ArtSeen

Jon Key: Violet: Mythologies and Other Truths

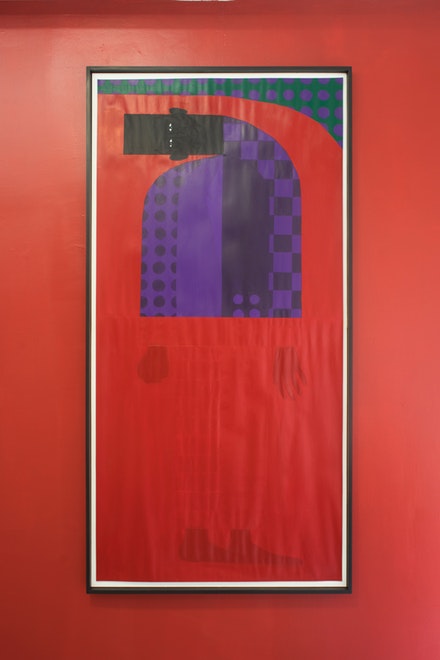

In a lush new series of works at Rubber Factory, Bushwick-based artist Jon Key layers personal realities, myths, and acrylic paint in the spaces between body and landscape. His scenes are inspired by the greenery of Henri Rousseau and the Hudson River School, yet assert “other truths” about land and its inhabitants. Incorporating his Alabama roots, Key subverts Rousseau’s exotisizing fantasies and the Romantic promotions of the arrogant Manifest Destiny by artists like Thomas Cole and Albert Bierstadt. His landscapes are inhabited by a reoccurring figure in a dapper violet suit who cranes his neck past anatomical possibility and looks back at you with eyes vertical and upside down. The nimble figures—black and queered—refuse rigid masculinity. They are delicately rendered with one clenched fist, their power and vulnerabilities underscored by Key’s brushstrokes and methodical layers of acrylic on heavy paper rather than canvas. Flatness and texture become visible strategies of agency as Key fully controls the surface of his composition. Embedded throughout are polka dots that peek out as fruits between leaves and checkerboard patterning that shapes mountains. Full of curves and impossibilities, Key’s surreal dreamscape is embraced by the immersive installation at Rubber Factory, where his colors and patterns extend outward—the red bleeds, the green of foliage outgrows frames, the purple polkas infest the wallpaper and stick on the outside glass of the gallery.

While sharing some of Rousseau’s sense of fantasy, Key’s semi-autobiographical compositions are grounded in the familial. The repeated patterns, for example, are not only endlessly effective graphically, they also relate to the personal: “Polka Dot” was his grandmother’s nickname and his father wore checkerboard plaid as a construction worker. This and other intimacies contrast the work of Rousseau, who likely did not travel to the “exotic” locations he portrayed. Often basing his paintings on images from books and animals from the Paris zoo, his Eurocentric vision reflects his distance, disconnection, and white gaze. What is memorable about Key’s practice is that it is shaped as much by art history and graphic design as much as it is by the queer, black, familial realities he has a personal stake in depicting.

Key’s formal cohesiveness reflects his thematic unity. The paintings’ shared palette of black, green, red, and purple acts like a filter: a veil for the way one sees the world, for the way one constructs the landscapes around them and, perhaps, also a reflection of DuBoisian double consciousness—a realization of how dominant culture sees and yet, never-sees, your marginalized body. Like other black queer contemporary artists, Key reclaims the presence of that body. Key’s work reminds me of Mickalene Thomas, whose shining paintings, videos, and installations unapologetically reverse the gaze and queer the legacy of the female muse. I also think of the life-size canvases of Kehinde Wiley, whose often-queer black figures are made regal with motifs historically applied to white bodies.

In Violet, Key’s figures may be solitary but his sense of community is clear. He—along with artists Son Kit, Sharina Gordon, Leandro Zaneti, and Jarrett Key—is a co-founder of the collective Codify Art, which aims to amplify the multidisciplinary practices and voices of people of color, and of the group Artists Against Police Violence, “an online space featuring graphics and artwork to be used for communities against police murders of Black people.” Collaborative efforts like these remain essential for underrepresented artists navigating an art world that remains tightly tied to systems of power.