INCOMING ARTISTS: George Rouy

The London-based figurative painter putting sincerity back into art

Text by Kathryn O’Regan

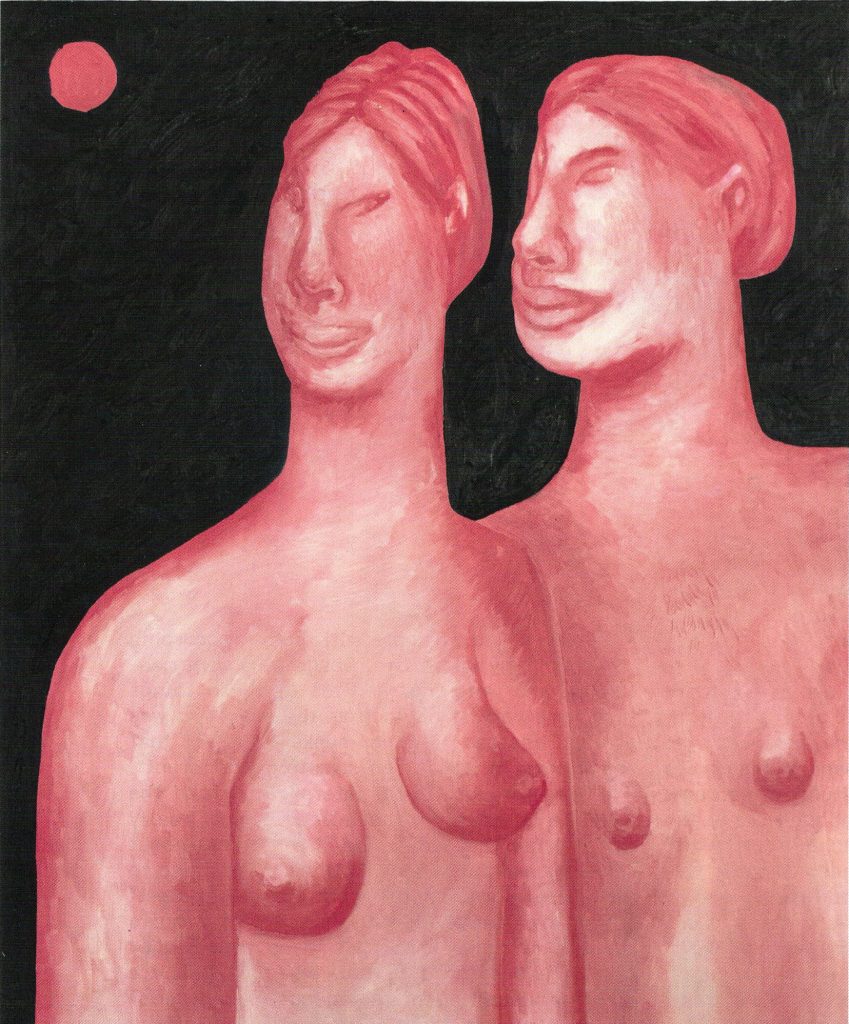

Sincerity comes up a lot when South London-based artist, George Rouy, speaks about his art. Working mostly in figurative painting, the 24-year-old is interested in making work that has “a human aspect, a kind of emotion, a softness.” Knowing this changes the way you look at Rouy’s paintings, tubular figures that bend and flex like bubblegum across his largescale canvases. In their exaggerated curves, stretchy pink-toned figures could resemble the generous, rounded shapes of, say, Picasso’s neoclassical period, but really, Rouy is much more concerned about his art being more like a diary entry than an intellectual concept.

Rouy, originally from Kent, studied painting at Camberwell College of Arts in London, and it was only towards the end of his degree that he started to feel “comfortable” with the medium. While at art college, he didn’t think that painting, particularly figurative painting, was appreciated. “To be a figurative painter it was like ‘What are you doing?’. It had no relevance.” But when he graduated in 2015, Rouy started to see the medium in a new light. “It became really clear to me that figurative painting has a huge relevance at the moment in terms of identity,” he explains. He discovered that this style of painting elicited a strong reaction from people because nowadays, there is “such an awareness of how you’ re perceived and who you are and what you represent.”

While he’s definitely interested in how other people respond to his work, ultimately the purpose of his painting lies in a personal – albeit ambiguous – representation of his relationships with other people and to himself. “I think at the moment I can only refer to myself and 11y own feelings about certain things,” reveals Rouy. “What I found by doing that though is that someone else can relate – it has an impact that Nay. I try not to push it too much. I would really like to keep it open and for the paintings and shows I do to have their own presence.”

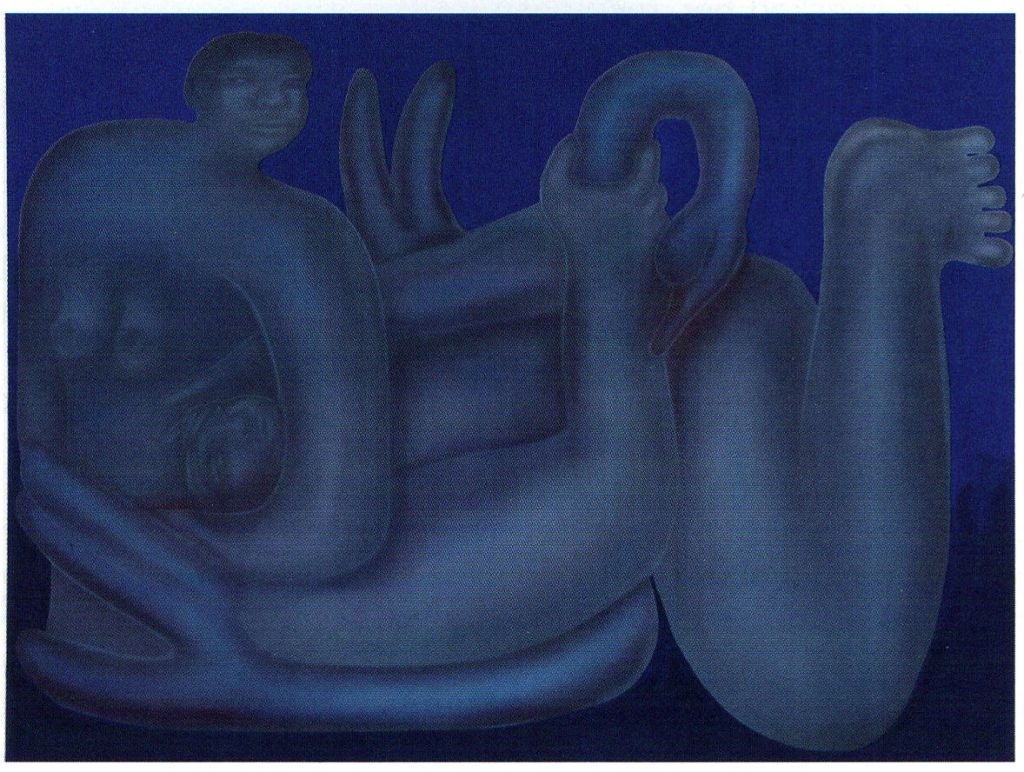

And what a presence that is. His paintings skulk with murkiness and motion, far away “rom order and predictability. Paintings like Exposed in Hiding (2018) have a cartoonish and fantasy aspect to them. At his 2017 exhibition, In Dirty Water, at J Hammond Projects in London, Rouy was inspired by the primordial energy of dancing (and fighting). “I was looking at dancing as a human expression, quite a ure, primal way of seducing and marking your presence. There’s an ego thing to it, especially going to clubs and seeing how people react.”

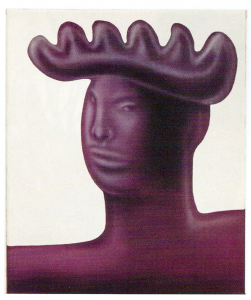

While some of his paintings are full of this verve, others have a symbolic weightiness that harks back to medieval and Renaissance art. The symbol of the swan features heavily throughout his work as a subversion of the creature’s mythological status. In the lushly painted, Black Swan (2018), a majestic indigo bird nests, his elegant neck awkwardly curling, his beak reaching skywards. For Rouy, the image is rooted in a personal representation of a “failed masculinity”, symbolising “the warped world we operate in as males”, and somehow “a swan with a broken, bent neck shows that.” Meanwhile, in another work, the purply, raspberry-toned, Horse and Apple (2018), Rouy considers the horse to represent “an idea of longing, a kind of lust, a desire”.

Rouy also cites Chris Ofili’s, No Woman, No Cry (1998), as a key inspiration for this work and a major reason for his return to figurative painting after art college. “It was one of the first paintings that I kind of looked at in the gallery and really had an emotional response to. It shifted my whole perception of what art should be in terms of the emotional and human level it had,” remembers the artist. “There’s a certain kind of pureness and sincerity to it.” It’s important to Rouy to make work that creates a similar stir.

At the moment, Rouy is trying to “open his practice up” and experiment with his technique. In January, he completed a four-week residency in Merida, Mexico, working alongside his friend, the artist, Jesse Pollock, on a series of coated steel pots, in preparation for an exhibition in the autumn at New Art Centre in Salisbury. He’s also been working on a series of smaller, more intimate paintings that emphasise the pared-back, symbolic tendency of his practice, and is preparing for a solo exhibition at Copenhagen’s V1 Gallery in the summer. When asked about why he thinks people have such a strong connection to his work, he responds with candour: “You know what? I’ve no idea. I don’t really care too much. I think there’s an honesty and sincerity – I’m doing it for me. I’m doing it because I really love it. If it resonates with people to a certain extent, I try and maintain that sense of sincerity.”