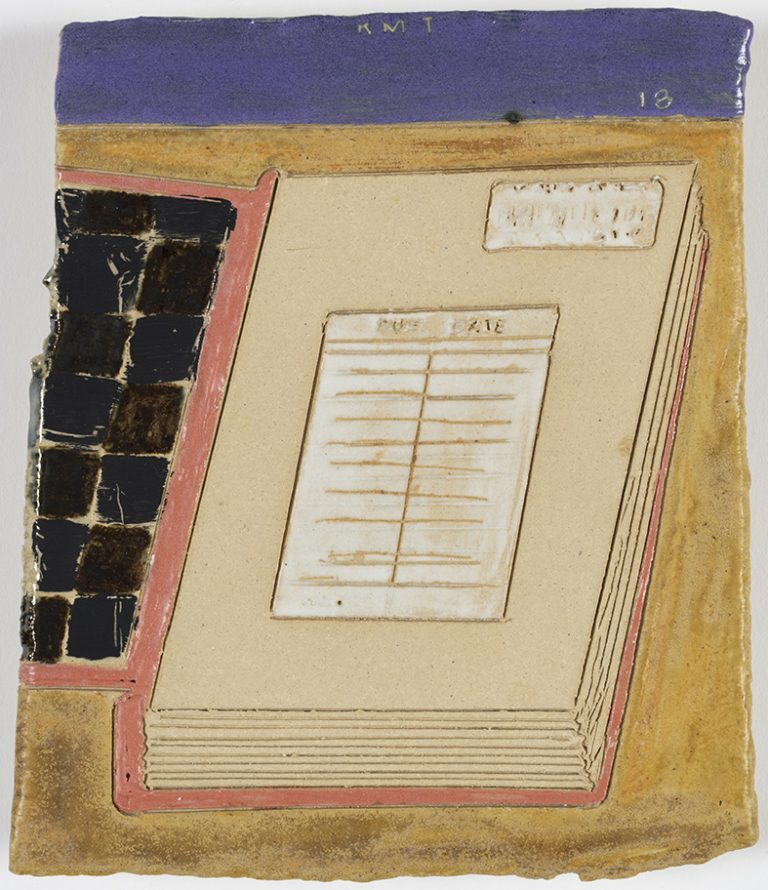

In a 2016 email you say, “Books keep being a part of my life in all sorts of ways.” Is this still true? What is your relationship to reading, and do you write?

KMT

I read in an idiosyncratic way which many writers will cringe at, I imagine.

I read about twenty-six to fifty-five books at once. My bedside tables are tectonic landscapes of reading material, constantly shifting and sliding. Sandwiched between books of poetry, fiction, theory, and art, are my notebooks, which tend to get shuffled quite freely. My writing is fragmentary and brief, rarely reaching a point of being “finished.” This is also how I read.

Books are, of course, very much another matter than reading and writing. Although I might argue that they should not be.

LMF

What do you mean?

KMT

Well, books have the curious privilege of being physical objects. They must reckon with being looked at and held, carried in bags and thrown on bedside tables. They cast shadows, are subject to the changing light of our days, their bodies become cold and stiff in winter. That’s all.

"I read in an idiosyncratic way which many writers will cringe at, I imagine.

I read about twenty-six to fifty-five books at once. My bedside tables are tectonic landscapes of reading material, constantly shifting and sliding."

LMF

Your pace of reading reminds me of the book I found at the apartment I’m staying at. I’ve completely disappeared into it. The pages fly by and I’m engrossed in a way that I haven’t been since I was about the protagonist’s age, an adolescent. So what makes you start and stop when reading?

KMT

I pick up books out of habit, out of simply wanting one in my hand and in my company. I find it hard to read usually. I just get distracted: by something in the text, or in the way a word looks, or how the paragraphs occupy the page, the negative space. It’s as often that I am catapulted into thought by some idea in the writing as

I am just engrossed in the act of looking. Other times the distraction is tactile. Sometimes the weight of a book is so perfect, the pulp of its pages so pleasing, the physicality so exquisite that I just sit and hold the book without any attempt at reading.

Often, when I do actually read, I don’t read because I want narration or stories or information in a verbal package. Rather, I am usually looking for an atmosphere in which to think my own thoughts. A new backdrop, new narrator, new voice, characters, new drama, new history to enact thoughts within. There is a chance I will think something I’ve never thought before. I stop reading when I realize I haven’t been following the text for some time and I must fall asleep.

LMF

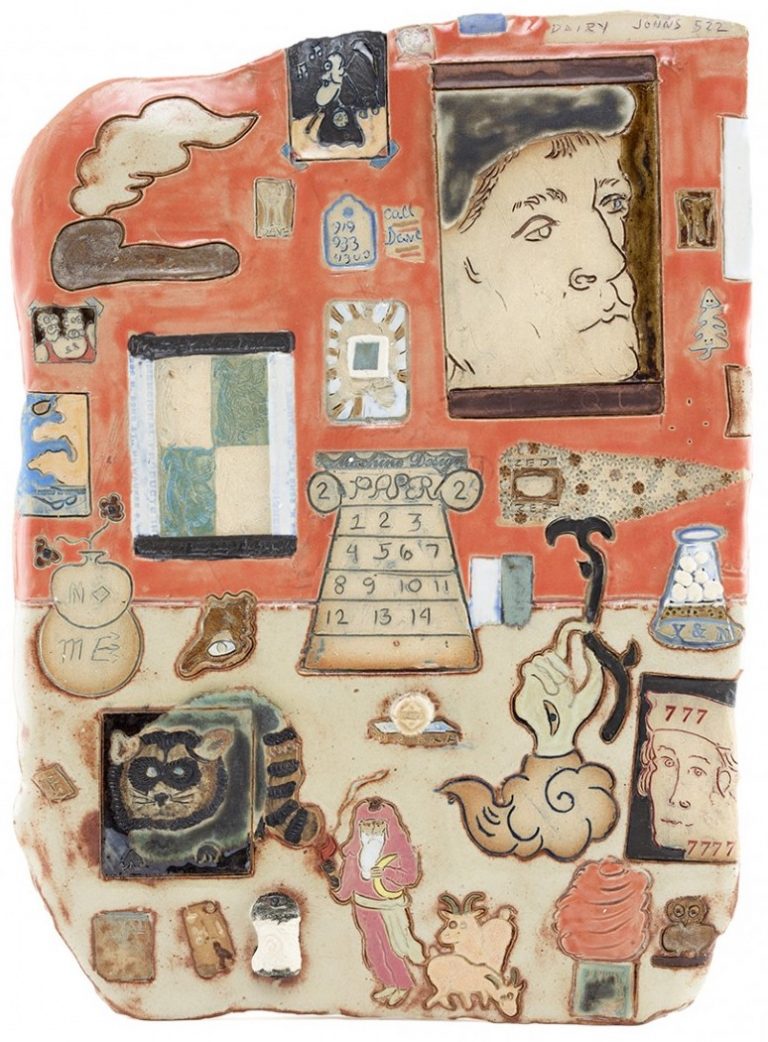

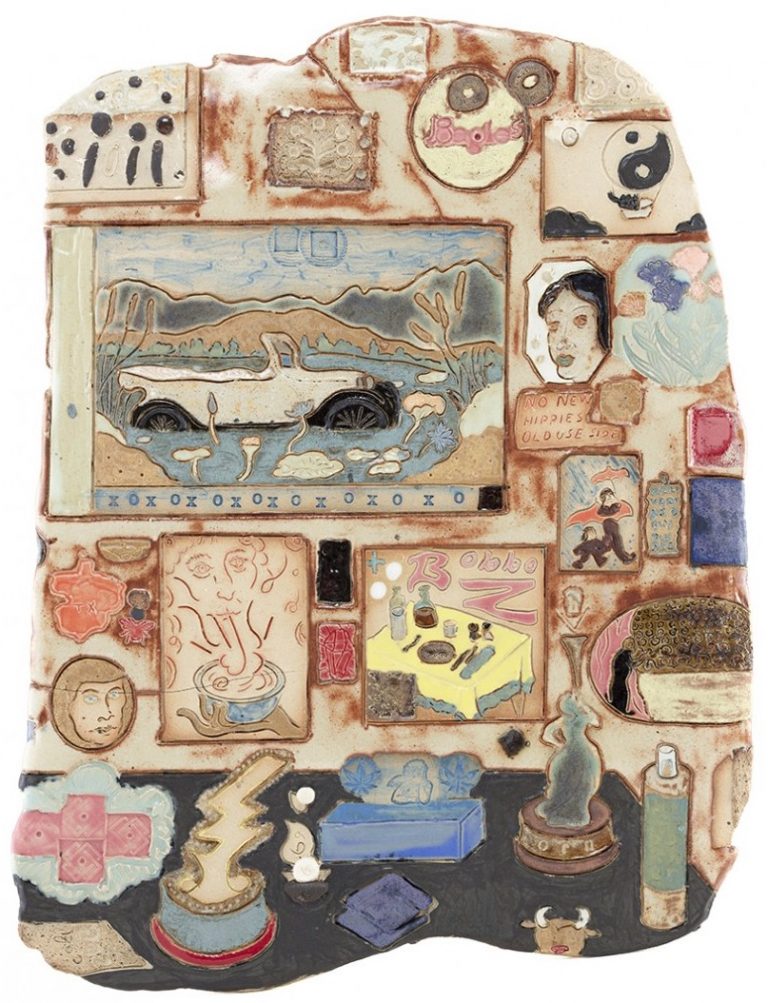

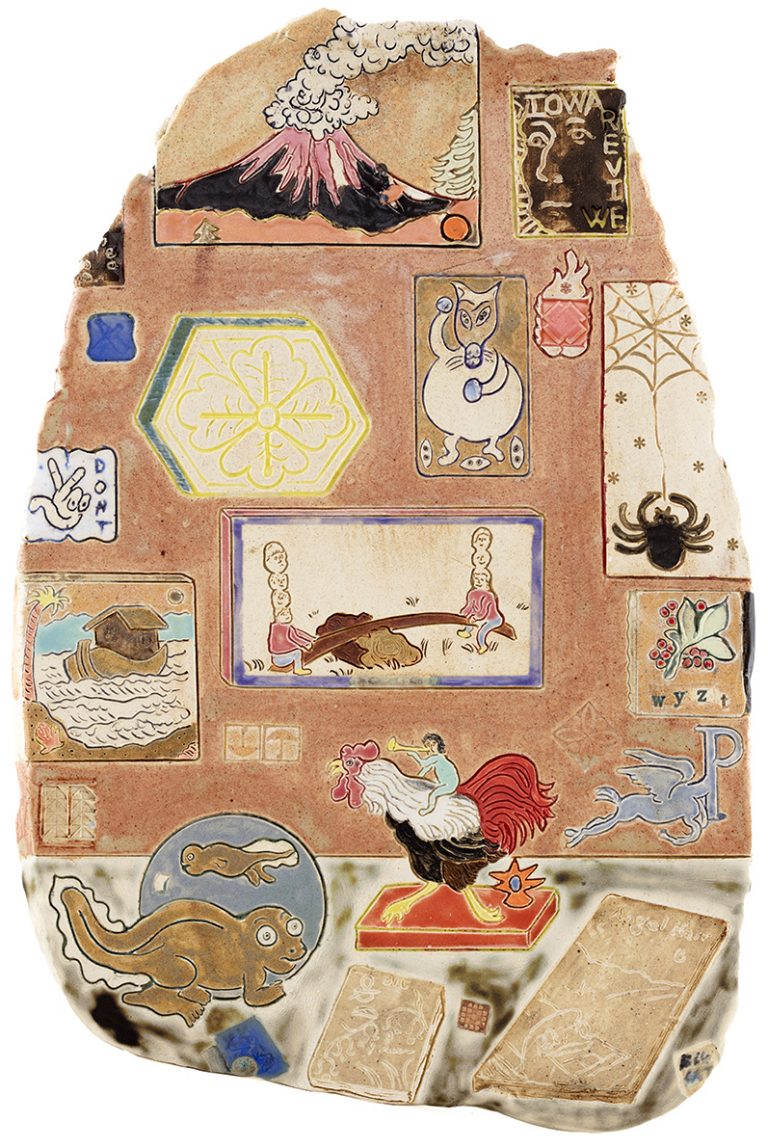

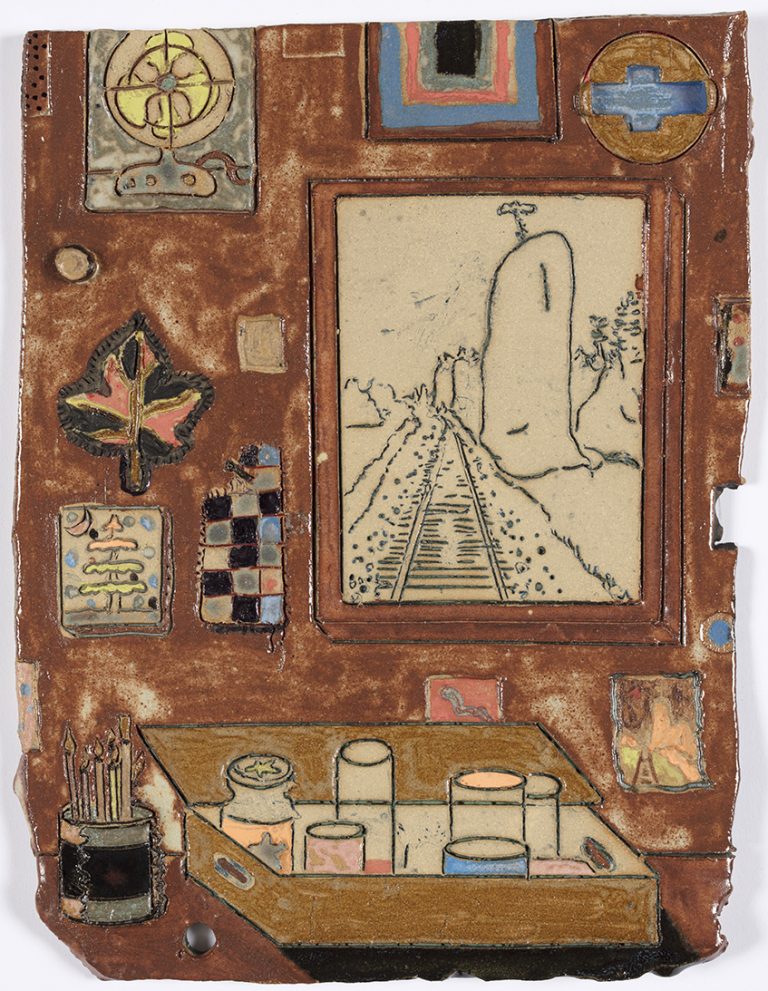

The many books on shuffle also reminds me of your works that contain multiple pictures inside of them. They look like slices of wall with various paintings, signs, windows, and knick-knacks tacked onto them. Where do all those images inside of images come from?

KMT

Yes, you’re right, I think these are related. The works containing multiple images, pictures and objects operate like a flat file where I can put things I’ve been looking at and doodling and reproducing and reworking.

I also like to think about interior spaces as venues for the drama of the accumulation of visual culture, personal culture. You keep something around because you love it and you’re glad it exists exactly as it does and you display it so it can remind you to be a better, more expansive person, more fluid in your expressions of living, more varied in your comforts. These knick-knacks and signs and images also keep us company. We give them sentience and they give us sentience too. These works we’re talking about are depictions of that drama.

The research and accumulation of my own visual galaxy happens everywhere at all times, as folks close to me can tell you. Storefronts, trash piles, digital collection archives, libraries, Google rabbit holes, and many many books. One can only gather if indeed they are looking. I am obsessively, hungrily looking—a crazed animal.

LMF

When I was very little, I went to a one room schoolhouse in the country run by two nuns. Throughout the space there were white shelves with feathers, shells, rocks, nests, and other things that I suppose the nuns had collected over the years. It was part of our education to look at those objects, examine them, and they became quite special. We were quite young, but the nuns had us clean the school.

I loved taking all those objects down, rearranging them in my own configurations on the carpet, dusting the shelf back to a clean, fresh white, and replacing them. Anyway, it reminds me of what you said about knick-knacks, and how you arrange those images inside of images. What are some objects you always keep?

KMT

Wow, what an enchanting memory, Lauren!

I don’t have any such enduring legacies of object arrangement, at least not so beautiful, but I think often of the delight of setting things out and doing it with sensitivity and precise tenderness. It does feel linked to the eyes of childhood and the domain of wonder. Lately I’ve been including more and more the verb “putting” in the vocabulary of my studio practice. To put things, you know, on things, next to things, to adjust the angles of things, to make relationships between objects and images and colors and textures, to make lovely negative space, and to form constellations of meaning.

I’ve accumulated many objects and printed material, which live with me in various ways. Some are sacred and stay in my house and some I’ve introduced into my

studio realm. I have a bunch of pinecones from all over the world. I have expressive sticks and rocks. I have tool-like things with oblique histories and purposes.

Enigmatic tchotchkes, of course. I have many things my friends have made. I put these things in places with great care and love. I’ve just discovered these photographs by the Swiss artist Rudy Burckhardt in which he’s sort of staging and restaging objects in his Manhattan apartment in the 1950s. I find them so special.

Something I’ve done in my studio for years and have also done in exhibitions is use shelves to display and hold these objects as well as things I’ve made. I became interested in making the shelves myself and developing that as a language of its own. The shelves sometimes reject objects; they don’t want to hold things; they would prefer to just be themselves objects. I like to have things I’ve made live with things made industrially or out of depths of anonymity. I am very keen on that collapsing of authorship.

LMF

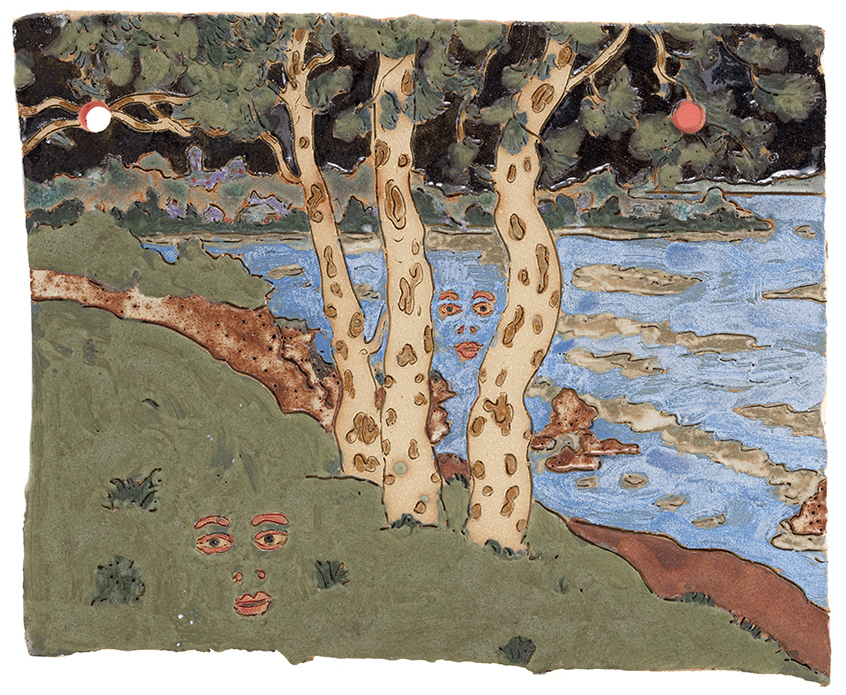

After a trip to Inverness, California, you described the “dramatic cliffs over rocky ocean seemingly lit blue from the bottom led to bulging flowery hills disappearing into each other in subtle variations of green dissected by narrow roads which farther inland pass through trees so tall the temperature changes drastically and a light reaching the floor comes in arrows that are hilariously beautiful. The whole thing had me laughing with amazement.” There’s so much humor and there’s so much nature in your work that I found this particularly poignant. Can you tell me more about how you relate to humor? To nature?

KMT

Beauty and humor seem to me similar expressions of the sublime exasperation of being alive. When the information of a sensory experience exceeds our capacity to generalize and classify, beauty forms and we are subjected to it. Then there’s nothing left to do but witness. I think that’s similar to how humor works. It occurs when the information of a moment is too effervescent. At the point when beauty and humor emerge, we feel relief, I think, that our logic and and computations are, at last, not necessary. Finally and suddenly we are not suffocating under the burdensome mechanics of measuring and narrating existence to ourselves. And then we laugh and smile because what else can we do among the riotously lovely Bishop Pine trees in the purple light of dusk in Inverness, California? The golden pinecones of a Bishop Pine look like elongated coins, the needles flay out like illustrations of divinity around a halo, there’s an unlikely lavender light contouring the rusty upright trunk, and it smells like the ocean is in the sky. We feel the presence of sentience beyond ourselves and a logic that we have not constructed and can only behold. Exhilaration, hysteria, laughter at the margins of the mind.

"Beauty and humor seem to me similar expressions of the sublime exasperation of being alive. When the information of a sensory experience exceeds our capacity to generalize and classify, beauty forms and we are subjected to it."

LMF

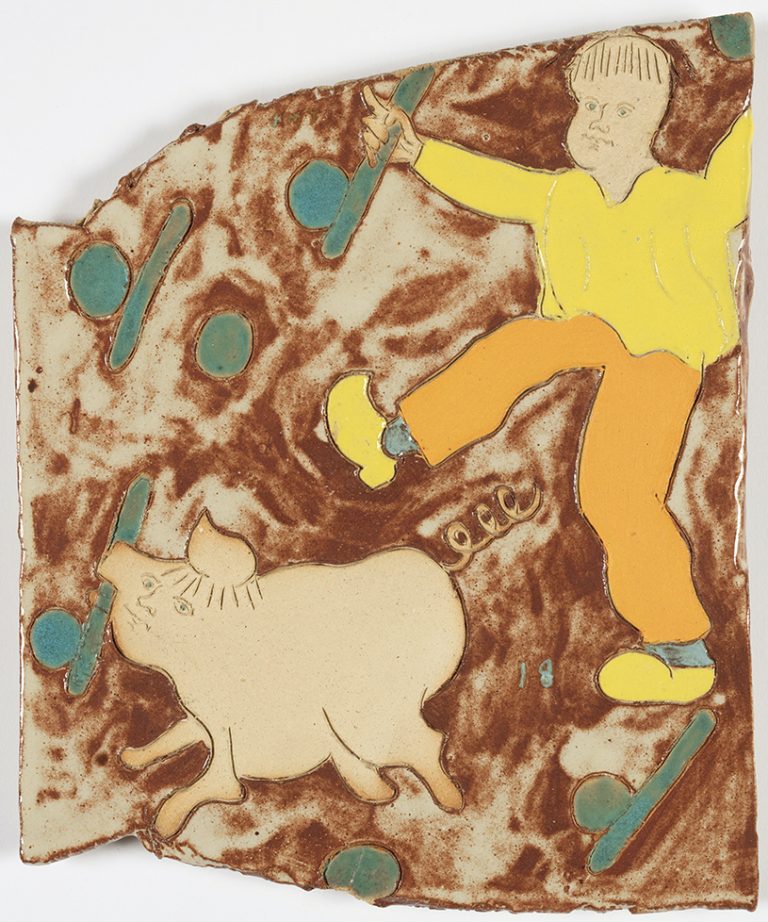

There’s also a definite sense of humor in some of your pictures: a pig with a man’s face, a cat with an impossibly long tail, a hand with the pinky out, a foot with too many toes, and, of course, the eternally lumpy artist’s beret. There it seems like humor is coming from a different, more wonky impulse.

KMT

Bing bong. You know?

I consider humor a necessary part of being alive. When I was in high school I was reading a Kurt Vonnegut book in which he writes something to the effect of “There is no remedy for [life or something], unless laughter can be said to remedy anything.” That really struck me as profound and liberating. When I started making visual art again after years of excruciating experimental writing, humor was pretty much the primary function of the work, although it was crucial that the humor be a conductor for other, perhaps heavier emotions. I wanted sadness and bitterness in my images, but I also wanted to lend some objective distance from pain, which humor does exceptionally well. The discomfort of hurtling through space on a green and blue sphere called Earth with only a human mind and body to measure unfathomable things, for example, is a little easier to accept and befriend in the company of humor. I think humor can be linked very intimately with the sublime. Of course we must monitor humor so that it does not undermine sincerity and romance, but I believe in a cohabitation of all these things. Humor is an antidote, as Kurt Vonnegut said to me as a teenager, but it’s also very adaptable and generous.

LMF

You also told me that you don’t believe you have a particular process or medium, that you work until you shed a skin completely and find your way into something new. How did you come upon your current mode of working? Is your skin still on tight, or will it shed soon?

KMT

I absolutely don’t have a particular medium. A medium is just a lexicon. It can be exciting to see what one can express with a given material language. Inevitably, a language has its limitations. It’s hard to tell a story of fleeting romance, for example, using only math, just as it would be bizarre to explain that one hundred and forty-six plus two is one hundred-and-forty-eight in a novel. So I explore what can be explored within the vehicle of a given medium. Ceramics have been a vast frontier of exploration, for a few reasons. I’ve been able to draw in the scale and line weight that I prefer, which means I have dexterity and fluency. I like objects that are modest in scale, not much bigger than a piece of paper. There’s a great quote of a quote I heard in a recording of Bernadette Mayer introducing Joe Brainard at a reading at St. Marks Place in the early 70s: “John Ashbery said of Joe Brainard’s modesty,” says Bernadette Mayer, “that his modesty is the modesty of the gods.” I think gods live in modest forms and scales in relation to the human body, not absurd monuments to the endless ideologies humans construct. Anyway, the surfaces and textures and colors and physicality possible with glazing adds something very powerful to my imagery. The things I draw can have bodies and live with us in physical reality. Beyond that, I tend to say that I am interested in images and objects, and not necessarily “Art” images and objects, you know? So the things I make have to exist in space with the same rubrics of meaning as regular, non-art objects.

LMF

What’s the difference between images and objects and “Art” images and objects?

KMT

I try not to distinguish between them.

LMF

In an interview you did with the Austin Chronicle, you said that monoprint “is essentially just like drawing, only backwards and blind and with very little control.” I wonder: does a roundabout path to drawing have something to do with your work in ceramics?

KMT

Roundabout, yes, but not too process-obsessed. I think of printmaking which, for example, can be mind-numbingly tedious, laborious, and far too entrenched in set-up and clean-up. There feels to me too in printmaking that there is a bit of animosity towards chance and mistakes. The method of my monotypes was hardly in the genealogy of things like lithography or intaglio or even mono-printing with oils and a press. There was tremendous immediacy with that process, even though the act of mark-making became uncannily detached from the act of looking at what mark you are making.

Much happens behind curtains in ceramics too, with kilns being the site of dramatic transformation. And there are certainly many steps involved: The process can begin with making the clay itself. Then it is rolled into flat forms which are cut and divided into various shapes and sizes. While still wet, I draw into the slabs with different tools. Then they sit and dry. I bisque fire once they are bone-dry and no longer cool to the touch. Then comes the glazing. I make almost all the glazes

I paint with apart from a few reliable commercial glazes. I’ve accumulated recipes I like and developed some new ones based on a very limited understanding of the chemistry at work. I paint with cheap brushes except a few fancy bright ones. One corner of my studio is lined with teetering tubs of chemicals and minerals mixed with gums and water and blended with a hand mixer. After applying the glaze, one prays and loads the kiln for the final firing. I generally fire to cone 6 at this stage, which peaks at 2,232 degrees Fahrenheit. Opening the kiln at the end of the firing is a horrifying, thrilling and humbling experience every time. The process of making ceramics is indeed roundabout and so volatile. I do appreciate that one can never really anticipate the outcome of any given glaze on any given day. I also revere the constant threat of annihilation: things break!

LMF

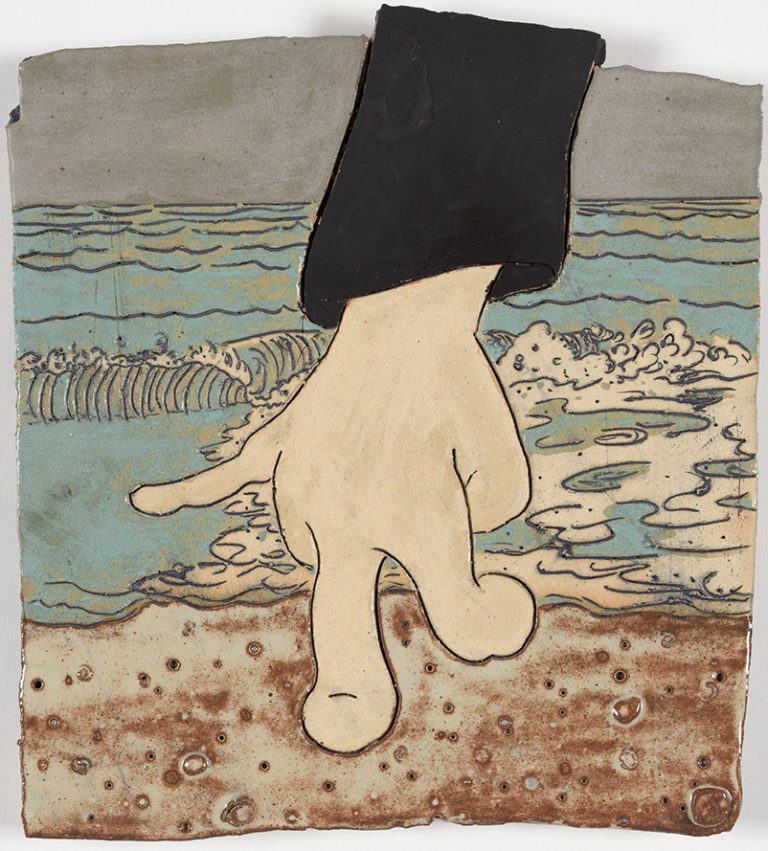

Speaking of what happens behind the curtain, I notice that you frequently depict the act of painting and drawing in your recent work, which feels like a wink. There are also many reflections and repetitions—in mirrors, on the surface of water, on canvases—that seem to refer to a conversation you’re having with yourself. Where do these themes come from, and what brings you back to them?

KMT

I think maybe all the mirrors and reflexivity are just an attempt at some mindfulness: “I am doing this, this is what I am doing” kind of thing. The creator and viewer and the object itself all participate in this self-awareness for a moment, which puts us sweetly in touch with the uncanniness of being ourselves and not being another person or an object for that matter.

LMF

I also want to know about your butterflies!

KMT

The Butterfly Paintings started just before I spent a month in Mexico City;

I also made a lot of them while there. I feel they gave me a system in which to think about color. I came to this abstracted formation of circles and a rectangle to signify the butterfly and then I could just play with color combinations and experiment with various pigments and textiles. I fell into that mode of making after a long stretch of making many ceramic paintings, which demand an editorializing and narration that I don’t always want to engage with. I move between mediums quite freely and often. I love the butterflies. They feel good to make and pretty good to look at.

LMF

A few years ago, you told me you wanted to go to Spain, Italy, and Mexico City; I think you’ve seen them all by now. How does traveling affect your work versus staying put? Do you make things while away from home?

KMT

I always like the idea of making work away from the home studio, but it happens very rarely. I was in Mexico City for about a month and was able to make a suite of paintings on various materials with various pigments. I worked super quick and loose. Good to change up the speed. Good to use your eyes and body differently. But traveling is really more about retrieving data. I’m just looking at entrails of visual culture and recording with a camera and notebook. I take tons of pictures. I generally feel like I’m performing research when I travel. Which is exciting.

LMF

On the other hand, it seems like when you are home, you’re firmly rooted. You’ve got your dog, your library, your ceramic practice. Is that accurate? Are you very tied to the place you live?

KMT

Yes, and definitely no. Home is a strange word. I grew up in North Carolina, but my parents were both from Philadelphia, so I wasn’t really really Southern. I don’t have that kind of family/geographical lineage, which I think has meant that I don’t locate my home very firmly. North Carolina is not my home really. My parents don’t live there anymore. I love where I live now but I won’t be in Iowa City forever. Texas never resonated with me as a home place. New York is essentially Mars, so that wasn’t ever a sustainable option. Home is basically impossible for me, but I like to exist with houses and things and the person and animals I love. I’ll be in Iowa for another while longer I’d say, but who knows. I have loved living with snow. Folks like to complain about it, but I remain enchanted still. It has such transformative powers and, most fundamentally, it is just so lovely. The light changes drastically, surfaces and forms take new contours and do this dance with negative space which is endlessly mesmerizing. Things are brighter as well because the white reflects and diffuses the sunlight. So much of the light is bouncing up from ground-level, which is a bit unreal.

LMF

You arrived in Austin right around the time that it was becoming “cool,” and you witnessed the city step awkwardly into that role during your time there. Then in 2017 you moved to Iowa, a more peripheral place. What’s it been like to make work in a Midwestern, academic context?

KMT

Austin really nourished me in a time of waywardness. It has a certain knack for making disillusioned people feel like they can tread water a little longer. And quite literally with Barton Springs I felt I was healing and satiating the wound that is time always racing away. I managed to become very productive there.

Iowa City is a perfect place. I feel so lucky to have landed here. It’s got such a good feeling to it. It’s got enough stuff to do and eat, and one can walk or bike everywhere easily. There are rivers and creeks and woods. My life has been extremely conducive to studio productivity and research. There are incredible resources and people at the university. I came here in part because of the Writer’s Workshop and the Center for the Book, which go a long way in establishing the culture of this exceptional place. Academia is of course a ridiculous bubble reality, but as one surveys the various contexts to exist within, it stands apart as a marvelous way to balance work with life.

LMF

Lastly, I realized that I don’t know much about your past, or how you became an artist. How did you first discover art, and how did you decide that visual art was your path? Does where you’re from factor into what you make?

KMT

I lived a few places early in life before my family settled in North Carolina when I was in third grade. Then I was in New York and Texas mostly with brief stints in the Bay Area. I do feel the places I’ve lived have impacted my imagery and objects, my material and subject choices, and even studio temperament and spirit or making. Places I’ve only visited factor in as well and places I’ve never visited too. Places, like everything else, are subjected to the narratives of meaning humans use to define reality. A place is a very wobbly measurement of space and what happens there. When I think in this way I recall a story I’ve always wanted to write about the time nine o’ clock in the morning traveling around the globe. Moving over land and the water, hovering over the smell of coffee, drifting over waves in the sea, shrinking in the presence of mountains, becoming a sharp, hot bead of sweat on the neck of a child who’s late to school somewhere, and so on. When the idea of place enters my work I feel it has a sense of fictionality and acute subjectivity and relates more to how a place might inhabit our memories than having much to do with “real” places

I don’t know how I first came to art. Drawing was certainly the first germ, as is often the case. I had sketchbooks for periods in my life, but neither drawing nor art were of sustained, uninterrupted interest until I was in my twenties. I never felt I found it or decided anything about it, even now. I love drawing and creating objects for the space it provides me to think in different ways, to find new things and to witness existence and meaning-making with some objective distance. Art is something else. It’s not the same thing as making things. Art is after that.