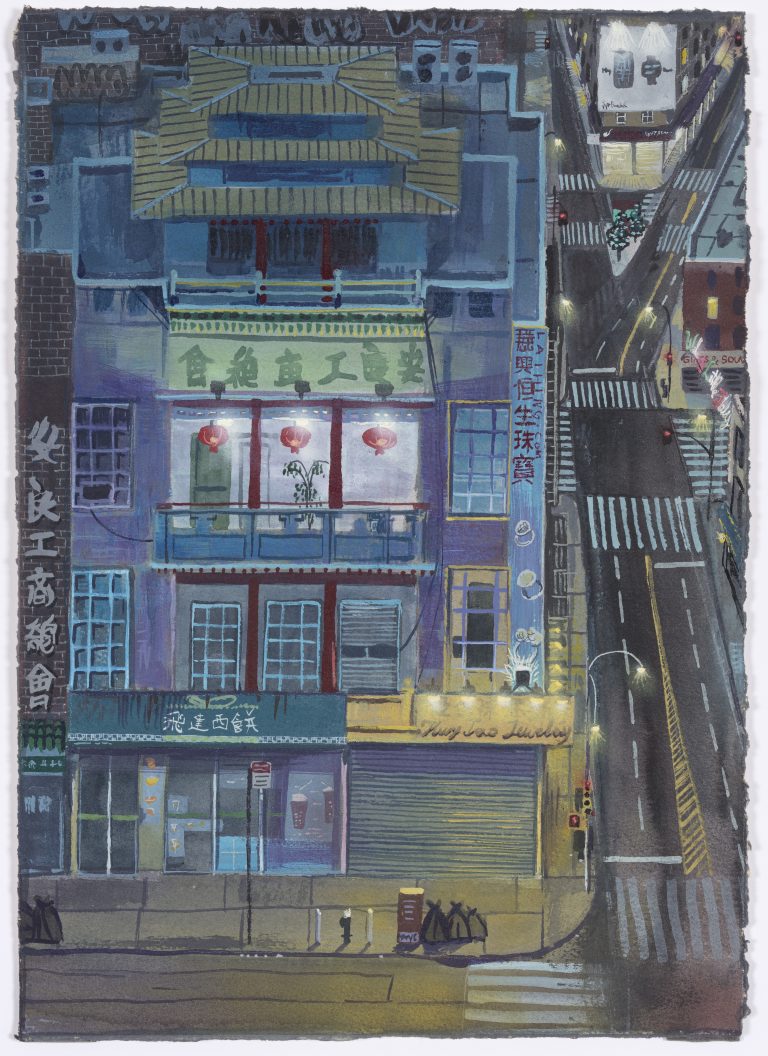

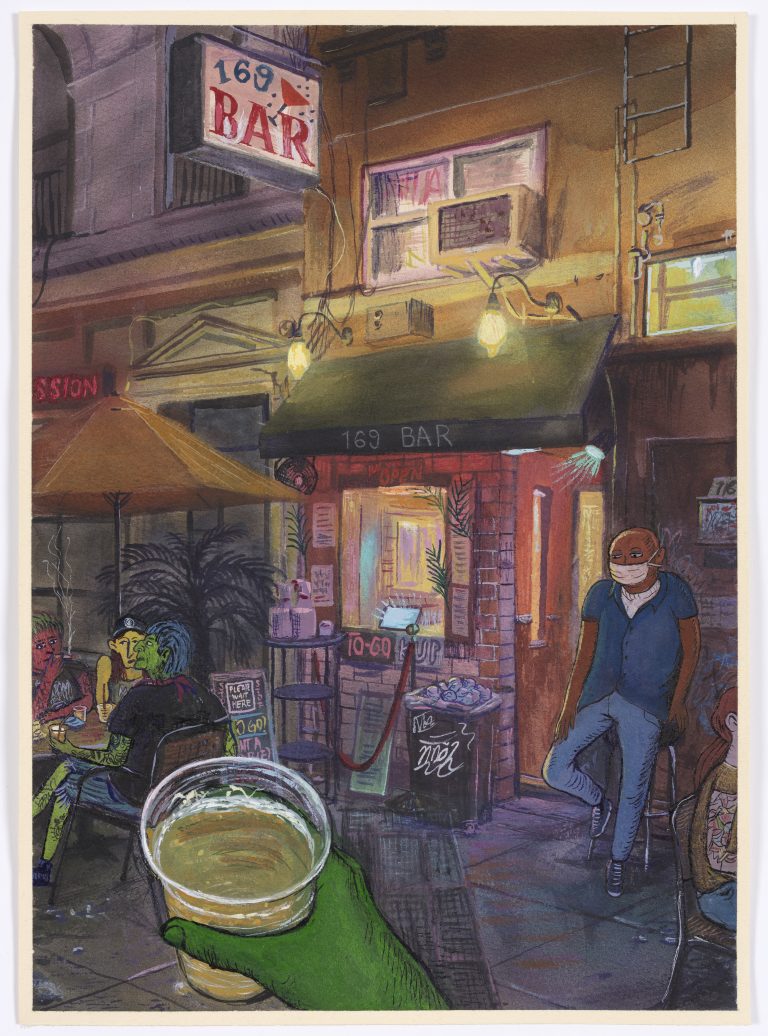

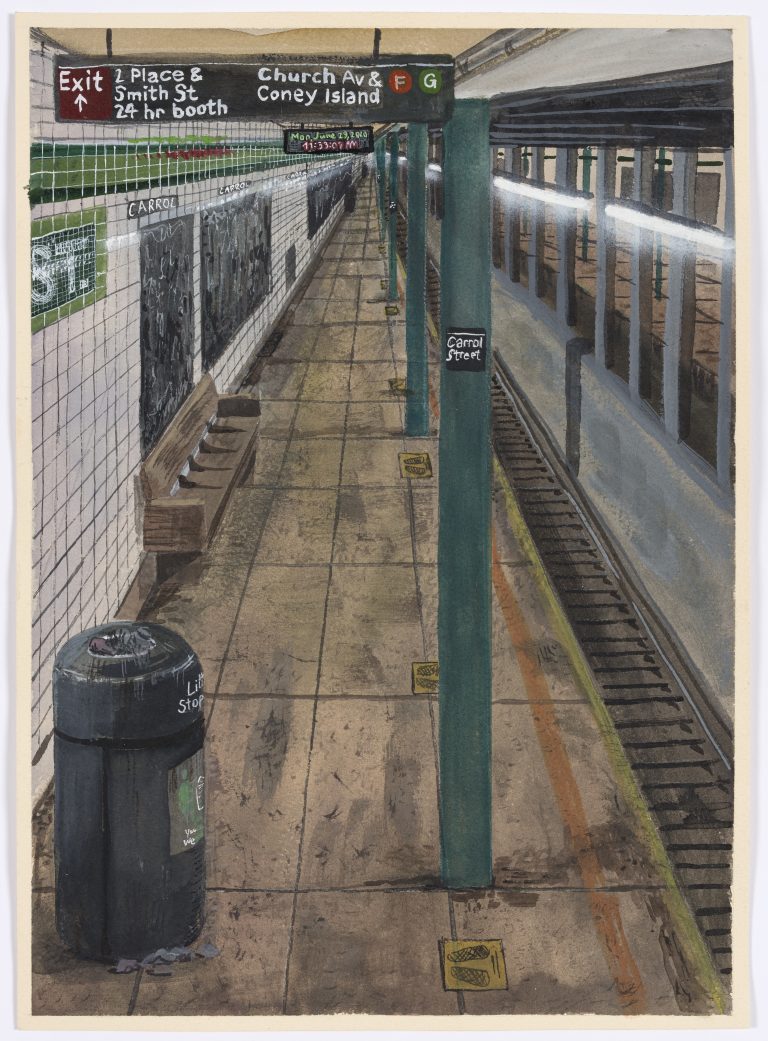

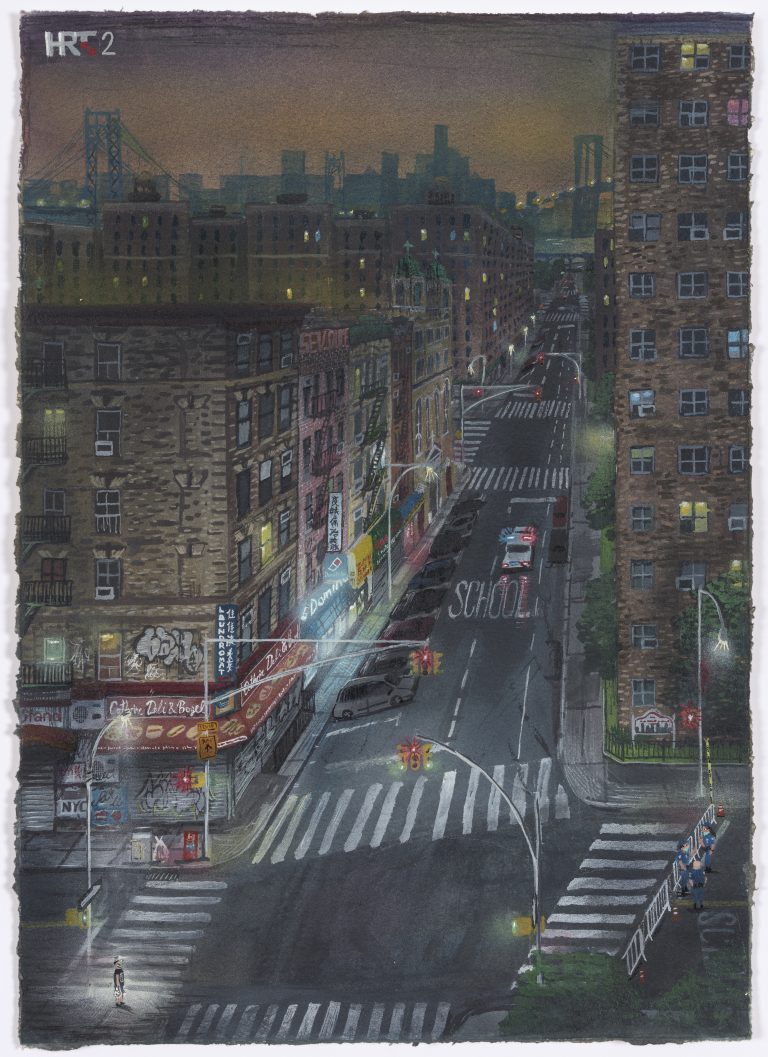

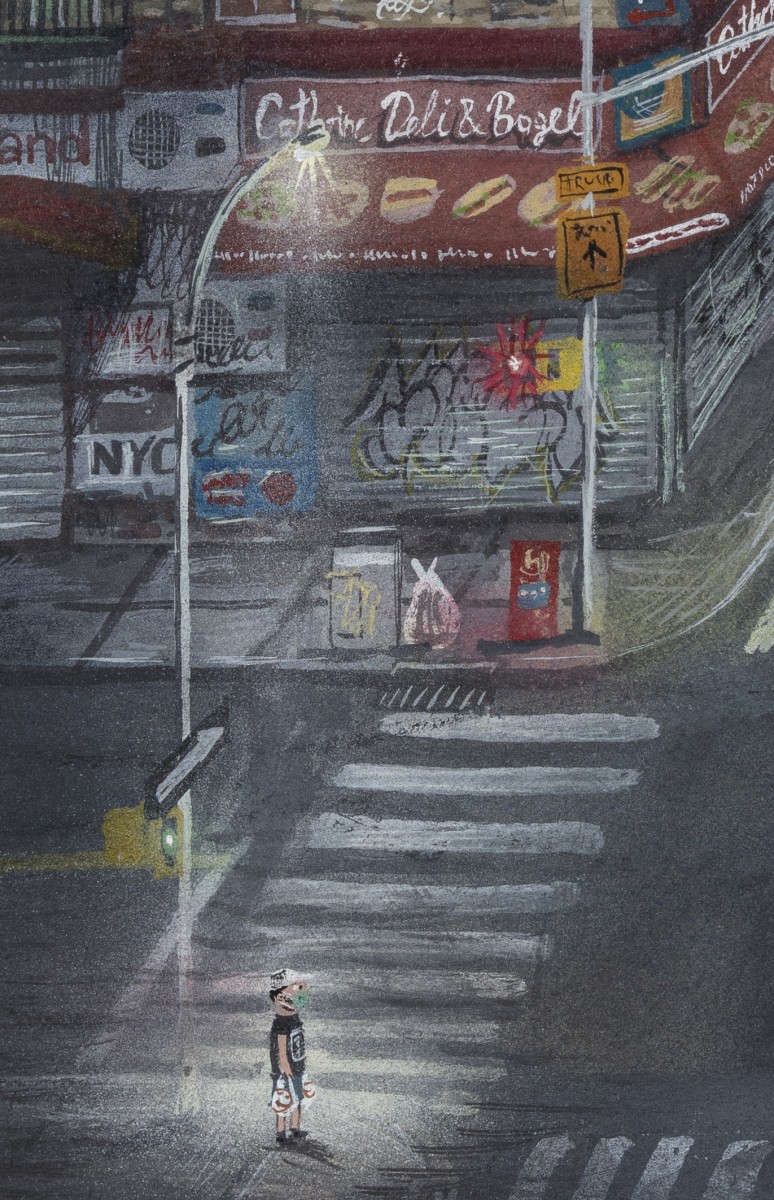

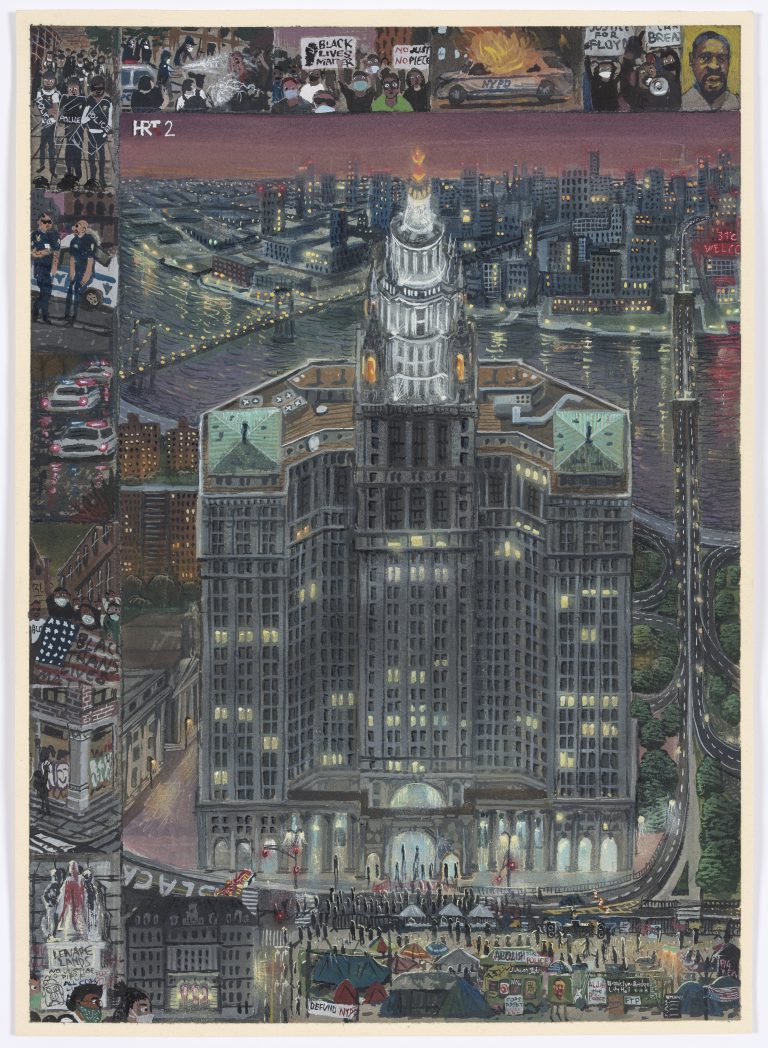

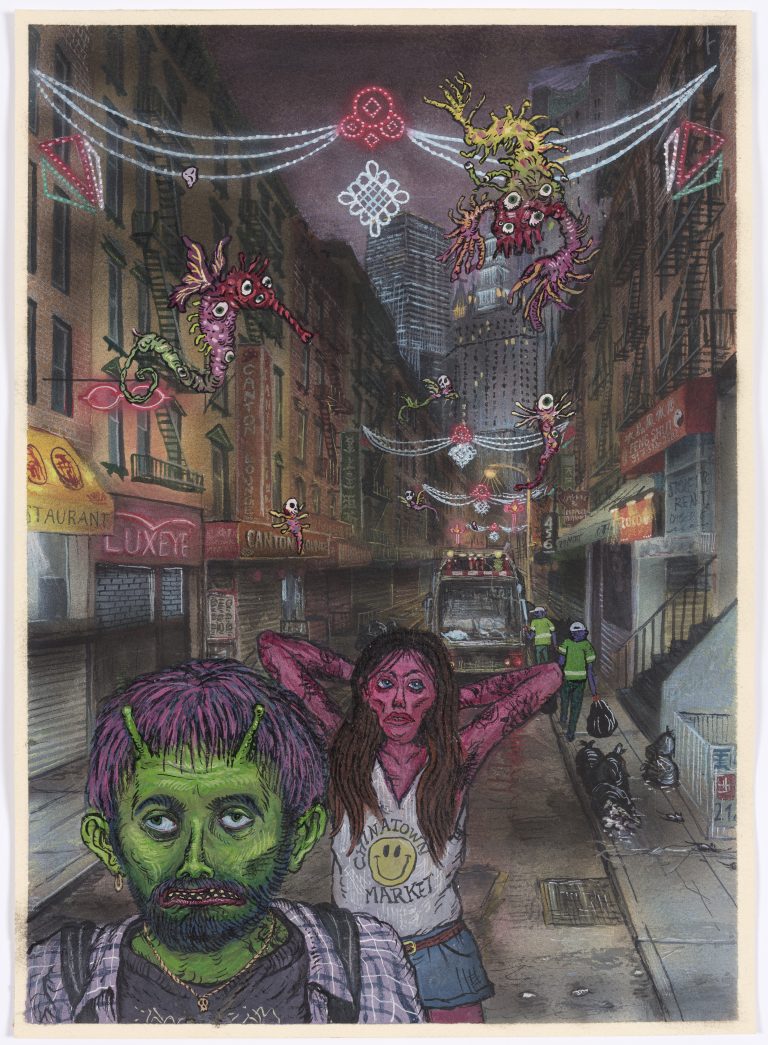

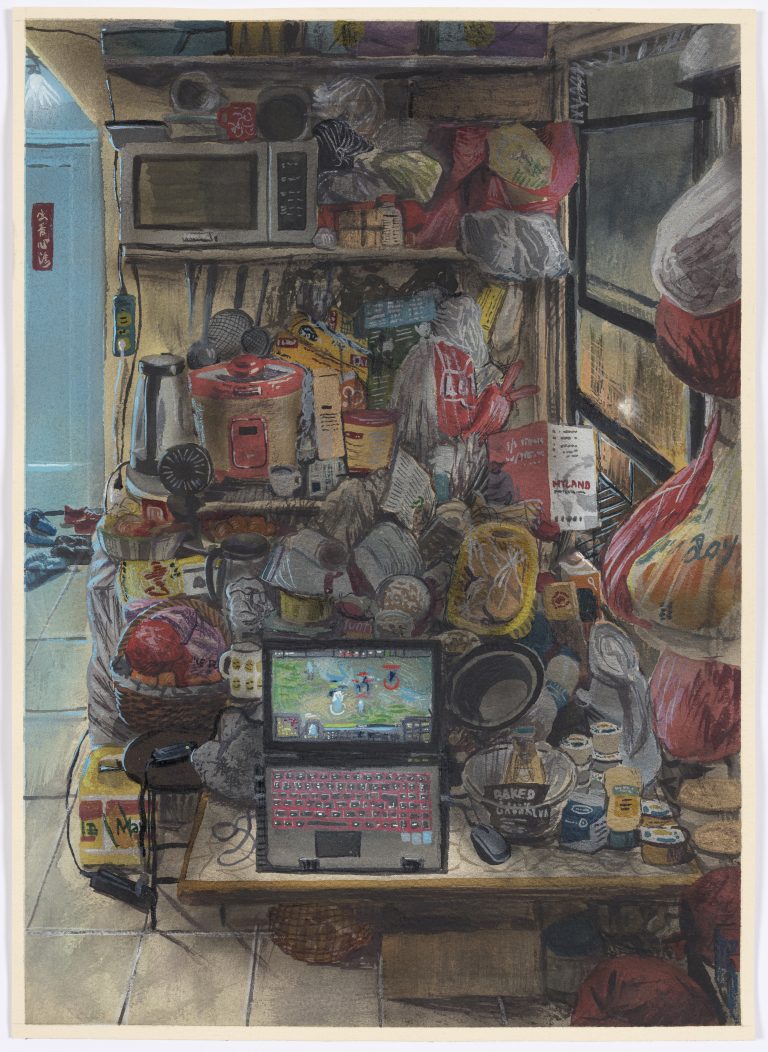

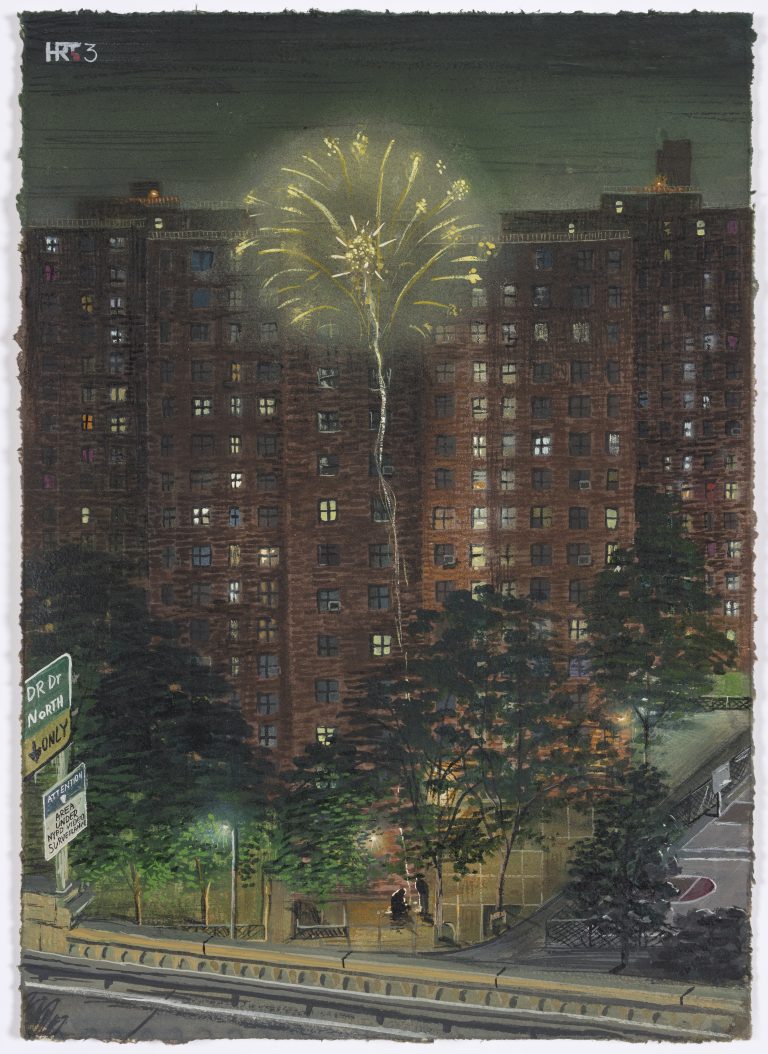

City Lights by New York-based Stipan Tadić features paintings of New York that he created during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Tadić has explored the city at night, observing, drawing and writing down his observations. He found Chinatown to be of special interest. Even though it is an enduring symbol of the city, more of its essence was revealed in the absence of crowds. While the works were intended to document an historic moment in the city, they also came to serve as a psychological diary for the Croatian-born Tadić, who observed a new form of dystopia in New York’s empty streets. Colorful neon signs were flashing but no one was there to see them.

Stipan Tadić (born 1986, Zagreb, Croatia), earned an MA in painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (2011) and an MFA from Columbia University (2020). His first solo exhibition was in Zagreb in 2009 and since then he has had numerous solo and group exhibitions. His work was recently included in Alone Together, a group show that featured work by twenty-three members of the celebrated Columbia University MFA Class of 2020. This is Tadić’s first solo exhibition with Steve Turner.

Stipan Tadić in conversation with Steve Turner

Turner

Congratulations for earning your MFA at Columbia during these challenging times. Before we talk about your experiences in New York, let’s go back in time. Where did you grow up and go to school? What are some of the biggest influences from your past?

Tadić

Thank you Steve, it is such a relief to be out of school, again. I was born in Zagreb, Croatia, but soon moved with my family to Salzburg, Austria where I lived until I was eleven years old. We moved back to Zagreb where I went to high school and college. The way I look at my past always changes, depending on what I think about at the moment, but I think having spent the nineties in Austria and having had my formative years in a German speaking country was very significant. My elementary school in Salzburg was something of a music school, I learned how to read scores, play instruments and sing. I became fascinated with Austrian and German pop culture of the period and remember watching The Love Parade on live television and being fascinated by the rave culture. I will never forget that. And like many kids, I used to play a lot of video games and was obsessed with cartoons.

Turner

Can you give some context on Croatia? What was it like growing up as a foreigner in Austria? Did you feel like you were in exile? What was life like for your family?

Tadić

When my family left Zagreb for Salzburg, Croatia was part of Yugoslavia. My father found a job working in a printing company. At first my mother stayed home to take care of me and my younger brother and sister. Later she got a job in a supermarket. By the time I was five years old the war in Yugoslavia broke out and we couldn’t go home anymore.

In Austria we were safe but there was constant discussion about Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia which I didn’t understand at first. I remember later having Serbian friends and having more awareness of the larger political movements. I also remember that I refused to allow political differences to affect my life or the way I looked at people. In retrospect, I realize that I was lucky to grow up in Austria where I learned this lesson while living among all sorts of immigrants.

I never felt like an outsider. I learned german very quickly and my early drawing and painting skills helped me a lot in school. I got along really well with the teachers and my peers. It was different for my parents, especially my mother, who struggled with the language and didn’t really like her job.

Turner

What was it like to return to Croatia?

Tadić

After the war ended we returned to Croatia. It was a time of hope. We were returning to a new country and to the idea of independence. I remember that I preferred to stay in Austria because I was going to a good school and was doing well, but I guess it was not my decision. Back in Croatia, my father started a small printing company. He would print business cards, wedding invitations, etc. My mother, brother, sister and I would work for him and it was kind of hard. Eventually my parents separated and my father’s business didn’t survive the financial crisis of the late 2000s. Today my parents are both unemployed, my mother lives in a small town on the coast, has a child and a new family, and my father is still in the suburbs of Zagreb.

Turner

Even though these moves must have been highly eventful for your family, It seems as though you were able to insulate yourself from the larger political events that drove your parents to move. Knowing how you later took to New York so easily and that learning languages is easy for you, I am thinking that you have an innate ability to adapt and to accept change. Do you agree?

Tadić

Perhaps, but I really can’t tell. I feel like I just always was protected by my drawing practice. Wherever I went I would just be doing my own thing and hanging out with people whom I thought were cool. There are good people everywhere and I feel like I always end up in good company. I have been very lucky to have very good classmates at all my schools, in primary school, high school and college.

Here in the U.S. I also found it very easy to adapt. Perhaps the big history of immigration makes my accent less strange. I really don't feel as though I am a foreigner. Wherever I am, I spend most of my time working alone in a studio. In that way, it’s all the same.

Turner

What sort of art education did you have in Zagreb? Did you learn technical skills? Art history? Conceptual art?

Tadic

I went to an art high school where I did a lot of printmaking, mostly etchings. I really liked my high school art history teacher and learned a lot very early. I was also very into live drawing. Then I went to the Academy where the education was intended to be less traditional, more oriented towards modernism and abstraction. Even though it was probably very traditional compared to education in the United States, I felt that it went too fast into contemporary art and that we would have been better off learning more historical approaches first.. So, even though the professors were pushing me into broader brushstrokes and a modernist conception of freedom, I always stuck to the thin brushes and developed this hatching style of painting. It was a kind of rebellion. Art history classes in college were pretty chaotic, but I liked them and my classmates a lot, so much so that we studied together even more outside the classroom.

Turner

Are you saying that the professors at the Academy favored abstraction and that you favored creating representational works?

Tadić

They were not necessarily favoring abstraction, but they certainly pushed us to find our own styles, or at least some version of the dominant styles of the 20th century. I was only twenty-one at that time and I was afraid I might get stuck in some copied version of one modern style or another if I followed their plan. So, I decided it was better for me to stay in the figurative realm for a while, learn how to draw and paint in a classical way and take that as my base for further development. I also sensed that there were not that many of us who drew or worked representationally. It was a very uncool thing to do so naturally I wanted to do it.

Turner

After you graduated from the Academy, it seems you had quite a few years before you enrolled in the MFA Program at Columbia. What did you do during these years?

Tadić

Yes, I was a full time artist for around ten years. I was doing a lot of shows, solo and group. I had a studio with my friends in a squat called Medika, in the center of Zagreb. We were throwing lots of parties there, organizing shows and events. It was really nice. We were part of a squatting, anarchist narrative and participated as a collective. Being part of Medika helped me to stay independent and develop my own thing. The rent of the studio was quite low and I could do whatever I wanted. I started creating murals and comics and began to participate in street art jams and got involved in the comic book scene. Today I am still publishing comics in independent zines around Europe. I did a lot of commissioned portraits for money, which was a big part of my income. I am very happy that I don’t have to do that anymore. Zagreb doesn’t have a lot of commercial galleries or an art market. It is nothing like the U. S. or other developed countries. When you do shows, they are mostly just funded by state money and if you are lucky to sell something, it probably is through your own connections. In Zagreb, one must pave their own way to survive. By comparison, I did very well there. I had a good time and developed a nice audience that likes my work and has helped me sustain my practice.

Turner:

What then made you want to go to graduate school in the United States?

Tadić:

Once I turned thirty, I felt the need to take my practice to a higher level and to learn more about theory. I thought that several graduate programs in the United States that were connected to a large university were a good choice for me. In that way, I could take graduate level classes in philosophy and art history without applying to these departments. I also got a full scholarship from Zagreb and felt really lucky to get into Columbia. In addition to the classroom curriculum that I wanted, I also hoped to get out of Croatia to see if I could develop a context for my work that was more international and New York seemed like the perfect city for that, one that could help me gain new perspectives, not only on myself and Croatia, but also on Europe.

Turner

Did you get what you wanted at Columbia?

Tadić

Yes, I am very satisfied. I took around ten academic classes, read more books over the last two years than I did during the previous ten years. I have many friends around New York, the U.S. and the world. I feel that I gained the perspectives which I sought and I feel very fortunate to have earned my MFA at Columbia.

Turner

Now, let’s turn to the works in City Lights, all of which depict post-COVID scenes in New York. You presented the first four works in this series in Alone Together, the group exhibition that we presented after you and your classmates at Columbia were locked out of your studios in March. I understand the impetus for the works that were in the group show when the quietude in New York was so striking. What motivated you to continue the series?

Tadić

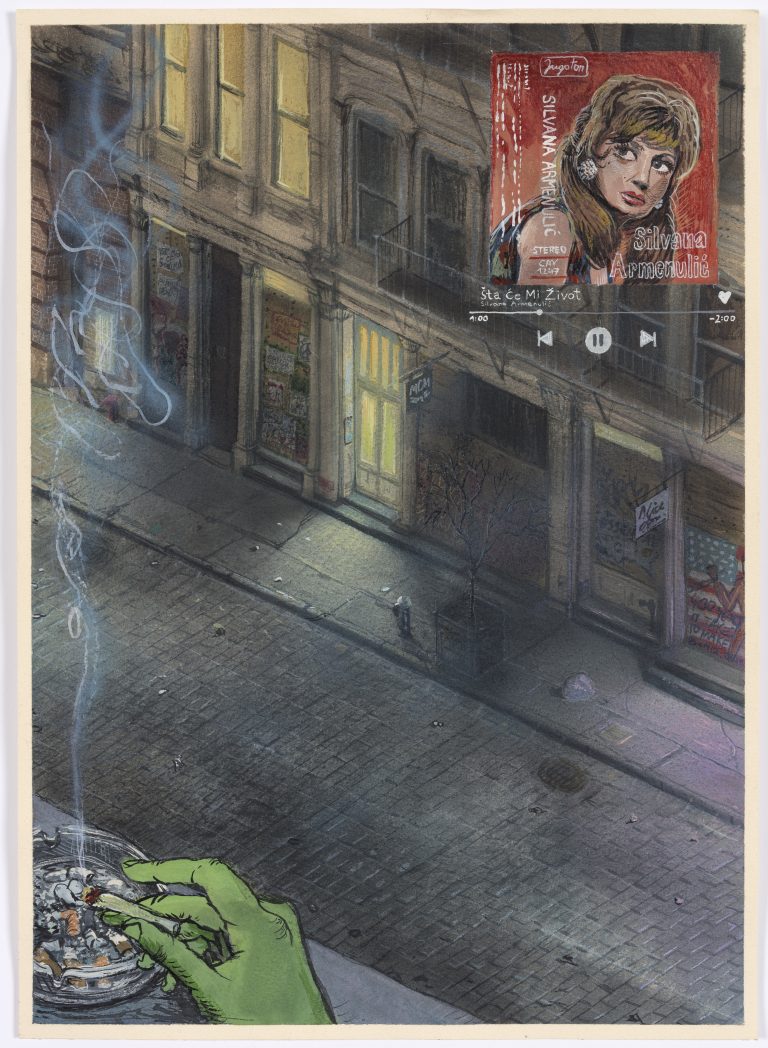

Yes, I started doing these watercolors when the lockdown started and just continued doing them until now. I guess I felt most comfortable at that time sitting at my table and doing small works on paper, trying out different angles and ways of painting. In the meantime I bought an airbrush and started working on night time cityscapes with an emphasis on lights of New York. Around the same time, I moved to Chinatown from Uptown and was really impressed by the empty streets around Little Italy and Columbus Park. The streets and the city lights without people felt so interesting. Such a simple change in the environment can produce so much meaning.

As a foreigner I felt it was important for me to document my time in New York. The series shows the route I take every day and the scenes around these areas. Working on them has helped me accept the unprecedented circumstances in which we live.

Turner

Beyond depicting New York without people, what else do these works represent to you?

Tadić

In creating a nightscape series, I was thinking a lot about the atmosphere that night represents and its symbolic meaning. Night makes me think of Japanese prints, Hieronymus Bosch, Goya and the German Expressionists, all references that I have loved since my beginning in art. My interest in the melancholy, the subconscious and underlying psychological spaces overlaps with my love of the night.

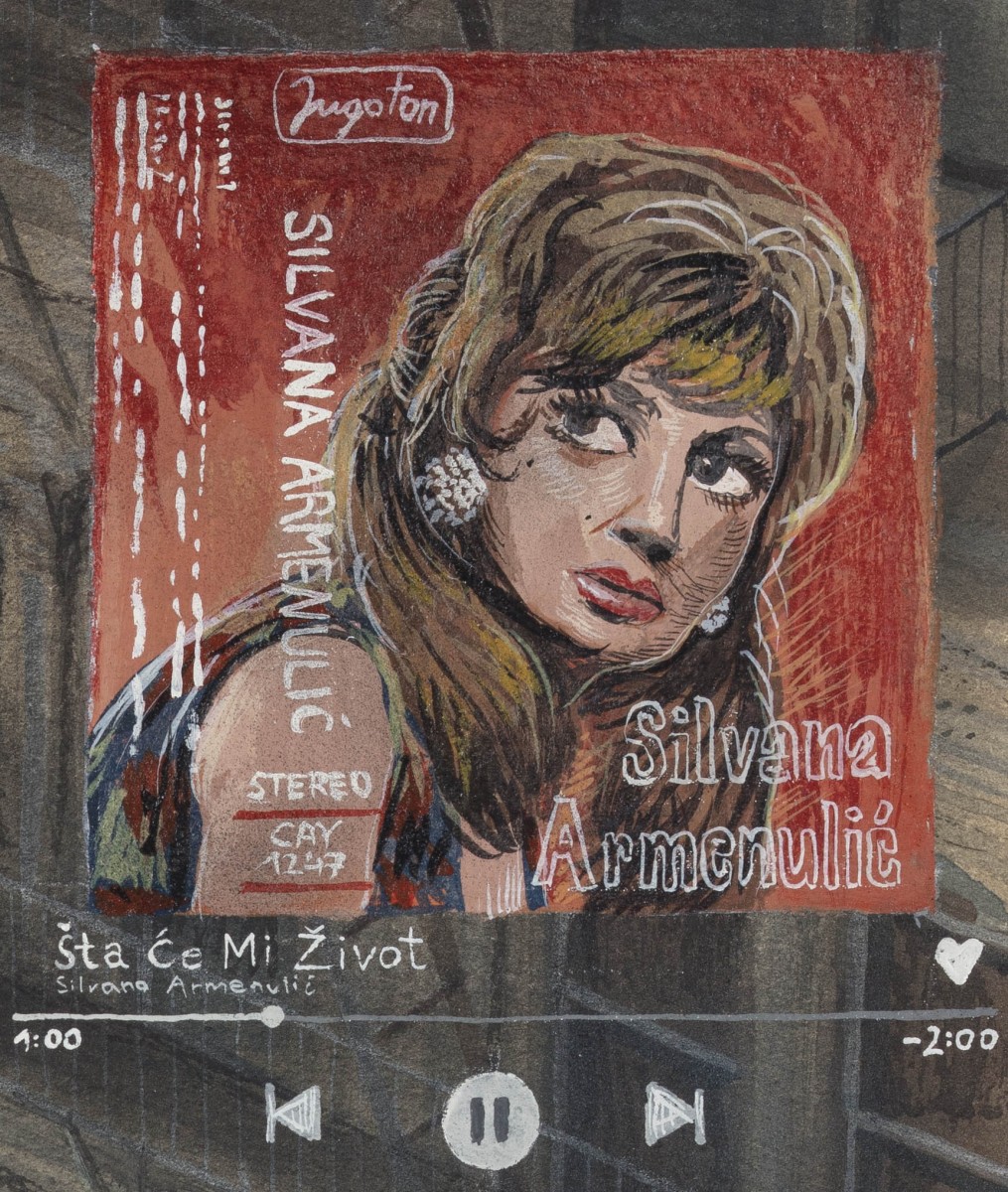

I also wanted to give the paintings a soundtrack–perhaps an Eastern European tragic melody. In one painting I juxtaposed an image of a popular and heartbreaking Serbian song from the 1970s with a scene from Soho. I wanted a collision between my inner voice and the outside world. In other paintings I included the logo of Croatian National Television in order to emphasize the Croatian filter through which the scenes are portrayed.

Turner

You wrote above as though you are just passing through New York and perhaps the U.S. Is that the case? Do you prefer living in Europe or elsewhere? Or might you be one of the newest emigre artists to settle permanently in the U.S.?

Tadić

I really don’t know where I will end up. I am looking at my options. I would love to stay longer in New York. I feel as if my context as a person from Eastern Europe is much stronger in a European context than it is in the U.S. Here I am simply a white person, but in Europe it is more clear what I represent as a Croatian. If I can’t sustain myself here from painting alone, if I must work as a bartender in order to pay my bills, I will certainly move back to Europe. Studio time is the most important thing for me.

Please direct inquiries to

steve@steveturner.la

jonathan@steveturner.la