Steve Turner is pleased to present Herida Oscura, a solo online exhibition by New York-based Carlos Martiel which features photographs that document a number of his performances over the last thirteen years. Martiel uses his body as an axis of conflict to unearth issues of race, migration, isolation, and injustice. Since 2007, he has presented ninety performances, many of which are informed by the experience of structurally oppressed and marginalized minorities throughout histories and cultures. Martiel researches these collective legacies of pain, resistance and survival to turn them into bodily rituals of self-inflicted violence and sacrifice, channeling through a visceral language his radical and candid vision of humanity’s long-standing struggle with otherness. The unapologetically blunt and poetically infused images created and embodied by the artist bear witness to the uncomfortable truths that keep shaking our societies to the core.

Carlos Martiel (born 1989, Havana) graduated from the National Academy of Fine Arts in Havana (2009). Between 2008 and 2010, he studied in the Cátedra Arte de Conducta, directed by Tania Bruguera. His works have been included in the Sharjah Biennial; Cuenca Biennial; Venice Biennale; Casablanca Biennale; Liverpool Biennial; Pontevedra Biennial and Havana Biennial as well as the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; La Tertulia Museum, Cali; Centro de Arte Contemporáneo, Quito; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Museum of Fine Arts Houston; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo del Zulia, Maracaibo; Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan, among many others. This is Martiel’s third solo exhibition with Steve Turner.

I remain hands and feet tied by a flag of the United States.

I lay beneath seven layers of rocks and dirt taken from different neighborhoods of Los Angeles where people have been killed by the police.

I am detained against a wall behind a barbed wire which creates a seclusion space inside the gallery that people can enter to closely observe my body.

In Ecuador, homosexuality was considered a crime with a prison sentence of up to 8 years. It was not until 1997 that Article 516 of the Penal Code criminalizing homosexuality was considered unconstitutional.

Nowadays in Ecuador there are Gay Conversion clinics with treatments and practices that are illegal. According to the testimonies and complaints of young people who have been forcibly interned at these places: people have been subjected to involuntarily seclusion and isolation, physical and psychological torture, humiliation, deprivation of sleep and food, as well as “corrective rapes.” In the legal sense homosexuals have stopped being considered criminals in Ecuador to become sick subjects to be treated.

I remain standing barefoot on a sculpture that has the shape of the map of the USA, made with Anti-climb security fence spikes.

This performance is thought from the context of the immigration crisis in USA, which has intensified and exacerbated after the election of Donald Trump. Intruder (America), reflects on the immigration policies that have restricted access to immigrants and asylum seekers in the USA, as well as the xenophobia and hostility that many immigrant groups face today inside immigration detention centers.

9 diamonds were inserted into my skin in different parts of my body. A white American man removes them and places them inside a box, which he takes with him once he finishes extracting them. I remain lying down for several minutes with the open wounds.

During the opening of the exhibition, my sedated body remains lying on a tire tube.

How many did not make it? Will we ever know the number of those who perished in that tragedy? Will we know how many Cubans have died in the strait that separates Cuba from the United States in over half a century? Sunk beneath the stream in the short stretch of the Gulf lays one of the largest cemeteries, filled with victims of hate and tyrannical pride. Death finds them in civilian boats attacked by ships and fighter jets, in rafts built on desperation, in a nightmarish shipwreck, swallowed by storms and burned by the sun.

– Ernesto Santana

I kneel in the lower level of a metal and glass structure inspired by the design of the ancient hourglass. The upper level is filled with water from the Mediterranean Sea, which gradually seeps through an orifice until I am submerged.

I stand in the center of a dark room with 125 stars sewn around my body. The stars were cut out from all the flags that contain this symbol within the American continent and the Caribbean (Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Granada, Honduras, Dominica, Panama, Puerto Rico, United States, Venezuela, St. Kitts & Nevis, Paraguay, Costa Rica, Curacao, French Guiana, Saba, and Suriname). Every time a person enters the space, a motion sensor turns on several black lights that highlight the stars amidst the darkness.

I stood in the middle of a space with the five points of the twelve stars of the European flag sewn onto my chest and arms. After a while, a person severed and removed the stars from my body, then I left the space.

I stand in the living room of the house where I grew up. A pest-control worker from the Cuban government’s vector control campaign fumigates the house with the pesticide used to eradicate the Aedes Aegypti mosquito. I remain in the space throughout the whole process until the toxic fumes dissipate completely.

An individual wearing military boots keeps his foot on my head impeding me to lift it.

I lay in fetal position with my body covered of human blood, donated by immigrants from Mexico, Estonia, Italy, Venezuela, England, South Korea, as well as the United States.

I lie in a block of crushed ice and I stay until the need to increase my body temperature makes me leave the place.

A Uruguayan descendant of Charrúa agrees to have the silhouette of his body sculpted in one of the walls of the museum by means of a chisel and a hammer. The debris removed is used to cover my body.

When the Spaniards arrived at Río de la Plata in the 16th century, the Charrúas already occupied the area to the north and south of the Río Negro as well as the area approaching the Atlantic coast in what is now known as the Department of Rocha within the current Uruguayan territory. In 1831, the Charrúa population was drastically reduced because of an attack led by Fructuoso Rivera, who organized an army to expropriate the lands in which the Charrúas moved freely. This historical event is known as the slaughter of Salsipuedes, in which more than 40 Charrúas were killed and another 300 were captured and sent to the capital of the country in a forced march. Most of the prisoners, mainly women and children, were sent to Montevideo where they were subsequently separated, enslaved, and Christianized. Four adults were sent to France and exhibited to the public as exotic specimens and soon died thereafter. This work reflects on the historical void in the collective ancestral memory of Uruguayans today. It also reflects on the ethnocide and violence perpetrated by the Government against the Charrúas, making them invisible, subjecting them to discrimination, and depriving them of their fundamental rights. To this day, they continue to fight despite the endured systemic oppression.

I lie for two hours within a block of clay while drops of water fall near my mouth from the ceiling.

This piece reflects on the significant challenges faced by the immigrant community in California and the United States at large. Challenges that, generated by lack of immigration status along with low quality of education and limited English proficiency, reduce their opportunities for social mobility and access to a better quality of life.

Two catheters are placed in my forearms to allow the blood to flow and blend with the seawater.

I stand on a sculpture shaped as a wheel. Three Europeans of different nationalities take turns using a hammer beating the sculpture until it is reduced to debris.

The Rromani people, or more commonly known now as “Rromà”, are an ethnic minority in Europe. Some theories suggest that they arrived to European territory through two large migrations. According to the linguist Vanya de Gila-Kochanowski, in the ninth century, Muslims invaded India and the Indians living in the northwest territories of the Hindustani peninsula began a large migration westward. The second migration occurred in the thirteenth century, when the people now self-identified as Rromà left their homes after the Mongol armies arrived and finally conquered the territory. From then on, the exodus of these travelers has been continuous.

The Rromà people have suffered countless violations of their human rights, such as slavery, repression, and political persecution. Nowadays, some of the main challenges facing this community are the social stigmatization that makes them victims of xenophobia, racism, poverty, and exclusion from the labor market.

This work was conceived from the elements and colors that make up the Rromani flag.

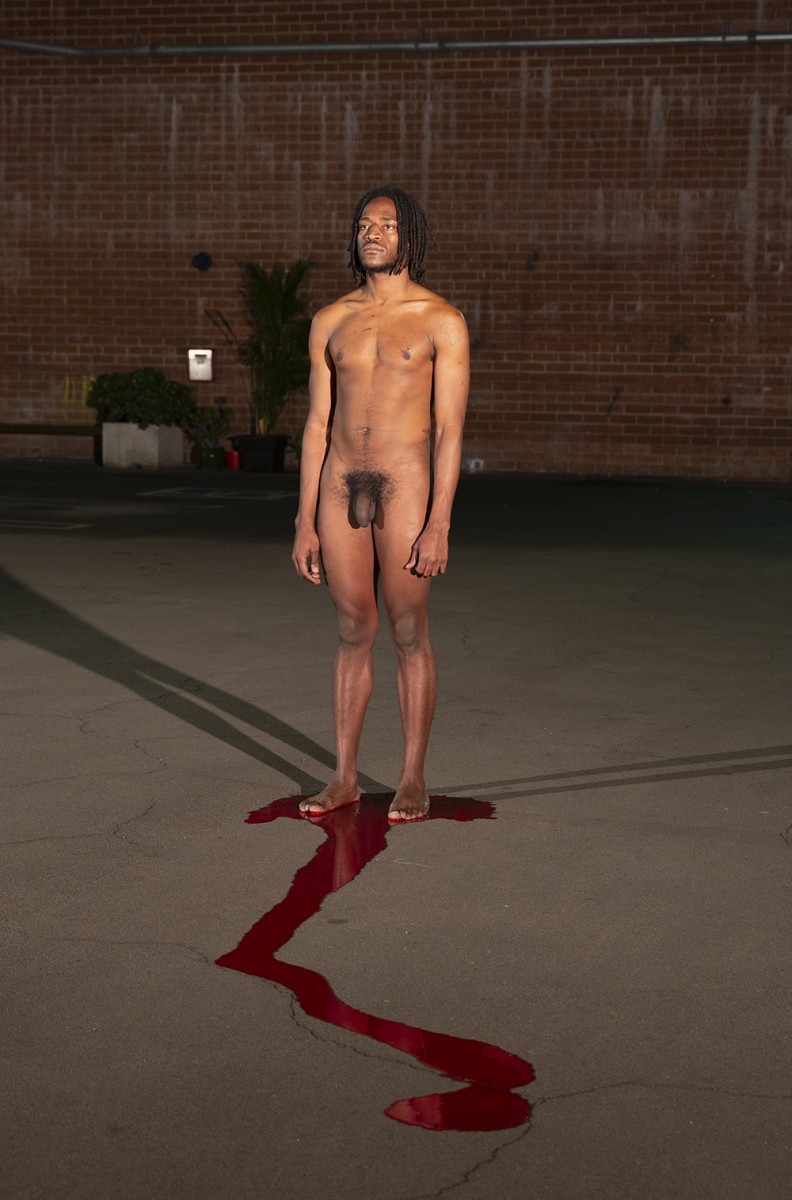

I stand on a puddle of my own blood.

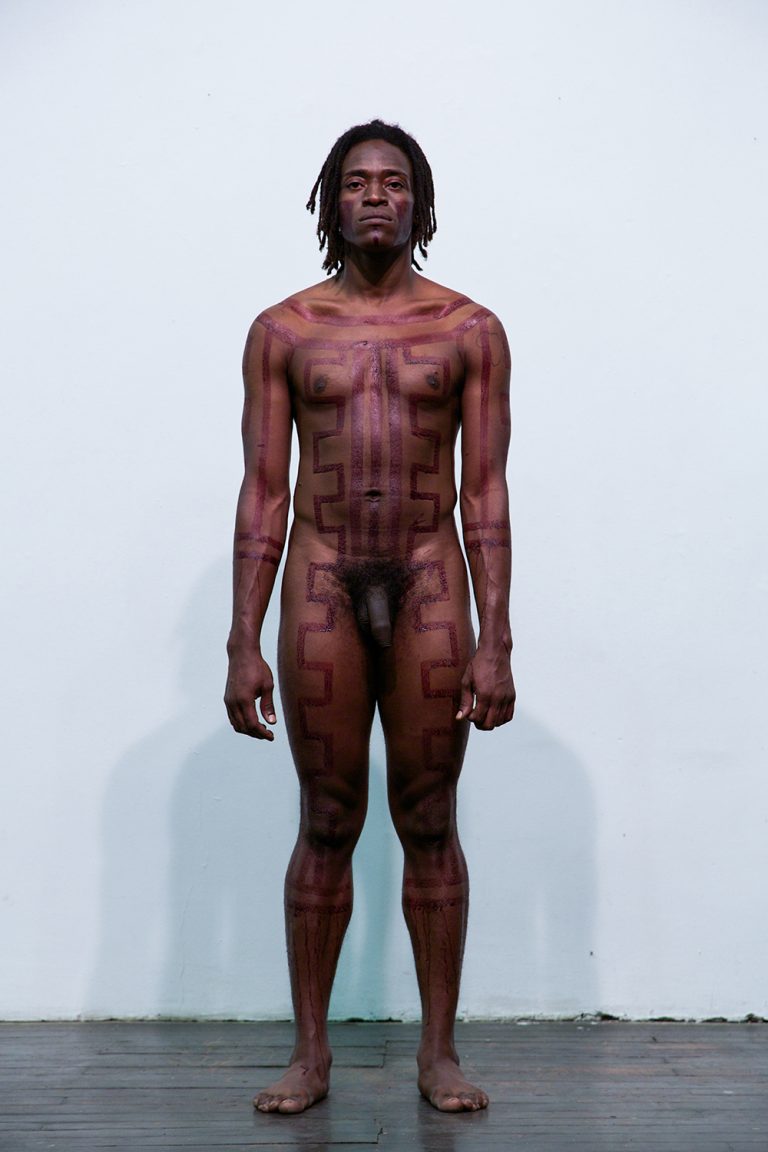

Kayapó body painting done on my body with human blood by an indigenous person.

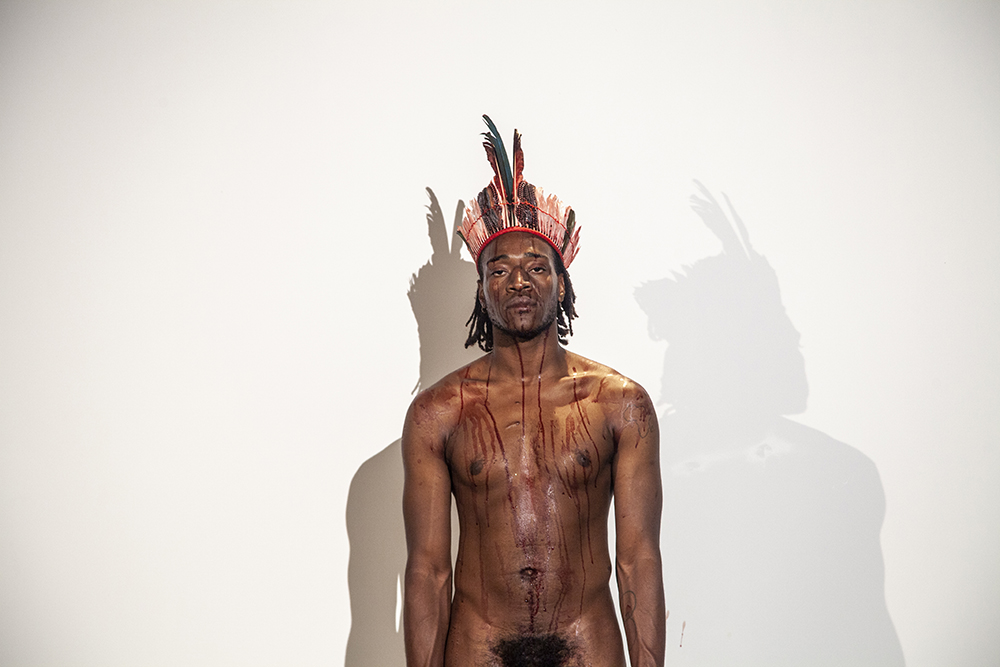

I stand in the gallery carrying a Guaraní Kaiowá headdress covered in human blood.

A history of racism, expulsions, and collective suicides dating back to colonial times has marked and reduced the Guaraní population in Brazil. After the war with Paraguay ended in 1870, the Government of Brazil began to sell land, trampling on the rights of the native populations who lived and still live there. With the passage of time, the situation of the Guaraní and other indigenous peoples of Brazil has worsened, since they have been evicted from their lands and massacred by gunmen in the service of agribusiness. In spite of this, the peaceful struggle for the rights and the demarcation of the territory of these ancestral populations still stands.

I lay on the ground with pigeon feathers, brought to the U.S. from Cuba, inserted into my arms.

I enter the sea and take a rock, I hold it over my shoulders for one hour.

I lay on the floor of the gallery with my left foot caught in a steel trap used to hunt wild animals.

I’m lying down in a fetal position with a hunting arrow crossing my waist.

I am restrained under the weight of a wooden cross which functions as a pillory.

I remained standing for two hours with the collar of a blue shirt stitched to the skin around my neck.

“Blue-collar worker” is a term used to refer to a working class person who performs manual labor.

This performance was realized on May 1st, International Workers’ Day. This holiday is celebrated in most of the world, but not in the USA.

I place on my chest all the medals awarded by the Cuban State to my father for his patriotic merits.

I lying down in a fetal position with a small American flag inserted on my shoulder.

Please direct inquiries to:

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la