Art day in L.A.: A walker’s guide to gallery hopping along Highland Avenue

By Sharon Mizota, Sept. 30, 2019

Francisco Rodriguez, Rebecca Shippee and Jon Key at Steve Turner

The three shows at Steve Turner restored my faith in the enterprise. Francisco Rodriguez’s paintings feel as sun-bleached as the L.A. sidewalk, depicting desolate yet claustrophobic landscapes populated by lone men or large, black dogs. “In the Garden” reminded me of the man splayed outside. In it, we see only a pair of legs, lying in a pale beige field studded with red flowers. A black crow sits ominously near the figure’s feet, improbably smoking a cigarette. Along the high horizon line is an oily black line of trees, and behind that, a high chain-link fence against a pale red sky. Something bad has happened here.

“Corner,” is even more oppressive. The horizon line is the top of a tall, solid fence, hemming in a small, black figure hunkering down in the corner. Above the fence we see only the tops of those threatening black trees as they seep like ink stains across a pink sky.

The title of the show is “Midday Demon,” and even though Londoner Rodriguez isn’t from L.A., his work captures the oppressive, carceral atmosphere that sometimes descends on the hottest, most hopeless days.

Rebecca Shippee’s portraits in the next room are more reassuring. They depict people who have altered their appearance, either through surgery or wardrobe, to reflect their gender or sexual identities. “Noah,” despite the masculine-sounding title, depicts a pale-skinned woman lying nude on a sofa. The composition is reminiscent of the frank figures of British painter Lucian Freud, although without his fleshy specificity.

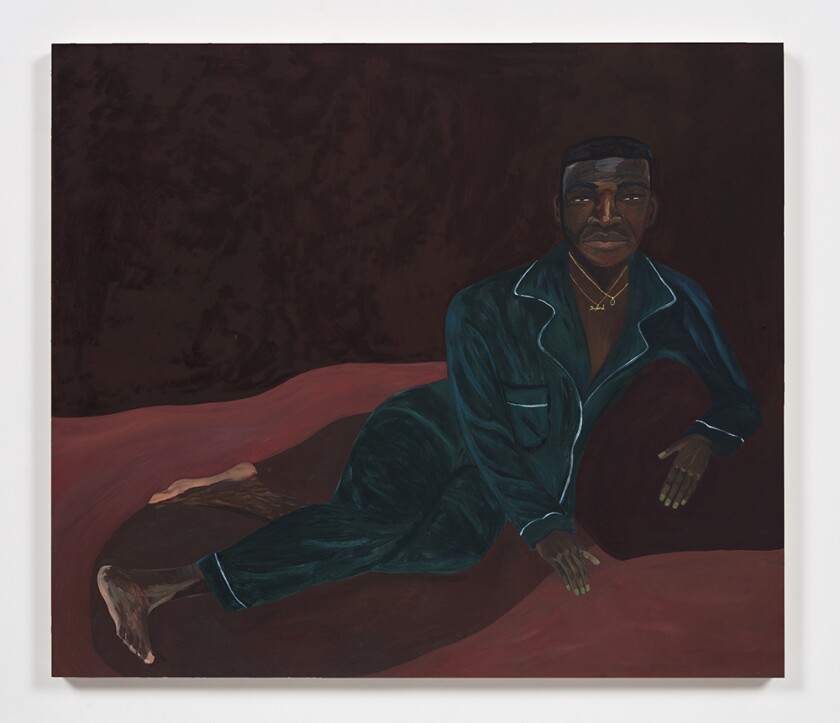

On the opposite wall is “Jarvis,” also a reclining portrait, but this time the subject is a black man, clad in deep-green pajamas and sporting a necklace that reads “Boyland.” By depicting these two very different subjects in the same, classic, “reclining nude” pose, Shippee places both of them in an art historical lineage that has traditionally signaled beauty and desirability, but has also traditionally been reserved for white, cisgender women.

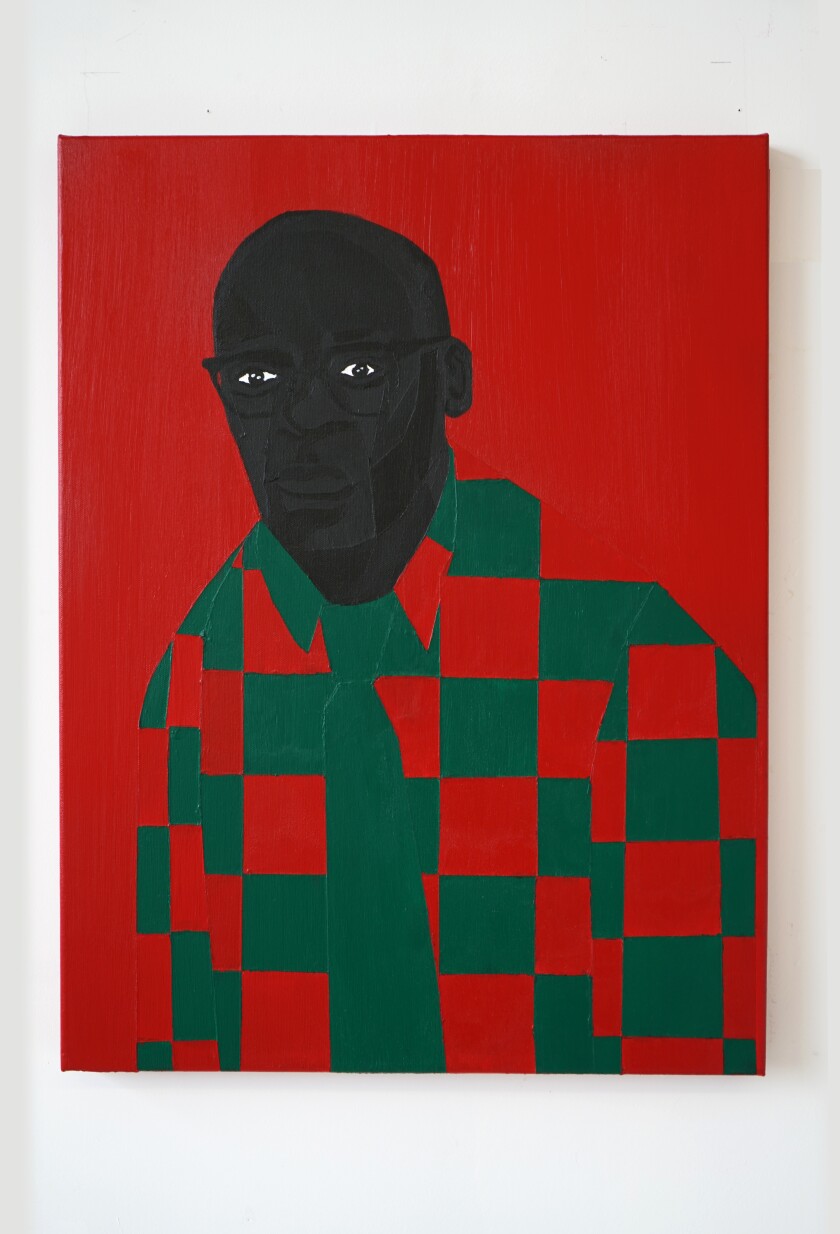

In the third gallery, self-portraits by Jon Key skew the art historical canon in a different way. His self-portraits are executed in solid blocks of just four colors with symbolic significance: green for the South (Key grew up in Alabama), black for his African American identity, violet for queerness and red for family. The idea is a bit simplistic, but the modestly sized paintings possess a graphic appeal with their reductive palette and shapes. They evoke geometric abstraction, but also the patterning of African fabrics, and of course, Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African flag, with its red, black, and green stripes.

I almost walked right into a two-sided panel hanging in the center of the gallery. Spinning slowly, it depicts portraits of Key’s father and grandfather. Tellingly, there is no purple in these images, a subtle recognition of family tensions around Key’s sexuality. The paintings hang in the center of the space like a question mark.