Monroe Denton, Art New England, January 24, 2014

PART 1

Deborah Grant has always taken as her subject nothing less than the story of humanity. It’s a project as heroic as it is foolhardy. Yet the entire range of Western culture is her arena—from the Garden of Eden to a contemporary world of signs and logos, where conflict is reduced to a sound-bite in representation, leaving the original war to simmer beneath the surface.

Deborah Grant entered the gallery and exhibition scene in 2000, although for more than five years she had been notable in her absence on the East Coast, showing primarily with Steve Turner in Los Angeles. This season marks a major re-entry to the gallery world with a large, fascinating installation at the Drawing Center opening late January. She is also included in a tightly curated group show of artists whose post-modernism is strongly rooted in folk tradition. This takes place at the Studio Museum of Harlem, opening in March.

The artist’s mature work has been characterized by an approach that, perhaps in light of the idea of branding, Grant has dubbed “Random Select.” It’s a visual conceit inspired by rap sampling. Any image is eligible to be thrown into the image hopper and then sampled, either in an individual work or incorporated as a tessera into the larger mosaic of a wall-sized project. Just as samples can be either purely musical or verbal, so such “logos” can be either visual, like trademarks; or verbal, individual letters or phrases from historical or mythological texts. In this way, Grant is linked to Paul Chan, whose video images sample cultural icons of a similarly broad range. Grant’s works emerged a few years prior to Chan and have remained grounded in a concrete physicality that perhaps has obscured their own radicalism.

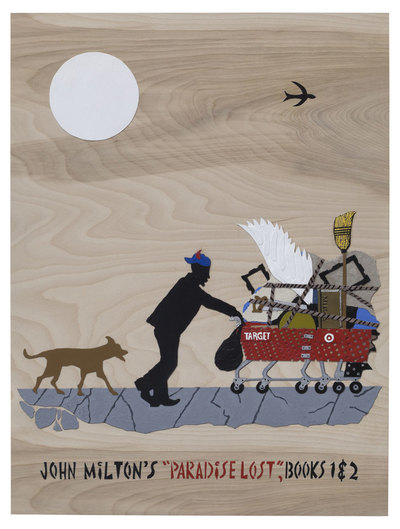

John Milton’s Paradise Lost Books 1&2, 2013. Oil, acrylic, enamel, paper and linen on birch panel, 24 x 18 x 1 1/2 inches

Images from the Judeo-Christian tradition always have been foundational to this artist’s methodology. Grant, who was born in Toronto, grew up in New York’s Coney Island area and attended parochial school. Her childhood was spent in part as a little sister to a graffitist brother. She was raised in the Roman Catholic tradition in an exceptionally stimulating neighborhood, rapidly transitioning from Orthodox Jewish majority to African American and Afro-Caribbean American. As a young girl a neighborhood rabbi introduced her to the majesty of the Torah and some of the mysteries of Orthodoxy. She was thus pulled between the oldest Western monotheist traditions. Later, political awareness and introduction to subsequent immigrants, often from the Middle East, brought Islam into her figurative bank.

Studying for her MFA at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, Grant became part of a breakthrough generation of African American artists including Trenton Doyle Hancock and William Villalonga. Of greater importance, perhaps, was her exposure to art history, which provided image sources within the African American art tradition and wider modernist history.

Her work would be characterized by exhibitions focusing on individual artists subjected to the Random Select process (e.g. John Michel Basquiat, graffiti culture, and commercial signs in How to Get Blood out of Bedsheets, 2007; the Arab-Israeli conflict in A Gin Cure—its title an anagram of Guernica, 2006, 2007; William Traylor; Thornton Wilder’s civilization-spanning Apocalyptic vaudeville Skin of Our Teeth in By the Skin of Our Teeth, 2007; William H. Johnson, the Jazz Age, and Civil Rights history in The Provenance and Crowning of King William, 2012.) In each case, themes from one series find expression in another. The Random Select process is inclusive and expansive rather than restrictive.

A common theme in many of Grant’s projects has been the idea of a break in European ideas of rationality—at its extreme, insanity. This might have been generated by her research into the story of Picasso’s friend Carlos Casagemas and his suicide; the state of Guernica; Arabic and Jewish mothers become insane over the loss of their children; the marginalization of the assumed feebleminded ex-slave William Traylor, and more. There is a parallel in the artist’s own tendency to collapse in exhaustion at the end of her intense campaigns of research, visionary experimentation, and final assembly of works, which she accomplishes in the small living room of her apartment in Harlem.

Grant has developed a distinctive inter-media style. Works begin on paper and many remain there, as drawings. Otherwise they may be colored, developed on paper, and then cut and pasted to plywood panels whose graining often provides a patterned ground, simultaneously referencing Orthodox icons in reverse—the plywood functions as an iconostasis, which thrusts the “flesh,” the bodily image—forward. The panels are generally small, a restriction enforced by her studio space, then assembled to form larger wall units, whose contingent and seemingly random positioning within the overall environments repeat the tactics of her Random Select theory.

PART II

Grant approaches the Drawing Room’s ungainly proportions almost as a chapel. On the sky lighted gallery wall is an assembly of four panels totaling 6 by 16 feet that read like an altarpiece, bringing together the images of the show, Crowning the Lion and the Lamb. On an opposite wall are two groupings of 12 panels, 24 by 18 inches each, which deconstruct the images and restate them as icons or Stations of the Cross. Drawings on paper complete the ensemble on the shorter walls.

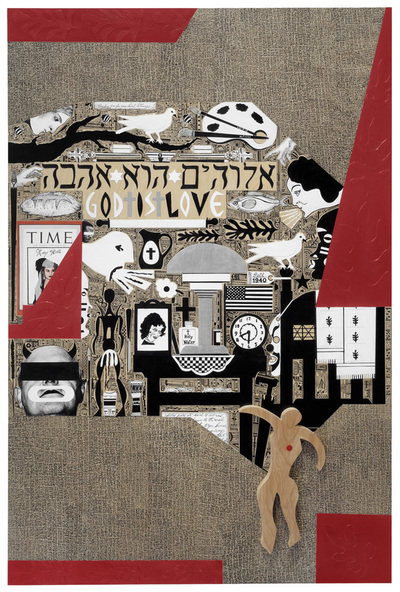

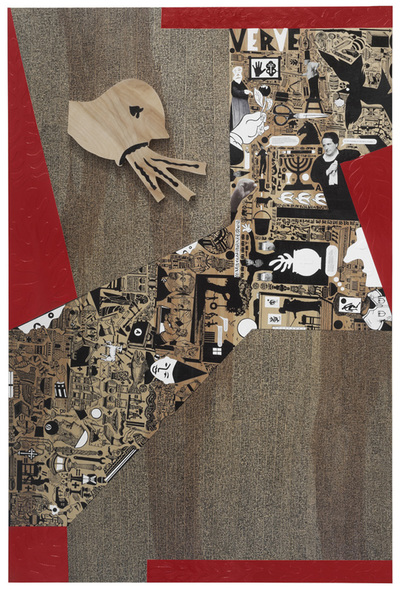

Crowning The Lion And The Lamb, 2013. Oil, acrylic, enamel and paper on birch panel, 72 x 192 x 2 inches (detail)

Crowning The Lion And The Lamb, 2013. Oil, acrylic, enamel and paper on birch panel, 72 x 192 x 2 inches (detail)

Among the new elements introduced here is a hefty New England accent, Grant’s inspiration from an amazing story she learned of through a lecture by a scholar at Yale. It concerns a woman named Mary A. Bell. Raised a devout Catholic, Bell (born 1873 in Washington D.C.) died in Boston State Hospital in 1943. Entirely self-taught as a painter, the longest service in her life seems to have been as a live-in domestic to Edward Peter Pierce, justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court and brother-in-law to the sculptor Gaston Lachaise.

Mary Bell moved to Boston in 1936 and made her life’s work of at least 140 drawings after working odd jobs, at night, during a period of three years. Bell desired fame. She wrote Carl Van Vechten, the writer, photographer and patron of the Harlem Renaissance (and closeted gay man, a contested sexuality which may be perceived as the origin of madness in many of Grant’s characters). Van Vechten bought more than 100 drawings that he bequeathed to the Beinecke Library at Yale. He also persuaded Gertrude Stein to purchase work, as well as the artist/saloniste Florine Stettheimer and the gay critic Henry McBride, whose support for modernism spanned Charles Demuth to Mark Rothko. Bell also sent some drawings to the Hollywood publicist/producer Mark Lutz, hoping to interest him in the history of African Americans.

Introducing herself to Van Vechten, Bell wrote that she had been reincarnated. Her subsequent drawings were fanciful images, frequently of beautiful Creole women and brave Ethiopian men, in settings from New Orleans, Texas, Georgia and Africa.

In an extended narrative Deborah Grant imagines Mary Bell encountering a copy of the 1930 issue of TIME magazine with Henri Matisse on its cover. Grant invented a letter based on Bell’s writing. In this identity shift she creates an outright forgery accounting for a dream that is the basis for her own current exhibition:

The letter that I received from Carl Van Vechten is very encouraging. I have been working on the drawings from the time I return home from my job. This night is different. I believe that God wants me to share my drawings with the world. I keep a box for the drawings under my bed where they are safe. I turn on my 1936 Belmont 746 Radio, it has such a rich tone. On the radio I hear the beautiful voice of Marian Anderson her voice was a rich, vibrant contralto of intrinsic beauty, I felt as if Marian Anderson was in the room with me this late night. Her voice sits deep into my soul. My eyes are not well but I will continue drawing late into the night. This Friday night will allow me to draw into the red and purple haze of early Saturday morning. I plan not to attend church tomorrow and continue working on the drawings. In the book of JOB I see I have found my light, the images flow out of me into this simple color pencil to tissue paper. I am an instrument of God.

“My lids grow heavy as I work. I know I am no match for the sandman who taunts me. I decided to lay my head down for only a minute. But slowly I drift into deep slumber. I see a shadowy haze of a man sitting on his bed. His eyes are weak as are mine. He has a gray moustache, beard and thick glasses that reflect the strong sunlight that pours into his room. He sits there ever so deeply enveloped into what he is doing. I can see and hear the sound of scissors cutting paper, on the bed are large cut out images. With the aid of the scissors he sets about creating cut paper collages on a large scale. He maneuvers scissors through prepared sheets of paper. He stops what he is doing and turns to me and says: “The cut out is not an abdication from my painting or sculpting, I call it ‘painting with scissors.’ I feel free and liberated.” He grabs for my hand and beckons to me to come and sit on his bed. I being a lady refuse the bed and sit on a stool near him. […]

He turns to me and says, “Who and what do you do. I begin to tell him my life’s journey with the drawings that I want to share them with the world. […] I hoped that the world would lead to personal acclaim and racial uplift of my people. I wish to show the world that my drawings are the work of God and not mine, and when they see this work they see my maker and the instrument which God uses. Mary A. Bell a native of Washington D.C. born September the second at 4 o’clock on Monday morning has two natures, the lion and the lamb.

I ask the man “Dear Sir what is your name?” “Henri the lamb,” he replies. “It’s a pleasure Henri, I am Mary the lion.” I wake up with the odd feeling that God has allowed me to see a glimpse into the future. I sit up in my bed and realize that I am not in my room at 37 Greenwich Park in Boston Mass. My radio and drawings are nowhere in sight. My realization that I am institutionalized at Boston State Hospital leaves me feeling the grim reminder has me beckoning for my time I have spent drawing into the nights at 3 Greenwich. I get up and walk gingerly across the ward and I see a familiar image of a man on an old copy of TIME magazine. It reads ‘Henri Matisse Monday, October 20, 1930.’ This was “Henri the lamb” or should I say ‘Henri the lion.'”

Mary A. Bell

The prophetic nature of Bell’s dream is unassailable; Grant’s panels attest to the validity of the moment. The drawings of Jesus and the three Marys (Virgin, Magdalene, and Clopas), among others, are the most derivative from Bell’s drawings. Her Creole ladies and gentlemen are embedded in patterns and decorated with repeated motifs in their costumes that embrace ethnic cloth while maintaining distinctly European roots. Felix Fanon’s politicization of “the Creole” is given a visual substance here. Creolization describes how people reinterpret themselves through interaction with one another—an ongoing struggle.

Mary of Clopas Easter ‘s Best, 2013. Acrylic, archival ink and colored pencil on watercolor paper, 30 x 22 inches

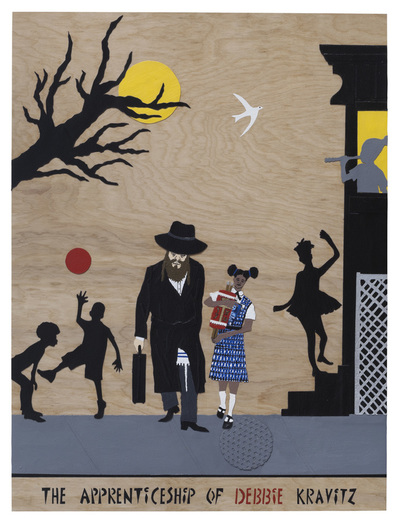

The multi-panel piece develops a concept of Creolization with reference to Jewishness. The Education of ‘Debbie’ Kravitz depicts Grant in her parochial school uniform walking through her Coney Island neighborhood alongside the beloved rabbi of her childhood—note the seagull in the sky. This recalls Grant’s birth in Toronto and her introduction by the rabbi to Mordechai Richler’s novel. Even more harrowingly, her Daniel in the Lion’s Den honors one of the last surviving Holocaust survivors, whose number is tattooed under his Mogen David. The panels constitute a single work reflecting many visionary hours. Grant herself explains in this excerpt:

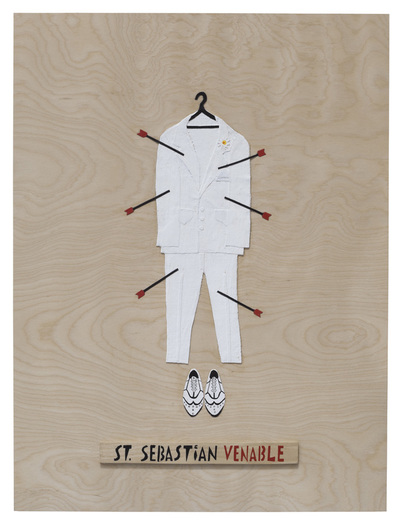

God’s Voice in The Midnight Hours is a suite of 24 birch wood panels that depicts the Judeo-Christian faith. The term Judeo-Christian has been used since 1950. It stresses the common ethical standards of Judaism and Christianity. American novelist, writer and art and literary critic John Updike calls modern art “A religion assembled from the fragments of our daily life.” In this body of work I have taken the elements of daily life and Judeo-Christian doctrine and combined them to tell the truths of past, present and future of worlds that exist in my head. I combine sources from 20th-century French writer Jean Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers to 17th-century English poet John Milton’s Paradise Lost. The suite of 24 birch panels is made with Oil, Acrylic, Linen, Wood, Color Pencil, Ink, and Watercolor Paper. They are grouped in random order in sets of 12, are spare, and each features a simple image in flat colors with captions in handwritten letters. Of all the ethnicities and cultures that I was exposed to growing up on Coney Island, New York in the 1970s it was a neighbor, a Hassidic rabbi, who fascinated me the most. He owned six magnificent Torahs, which he showed to the neighborhood children, explaining their layout using a ruler like a Yad, a Jewish ritual pointer. As an adult, I realized how unusual this experience was, and I appreciated the man’s passion for his religious heritage and his willingness to share it with non-Jews such as myself. I use these sources to tell the biblical stories told in both the Christian bible and the laws of the Hebrew Torah. The 24 birch wood panels also have individual titles. These represent different chapters that one might see in different books. I imagine myself in Library of Congress going through 32 million books and 61 million manuscripts, to simplify them down to tell my story of man.

St. Sebastian Venable God’s Voice In The Midnight Hour, 2013. Oil, acrylic, enamel, paper and linen on birch panel, 24 x 18 x 1 1/2 inches

The Apprenticeship Of Debbie Kravitz, 2013. Oil, acrylic, enamel, paper and linen on birch panel, 24 x 18 x 1 1/2 inches

Intricate surprises abound in this work. A panel with John Waters’s superstar, Divine, takes its title from Jean Genet’s 1943 debut novel which was the basis of the Baltimore drag queen’s name. Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers was written in prison, on sheets of brown paper that prison authorities provided to prisoners, with the intention that they would make paper bags. A guard discovered that Genet had been making “unauthorized” use of the paper and burned the manuscript. Undaunted, Genet rewrote. The second version survived and Genet took it with him when leaving the prison. Published with a foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre it became a fundamental text of Beat and subsequent queer culture and post-modernism. The panel exists here as validation of that, and also as a curious link to the city of Baltimore—the repository of the great holdings of Matisse works and hometown to Divine and John Waters, whose own dreams Genet sparked. Random Select, indeed.

The Drawing Room installation underscores another visionary link in the way the skylights evoke some of the flood of white light that illuminates Matisse’s chapel at Vence, 1951, acknowledged as the greatest work of religious art in modernism.

Finally, it is a move of courage and daring to accept the challenge of Updike’s popular but profound description of art as a secular religion. Rap, graffiti, orthodoxy and street religion, the determination of peripheries of exclusion of the insane and non-conforming sexualities, these are huge cultural forces. Grant’s creolization of artistic technique—neither painting nor sculpture although each element claims a third, sculptural dimension—distinguishes her visual language. She embraces the history of prior art as she roils the waters of the present.