From Marina Abramović to Carlos Martiel, a Tradition of Self-Harm in Performance Art

Nearly five decades since Chris Burden and Marina Abramović began their explorations, an emerging crop of artists are re-envisioning artistic self-harm in both methodology and intent.

| April 4, 2019

Crucifixion and flagellation, bodies pierced with arrows and set alight on pyres, tongues torn out, and breasts sliced off — Western art history is rife with images of suffering. After centuries of depicting pain (often as a means to induce piety), artists in the 1970s on both sides of the Atlantic began exploring pain itself as a creative act. In his 1971 performance “Shoot,” American artist Chris Burden had his assistant nail him in the shoulder with a .22 gauge rifle. Two years later he followed up with “Trans-Fixed,” where he had his hands affixed Christ-style to the hood of a Volkswagen bug. Marina Abramović’s Rhythmseries saw her slashed with knives, pierced with thorns, and, in the climactic moment that concluded the project, allowed a viewer to hold a loaded gun to her head.

Despite their dramatic appearance, these tactics can be seen as a natural progression in performance art’s quest to employ the body as material. Burden, Abramović, and their progeny treat the human frame like a canvas — an object to be nailed, sewn, slashed, and stapled. As Tracy Fahey points out in her essay “A Taste for the Transgressive,” transforming the body into an art object blurs the line between artist and artwork. Consider, for instance, the works of Orlan, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, and Nina Arsenault, who reshape themselves through plastic surgery as a creative statement.

Creative self-harm can of course be a shock tactic, though the intentions behind it vary. Russian artist Petr Pavlensky nailed his scrotum to the cobblestones in Red Square hoping to highlight his government’s oppressive tactics and the wider culture’s political apathy. In contrast, American artist Adrian Parsons performed a self-circumcision with a dull knife at a DC gallery with no political or critical framework, apparently with the sole aim of drawing attention to himself.

Artists can also risk their message being confused. Ron Athey’s 1994 work Four Scenes in a Harsh Life (which saw him spell out words using blood-soaked paper towels) aimed to address issues around HIV, body image, and homophobia. Instead, it fueled a heated congressional debate about arts funding, ultimately leading to an NEA budget cut (ironic, given Athey’s piece only received $150 indirectly of NEA money).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, artists working with self-harm risk being labelled as damaged people working through trauma publicly in lieu of therapy, or shock-jocks incapable of creating aesthetic experiences other than horror and disgust. They are sometimes treated like moody teenagers with a sudden penchant for black clothing — just let them be and eventually they’ll grow out of it.

Nearly five decades since Burden and Abramović began their explorations, an emerging crop of artists are re-envisioning artistic self-harm in both methodology and intent. Less violent and horrifying, more poignant and intimate, their works aim to communicate similarly complex messages to viewers, but through subtlety rather than shock. Their work, it seems to me, may have more in common with the history of religious painting than with their more provocative predecessors. Rather than taking the body to its limits, these artists instead explore it as a site of possibility, where pain is not a goal but a pathway to personal and spiritual change.

For Cuban artist Carlos Martiel, shedding blood is, in a sense, incidental to the work — less a part of the performance and more like a trip to the art store. Blood isn’t usually produced during the event. It’s more often collected in advance, usually by a nurse who withdraws the required amount. 2018’s Black Lament sees him stand motionless for hours in a pool of his blood. In 2019’s High Risk, threads soaked in blood from an HIV negative person on PreP (a treatment that prevents transmission) form a cross around his body. The religious references become more explicit in 2017’s “Peso muerto” (Dead Weight) (where he’s restrained by a wooden cross) and 2012’s “Yerto” (where he lies motionless shrouded in a white sheet, hinting at Jesus awaiting resurrection).

“If an artist is trying to shock people, it’s very obvious,” Martiel said to me. “When people see my work, I think they can see I use blood in an intelligent way. I want to say things about my body, about the history of the black body, and about immigrant suffering. It’s a way for me to express those things and to explain something about the society we live in. I think anyone who knows about art can see that in my work.”

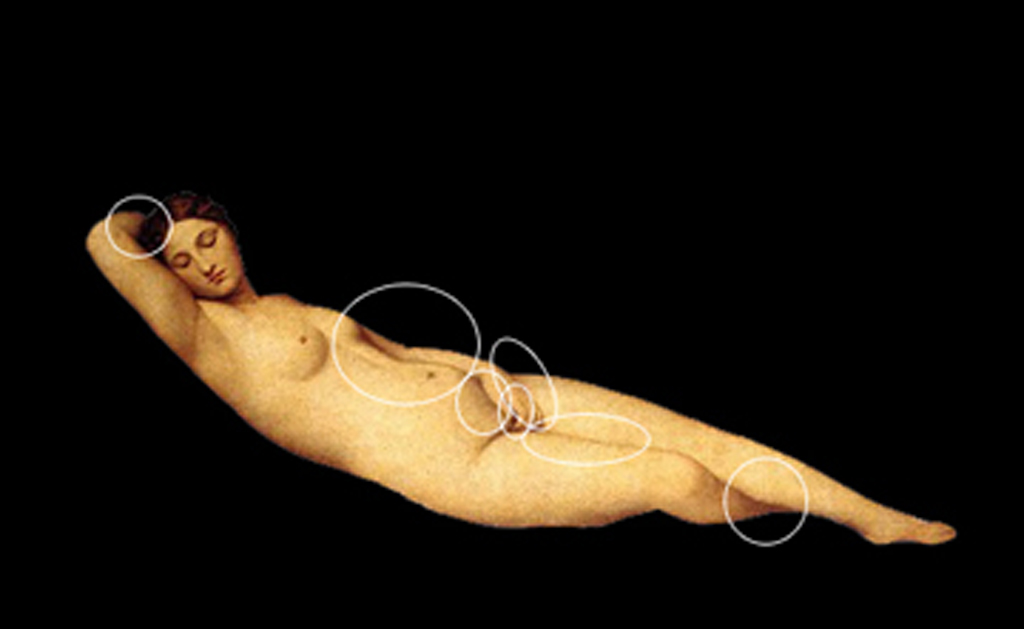

Montreal-based artist Michelle Lacombe works more generally with images from Western art history, in particular canonical images of female figures. She considers her works “interventions into the body” rather than acts of self-harm. In 2010’s “The Venus Landscape,” she had strategic lines tattooed on her body which, when properly aligned, place her in the same pose as Georgione’s “Sleeping Venus.” Her 2012 work “Portrait of a Self Memorial and an Anonymous Aesthetic Beheading,” saw her seated on a plinth with a scar along her upper torso referencing the measurements of a classical sculptural bust.

“I work a lot with images and archetypes from Western art history and inscribing my body into this history comes with the baggage of social and cultural readings,” she said over Skype from her Montreal home. “In a way, I’m trying to reframe my relationship with those histories. I don’t know if it’s transgressing or reappropriating or just coming to terms with them. But it becomes a form of solidarity with the figures I’m questioning.”

Canadian-born, London-based artist Adriana Disman frequently draws blood during performances. But it’s usually done in very understated ways. In 2017’s “Swallow” she stands face to the wall, slowly turning her head back and forth in a “no” gesture until the tip of her nose begins to bleed. In “still alive/game over,” from the same year, tiny cuts on the back of her legs produce trickles of blood suggesting the seams of silk stockings.

Disman isn’t so concerned with people misinterpreting her work as an individual artist. But she does worry about how the media and, by extension, the wider public might interpret these forms of performance and the effects this has.

“I’m concerned by the instrumentalizing of performance art in the media to incite moral panic,” she explained to me. “I’m concerned with the making-ridiculous of performance artists, a step away from the making-crazy. By naming someone crazy, you can delegitimize everything they say and do. It almost always means treating them unequally, which is part of how larger systems of power organize bodies.”

Along with Lacombe, Disman, and Martiel, there are other artists working with similar practices: Marina Barsy Janer’s work with bloodlines (tattoos without ink) and acupuncture, Boryana Rossa and Oleg Mavromatti’s blood stencils, and Alice Vogler’s insulin injections. And while the works of this new crop of artists aren’t widely discussed or noticed, they mark a clear creative progression from the work of their more flamboyant predecessors in the 1970s.

Adriana Disman is performing “Questions without answers must be asked very slowly” at the Hearsay Festival (Limerick, Ireland) on April 4–7.

Carlos Martiel is performing “La sangre de Caín” as part of the Dedelmu project at the 13th Havana Biennial on April 14.